“I am not impressed by the Ivy League establishments. Of course they graduate the best—it’s all they’ll take, leaving to others the problem of educating the country.”

“I am not impressed by the Ivy League establishments. Of course they graduate the best—it’s all they’ll take, leaving to others the problem of educating the country.”

Peter De Vries, The Vale of Laughter

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

I posted this for the first time on November 11, 2008. It’s still relevant, and (I suspect) always will be.

* * *

On October 9, 1918, an HMV sound engineer named Will Gaisberg set up a primitive piece of recording equipment immediately behind a unit of the Royal Garrison Artillery stationed outside Lille and recorded a British gas-shell bombardment. His purpose in doing so was to preserve the sounds of war before the coming armistice caused them to vanish forever from the face of the earth.

On October 9, 1918, an HMV sound engineer named Will Gaisberg set up a primitive piece of recording equipment immediately behind a unit of the Royal Garrison Artillery stationed outside Lille and recorded a British gas-shell bombardment. His purpose in doing so was to preserve the sounds of war before the coming armistice caused them to vanish forever from the face of the earth.

According to HMV’s catalogue, the recording, which was commercially released, consisted of

the actual reproduction of the screaming and whistling of the shells previous to the entry of the British troops into Lille. It is not an imitation but was recorded on the battlefront. The report of the guns and the whistling of the shells is the actual sound of the Royal Garrison Artillery in action on October 9th, 1918. No book or picture can ever visualise the reality of modern warfare just the way this record has done…it would require only the slightest imagination for one, by means of this record, to be projected into the past, and feel that he is really present on the battlefield witnessing this historic chapter of the war.

Here is Gaisberg’s own account of the making of the recording:

Gradually we came within the sound of the guns, and eventually, when only a short distance from Lille, we pulled up at a row of ruined cottages, in one of which the heavy siege battery had made its quarters. In the wrecked kitchen we unpacked our recording machines and made our preparations before getting directly behind a battery of great 4.5′ guns and 6′ howitzers, camouflaged until they looked at close quarters like giant insects. Here the machine could well catch the finer sounds of the “singing,” the “whine,” and the “scream” of the shells, as well as the terrific reports when they left the guns.

Dusk fell, and we were obliged, very reluctantly, to pack up our recording instrument and return to Boulogne–and to England; but we brought with us a true representation of the bombardment, which will have a unique place in the history of the Great War.

This recording is one of the most haunting and disturbing documents of the past that I know–one made all the more haunting by the knowledge that Gaisberg accidentally inhaled some of the gas from the attack, which damaged his lungs irreparably. In London he fell victim to the international flu epidemic that was then ravaging the city, and died on November 5, six days before World War I came to an end.

This recording is one of the most haunting and disturbing documents of the past that I know–one made all the more haunting by the knowledge that Gaisberg accidentally inhaled some of the gas from the attack, which damaged his lungs irreparably. In London he fell victim to the international flu epidemic that was then ravaging the city, and died on November 5, six days before World War I came to an end.

Today no one who served in what Woodrow Wilson called “the War to End War” is still alive. Frank Buckles, the last American veteran of World War I, died in 2011, at the age of 110. If you think of him and his comrades today–and you should–take a moment to think about Will Gaisberg as well.

* * *

HMV D378, “Actual Recording of the Gas Shell Bombardment, by the Royal Garrison Artillery (9th October, 1918), preparatory to the British Troops entering Lille”:

Ian Bostridge sings the “Agnus Dei” movement from Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem at a recording session, accompanied by Antonio Pappano and the Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia Nazionalle di Santa Cecilia. The English-language text is Wilfred Owen’s At a Cavalry Near the Ancre:

Ian Bostridge sings the “Agnus Dei” movement from Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem at a recording session, accompanied by Antonio Pappano and the Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia Nazionalle di Santa Cecilia. The English-language text is Wilfred Owen’s At a Cavalry Near the Ancre:

In a better-organized world, an artist would be able to earn inspiration. He’d get up bright and early after having gone to bed at a reasonable hour, eat a nutritious breakfast, sharpen his pencils, go out to walk the dog and help an old lady across the street, and return to his desk secure in the knowledge that the muse would descend at ten a.m. sharp. Fat chance. To be sure, regular habits are good for artists. They make it easier to be inventive on demand. But inspiration, unlike invention, won’t come when it’s called. It’s a cat, not a dog….

Read the whole thing here.

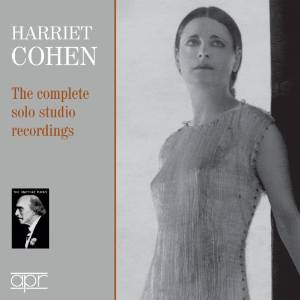

![Cohen-Harriet-02[1918]](https://www.artsjournal.com/aboutlastnight/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Cohen-Harriet-021918.jpg) I’ve been reading a biography of Harriet Cohen, one of the more interesting minor figures in twentieth-century English music. Born in 1895, Cohen is now best remembered (if at all) as the mistress of Arnold Bax, a second-tier English composer whom she met when she was seventeen and with whom she embarked two years later on an affair that lasted until his death in 1953. Along the way she tore a wide swath among his friends and contemporaries, luring Arnold Bennett and H.G. Wells, among many, many others, into her generous bed. Nor were her amorous proclivities any kind of secret. Far from it: D.H. Lawrence and Rebecca West both wrote novels in which Cohen figures, lightly disguised and easily recognizable, as a character.

I’ve been reading a biography of Harriet Cohen, one of the more interesting minor figures in twentieth-century English music. Born in 1895, Cohen is now best remembered (if at all) as the mistress of Arnold Bax, a second-tier English composer whom she met when she was seventeen and with whom she embarked two years later on an affair that lasted until his death in 1953. Along the way she tore a wide swath among his friends and contemporaries, luring Arnold Bennett and H.G. Wells, among many, many others, into her generous bed. Nor were her amorous proclivities any kind of secret. Far from it: D.H. Lawrence and Rebecca West both wrote novels in which Cohen figures, lightly disguised and easily recognizable, as a character.

In addition to being sexually available, itself no small distinction in Edwardian times, Cohen played Bach’s music with great individuality. She also programmed the works of Bartók, Elgar, Falla, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Walton, and (of course) Bax, doing so at a time when concert pianists typically steered clear of modern music. Fortunately, she made enough commercial recordings to leave no doubt of her quality, and they have lately been reissued on CD to impressive effect. She also published a memoir that is rather more truthful than one might expect, considering.

One of the things that I find most noteworthy about Cohen is that she was utterly humorless. Sensitive and intelligent, yes, and even, up to a point, perceptive. Yet her letters, to Bax and others, contain ample proof of her inability to find anything amusing, least of all herself—which, needless to say, makes some of them madly funny. Granted that love letters tend as a genre to be po-faced, I still find it impossible not to giggle at, say, this particular example, sent to Bax in 1924:

One of the things that I find most noteworthy about Cohen is that she was utterly humorless. Sensitive and intelligent, yes, and even, up to a point, perceptive. Yet her letters, to Bax and others, contain ample proof of her inability to find anything amusing, least of all herself—which, needless to say, makes some of them madly funny. Granted that love letters tend as a genre to be po-faced, I still find it impossible not to giggle at, say, this particular example, sent to Bax in 1924:

I hope you keep my letters young man! Think of the romantic reading our epistles will give young and ardent music lovers when we are dead! In 60 years[’] time their children’s children will be reading how Arnold thought Tania’s breasts the loveliest thing in the world—and she his dark rose and princess.

Cohen liked to refer to herself as “Tania” and to be so called by her lovers, a touch that strikes me as providing still more proof of her humorlessness, a fact to which Arnold Bennett, who was himself a trifle deficient in the funny-bone department, testified in this 1927 letter: “Sweet Tania, you are perfect, except for one detail: an imperfect sense of humour. However in the end you usually do see the point of a jest.”

My guess, for what it’s worth, is that Cohen’s unswerving earnestness had more than a little bit to do with her lifelong success in the sack, though it didn’t work with everybody. William Walton, who had both a strong sense of the absurd and a reciprocally impressive track record with the opposite sex, once vouchsafed this example of her seduction techniques to his wife, and while Walton was never above embellishing a good tale, this one has the ring of truth:

My guess, for what it’s worth, is that Cohen’s unswerving earnestness had more than a little bit to do with her lifelong success in the sack, though it didn’t work with everybody. William Walton, who had both a strong sense of the absurd and a reciprocally impressive track record with the opposite sex, once vouchsafed this example of her seduction techniques to his wife, and while Walton was never above embellishing a good tale, this one has the ring of truth:

It amused William to tell me that she had once played [his] Sinfonia Concertante, and then invited him back to her home for a drink. While William was sipping a glass of whisky, she had changed into a chiffon garment and asked William to hold on to a corner of the material. She then glided away, turning while walkng until the chiffon had unwound and she stood stark naked. William couldn’t stop laughing; la Cohen was very cross.

I myself have scarcely ever been attracted to such creatures, but on a couple of occasions in the long-distant past I was briefly drawn to “solemn owls” (the phrase is Patrick O’Brian’s) who were self-evidently incapable of appreciating the absurdities of human nature, starting with their own. While I always came to my senses before jumping off the cliff, there are plenty of other men who take themselves so seriously that they long above all things to be involved with women who do the same. Such folk deserve one another, and usually manage to pair off with spectacular efficiency.

In dark moments I sometimes catch myself thinking that humorlessness might actually be a prerequisite for worldly success. It’s been my experience that the humorless tend to do very well for themselves. Be that as it may, I can’t bear to be around them, or to experience their art (should they happen to be creative artists) in anything other than small doses.

Not long after 9/11, I wrote an essay about art in wartime in which I had occasion to make the following comparison:

Would that such exercises in timeliness were a mere aberration caused by the intense feelings of the moment. Alas, they have always been with us, especially in wartime and most especially in America, far too many of whose well-meaning citizens are allergic to the exhilarating fizz of high art with a light touch. It seems not to occur to them that life is such an indissoluble mixture of heartbreak and absurdity that it might be more truly portrayed through the refracting lens of comedy. Instead, they prefer what Lord Byron, who knew a thing or two about both life and art, would have crisply dismissed as “sermons and soda-water.”

Without getting bogged down in the French-German dichotomy beloved of facile writers on a tight deadline, I think the culprit-in-chief here could well be Richard Wagner, the only man ever to have written a five-hour-long comic opera. German art has always tended to be earnest to a fault, not least at the noontide of romanticism, but Wagner suffered more acutely than any of his contemporaries from the messianic delusion that art—his art—could redeem the world. Compare Mein Leben, his comprehensively unfunny autobiography, with the champagne-like Memoirs of Hector Berlioz, the most French (and Byronic) of composers, and you will see at once the difference between the seriousness of a world-saver and the seriousness of a melancholic wit who viewed both the world and himself with the same wry detachment. It is no coincidence that Wagner has always been far more popular than Berlioz: he never makes the fatal mistake of inspiring us to laugh at ourselves.

While I can’t imagine that Harriet Cohen would have read that essay with anything other than puzzlement, if not active disgust, it still makes me sad to report that in the end, the laugh was on her. Arnold Bax left his wife for Cohen in 1918, but she declined to give him a divorce. Bax told Cohen that it was because his wife was Catholic, and Cohen continued to sleep with him, hoping against hope that she would someday become the second Mrs. Bax. But after the first and only Mrs. Bax finally got around to dying in 1946, it emerged that her husband had been lying to Cohen about her being Catholic—and, worse yet, had been keeping a second mistress on the side for the preceding twenty years. Two weeks after Cohen learned about Mistress No. 2, she suffered a household “accident” that severed a tendon in her right wrist and ended her performing career. She died in 1967 and is now forgotten save by footnote hounds and collectors of old records.

While I can’t imagine that Harriet Cohen would have read that essay with anything other than puzzlement, if not active disgust, it still makes me sad to report that in the end, the laugh was on her. Arnold Bax left his wife for Cohen in 1918, but she declined to give him a divorce. Bax told Cohen that it was because his wife was Catholic, and Cohen continued to sleep with him, hoping against hope that she would someday become the second Mrs. Bax. But after the first and only Mrs. Bax finally got around to dying in 1946, it emerged that her husband had been lying to Cohen about her being Catholic—and, worse yet, had been keeping a second mistress on the side for the preceding twenty years. Two weeks after Cohen learned about Mistress No. 2, she suffered a household “accident” that severed a tendon in her right wrist and ended her performing career. She died in 1967 and is now forgotten save by footnote hounds and collectors of old records.

If Cohen’s story has a moral, I’m at a loss to say what it is. I suppose Nietzsche came as close as anyone: “Perhaps I know best why it is man alone who laughs—he alone suffers so deeply that he had to invent laughter.” Somehow, though, I doubt that Harriet Cohen did very much laughing at any point in her long and eventful life, nor do I suppose that she knew what she was missing, any more than a color-blind person has the slightest notion of what blue looks like. More often than not, they get along without it very well. Me, I’d rather be deaf than humorless—but what do I know?

* * *

Harriet Cohen and the Stratton Quartet play Elgar’s Piano Quintet, recorded in 1933:

An ArtsJournal Blog