Judy Garland sings “Memories of You” on The Judy Garland Show in 1963. The organist backing her is Count Basie:

Judy Garland sings “Memories of You” on The Judy Garland Show in 1963. The organist backing her is Count Basie:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Yes, there is an inevitable darkening, or sobering, that comes with the increasing realization that life is a tragedy, which entails, however, no need to banish gaiety. Painters know that there is nothing like black to bring out the best in other colors—the pinks and whites and oranges. It makes them dance.”

“Yes, there is an inevitable darkening, or sobering, that comes with the increasing realization that life is a tragedy, which entails, however, no need to banish gaiety. Painters know that there is nothing like black to bring out the best in other colors—the pinks and whites and oranges. It makes them dance.”

Peter De Vries, quoted in Douglas M. Davis, “An Interview with Peter De Vries” (College English, April 1967)

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review two off-Broadway revivals, Sticks and Bones and Lips Together, Teeth Apart. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

David Rabe used to be big but is now mostly forgotten save by the New Group, which revived his “Hurlyburly” in 2005 and is now giving us “Sticks and Bones,” the first installment in his quartet of plays about the Vietnam War, in which he served. You probably won’t recognize the title unless you have near-total recall, but the Public Theater produced “Sticks and Bones” off Broadway in 1971, then moved it uptown for a production that won its author a Tony, after which it was turned by CBS into a TV movie that half the network’s affiliates refused to air.

That’s quite a tale. On the other hand, “Sticks and Bones” hasn’t been seen in New York since it closed in 1972, nor have any major regional productions come to my attention. You’d expect it, then, to be a cultural artifact, as is Jason Miller’s “That Championship Season,” another anti-establishment play that rang the box-office bell but flopped when it came back to Broadway four decades later. Sure enough, it’s a leaden satire about Dave (Ben Schnetzer), a wounded soldier from a sitcom family so squeaky-clean that his father (Bill Pullman), mother (Holly Hunter) and kid brother (Raviv Ullman) are actually named Ozzie, Harriet and Rick. Blinded and broken in Vietnam, he comes home to tell them the truth about the war and finds that they just won’t listen.

That’s quite a tale. On the other hand, “Sticks and Bones” hasn’t been seen in New York since it closed in 1972, nor have any major regional productions come to my attention. You’d expect it, then, to be a cultural artifact, as is Jason Miller’s “That Championship Season,” another anti-establishment play that rang the box-office bell but flopped when it came back to Broadway four decades later. Sure enough, it’s a leaden satire about Dave (Ben Schnetzer), a wounded soldier from a sitcom family so squeaky-clean that his father (Bill Pullman), mother (Holly Hunter) and kid brother (Raviv Ullman) are actually named Ozzie, Harriet and Rick. Blinded and broken in Vietnam, he comes home to tell them the truth about the war and finds that they just won’t listen.

Merely to describe “Sticks and Bones” is to wince at its banality. The satirical frame that drives the play was already trite in 1971. Today it’s a dead metaphor…

The AIDS plays of the ‘80s and ‘90s are back. First came Larry Kramer’s “The Normal Heart,” and now it’s Second Stage’s revival of Terrence McNally’s “Lips Together, Teeth Apart,” which was originally seen Off Broadway in 1991, at the height of the epidemic. To revisit them is an undeniably interesting experience, but rarely a convincing one. In “Lips Together, Teeth Apart,” for instance, Mr. McNally flogs away at four straight suburbanites (Michael Chernus, Tracee Chimo, America Ferrera and Austin Lysy) who are spending the Fourth of July in the Fire Island summer home of a relative who recently died of AIDS. Not only are they homophobic, so much so that they won’t swim in his pool for fear of catching the dread disease, but they’re all leading lives of quiet frustration, on top of which they envy the more abundant sex lives of the gay men by whom they are surrounded. (One of the four actually kills a snake and brandishes it triumphantly, which deserves some sort of prize for neon-sign symbolism.) And yes, they undergo a group epiphany as they watch their neighbors’ fireworks and learn that Homosexuals Are Human, Too.

Whatever else this is, it isn’t art, and it doesn’t help that Mr. McNally portrays his straw men so implausibly that you wonder whether he’s ever met any straight suburbanites….

* * *

To read my review of Sticks and Bones, go here.

To read my review of Lips Together, Teeth Apart, go here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I write about a recent European Union court ruling about the “right to be forgotten,” and what it could mean to historical truth. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I write about a recent European Union court ruling about the “right to be forgotten,” and what it could mean to historical truth. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If you’re an artist, getting panned is part of life. Like the common cold, everybody gets a bad review sooner or later, and though it’s said that Lola Montez threatened to horsewhip a critic who roasted her, there’s rarely anything to be done beyond toughing it out. But Dejan Lazić thinks otherwise—and he thinks he’s got the law on his side, too.

Mr. Lazić, a Croatian pianist who lives in Amsterdam, gave a recital at the Kennedy Center four years ago that didn’t please Anne Midgette, the classical music critic of the Washington Post, who called his playing “self-conscious” and “cartoon-like” in a mixed but basically negative review. That was the end of that—until the Post received a letter from Mr. Lazić in September requesting that Ms. Midgette’s review be scrubbed from the Web. When she failed to reply, he upped the ante by claiming that it was “defamatory, offensive and mean-spirited” and thus violates his legal right to be forgotten.

Say what?

The basis for Mr. Lazić’s claim was a ruling in May by the European Union’s top court that EU citizens have a legal right to control the availability of “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant or excessive” information about them, material that would otherwise remain permanently available via Google and other search engines. Since Ms. Midgette’s 2010 review is one of the first things that comes up whenever you search Mr. Lazić’s name, he wants the Post to erase it. If they don’t oblige, he is now suggesting that he’ll officially petition Google to stop linking to the review on its European sites….

All this serves as a valuable reminder of how our existing notions of “truth” are being undermined by the migration of information from the printed page to cyberspace, which is infinitely malleable. George Orwell predicted as much when he wrote in “Nineteen Eighty-Four” of the ceaseless and insidious activities of the Ministry of Truth, one of whose functions was to alter previously published newspaper, magazine and encyclopedia articles to bring them into more perfect accord with the latest dictates of Big Brother. Any evidence to the contrary was promptly dropped down the nearest “memory hole” and whisked away to an incinerator. Today such rewriting is vastly easier: Any editor who longs to change history need only alter the electronic text of his online edition, instantly and at will. It’s carved in mush, not stone….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The 1956 film version of Nineteen Eighty-Four, directed by Michael Anderson and starring Edmond O’Brien and Michael Redgrave. The score is by Malcolm Arnold:

“Musicians’ opinions influence nothing; they simply recognize, with a certain delay but correctly, the history of music. Lay opinion influences everything—even, at times, creation. And at all times it is the pronouncements of persons who know something about music but not too much, and a bit more about what they like but still not too much, that end by creating those modes or fashions in consumption that make up the history of taste.”

“Musicians’ opinions influence nothing; they simply recognize, with a certain delay but correctly, the history of music. Lay opinion influences everything—even, at times, creation. And at all times it is the pronouncements of persons who know something about music but not too much, and a bit more about what they like but still not too much, that end by creating those modes or fashions in consumption that make up the history of taste.”

Virgil Thomson, “Taste in Music”

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, virtually all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, virtually all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Love Letters (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 1, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, reviewed here)

• On the Town (musical, G, contains double entendres that will not be intelligible to children, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• This Is Our Youth (drama, PG-13, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Indian Ink (drama, PG-13, closes Nov. 30, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY IN SPRING GREEN, WIS.:

• American Buffalo (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY ON BROADWAY:

• The Country House (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

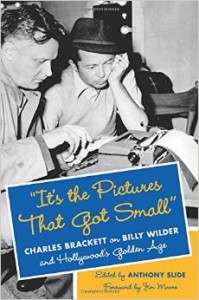

My monthly essay in the latest issue of Commentary takes as its point of departure the publication of ”It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, which will be published at the end of November by Columbia University Press:

My monthly essay in the latest issue of Commentary takes as its point of departure the publication of ”It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, which will be published at the end of November by Columbia University Press:

Of the studio-era Hollywood directors whose best films have proved to be of lasting value, Billy Wilder was the one who brought off the least likely feat: He won mass popularity by making movies that embody a dark and bitter vision of the world. Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the most impressive films Wilder made in the first part of his career, were not only financially successful but critically acclaimed as well. He was a writer, moreover, who started directing his own scripts in 1942 primarily to protect the words—a fact that set him apart from nearly all his contemporaries and helped to establish him as a key figure of Hollywood’s golden age.

The modern-day tendency to see the director of a film as its prime creative mover, however, has obscured the fact that Wilder’s scripts were invariably written with collaborators. He collaborated with the same man, Charles Brackett, on all but one of the features he co-wrote in Hollywood prior to 1951. In 1948, he went so far as to describe himself and Brackett, who produced the films that they wrote together, as “the happiest couple in Hollywood.” And yet, in that same year, Wilder unilaterally decided to dissolve their partnership and collaborate with others. He never worked with Brackett again.

Neither man publicly discussed their break save in general terms, nor did they talk with any specificity about how they wrote screenplays together. Because of this mutual reticence, and because Brackett wrote no screenplays of any consequence without Wilder, his name is now familiar only to film critics and historians.

Hence the importance of “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, a new volume of entries from his hitherto unpublished diary. In addition to relating his side of the break with Wilder and providing an exact description of the nature of their collaborative process, the book reveals that Brackett was a talented writer in his own right and a shrewd chronicler of the film industry in the 1930s and ’40s.Above all, “It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is an indispensable guide to the complex, increasingly awkward relationship between two men who had next to nothing in common and yet contrived to make a fair number of the studio system’s finest films….

Read the whole thing here.

An ArtsJournal Blog