“Those whom fate has dealt hard knocks remain vulnerable for ever afterwards.”

“Those whom fate has dealt hard knocks remain vulnerable for ever afterwards.”

Stefan Zweig, Beware of Pity

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

This is a kinescope of an episode of I’ve Got a Secret that originally aired on February 9, 1956:

The guest, Samuel J. Seymour, was the last surviving eyewitness to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. He was ninety-five years old when he appeared on TV, and he died a bit less than two months after the telecast.

I’ve always found this clip to be fascinating, and not just because of its intrinsic value as a kind of electronic relic. It also interests me because I was born three nights before it originally aired, which means that my parents, who were fans of I’ve Got a Secret, might possibly have watched it in the hospital. Of course I couldn’t have “known” Samuel Seymour, not even in theory, but it’s still true that our lives overlapped in time, just as it’s true that my own high-school piano teacher happened to be in the audience when Sergei Rachmaninoff gave his very last piano recital in Knoxville in 1943. For that matter, I once knew a man who saw Nijinsky dance and heard George Gershwin play the premiere of his Second Rhapsody in Boston in 1932.

We are so very, very close to what we think of as the distant past, and much of that distance has been all but erased by the invention of sound recording, film, and TV. Take a look at this video:

It’s a silent film of Camille Saint-Saëns conducting, shot around 1915. The soundtrack is an unrelated 1904 recording of Saint-Saëns playing the opening solo of his Second Piano Concerto, which was composed in 1868, followed by an improvised cadenza to another piece of his called Africa. At the end of the latter performance, you can briefly hear him speaking.

For the record, Saint-Saëns was born in 1835, the year in which Lucia di Lammermoor was composed and premiered, and died in 1921, the year in which Franklin Roosevelt contracted polio. He was present at the first concert performance of The Rite of Spring in Paris in 1914. He walked out midway through the piece, declaring that the composer was “mad.” The American Civil War was a mere blip on his screen, assuming that it made any impression on him at all.

What does it all mean? I’m damned if I know. I merely offer it for you to ponder, glossed by a quote that I’m sure you’ve encountered, surrounded by a context with which you may not be as familiar. George Santayana said it in The Life of Reason:

Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement: and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. This is the condition of children and barbarians, in whom instinct has learned nothing from experience.

Food for thought on a Monday morning.

* * *

Incidentally, Saint-Saëns may not have given any thought to the assassination of Lincoln, but another assassination played an interesting part in his later life. In 1908 he wrote the score for a silent film called The Assassination of the Duke of Guise:

It was, so far as is now known, the first film of any kind to feature a musical score by a composer of any significance.

In today’s Wall Street Journal I rejoice in Bedlam Theatre Company’s new off-off-Broadway productions of The Seagull and Sense and Sensibility. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Great theater isn’t about fancy sets or famous actors (though it doesn’t necessarily exclude either). It’s about imagination and intimacy. Given enough of both, a band of gifted unknowns can make theatrical magic in an empty room. That’s what Bedlam Theatre Company is doing with its no-budget off-off-Broadway productions of “The Seagull” and “Sense and Sensibility,” which are playing in repertory in a black-box performance space in downtown Manhattan that looks like the inside of a grungy warehouse. If you saw Bedlam’s versions of “Hamlet” and George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan,” performed under like circumstances in 2012 and 2013, you already know that no theater troupe in America is doing more creative classical revivals. These two shows, staged by Eric Tucker, Bedlam’s artistic director, are—if possible—even better.

Great theater isn’t about fancy sets or famous actors (though it doesn’t necessarily exclude either). It’s about imagination and intimacy. Given enough of both, a band of gifted unknowns can make theatrical magic in an empty room. That’s what Bedlam Theatre Company is doing with its no-budget off-off-Broadway productions of “The Seagull” and “Sense and Sensibility,” which are playing in repertory in a black-box performance space in downtown Manhattan that looks like the inside of a grungy warehouse. If you saw Bedlam’s versions of “Hamlet” and George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan,” performed under like circumstances in 2012 and 2013, you already know that no theater troupe in America is doing more creative classical revivals. These two shows, staged by Eric Tucker, Bedlam’s artistic director, are—if possible—even better.

Mr. Tucker is fielding an ensemble of 10 actors this time around instead of the four-person casts that covered all of the roles in “Hamlet” and “Saint Joan,” but his unpretentiously radical directorial style is otherwise unchanged. Instead of passively letting the action unfold before your eyes, you have to meet Bedlam halfway in your mind, for no attempt is made at conventional theatrical illusion: Men play women, women play men, people play animals. The décor amounts to a half-dozen cheap-looking chairs and tables, the costumes and lighting are dirt-plain and most of the audience is seated within arm’s length of the playing area. Yet the paradoxical result is a realism so persuasive that rather than viewing a pair of over-familiar “classics” for the umpteenth time, you feel as though you’re witnessing something that really happened, perhaps earlier today.

This is especially true of Mr. Tucker’s modern-dress version of Anya Reiss’ 2012 English-language adaptation of “The Seagull,” in which the language of Anton Chekhov’s play is colloquialized (“So what’s this writer guy like?”) and the action transposed from Russia in 1895 to America in 2014. By now such updatings are old hat, but this one works because the transposition is never stressed, much less made the whole point of the show. We are simply allowed to take it for granted that we’re seeing a play set in the present, so much so that Laura Baranik, who plays Nina, the ardent young girl who longs to go on the stage, speaks in the unmistakable tones of a millennial adolescent.

As always with Bedlam, the close physical proximity of players and audience is used to breath-catching effect…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, virtually all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Love Letters (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 1, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, reviewed here)

• On the Town (musical, G, contains double entendres that will not be intelligible to children, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• This Is Our Youth (drama, PG-13, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Indian Ink (drama, PG-13, closes Nov. 30, reviewed here)

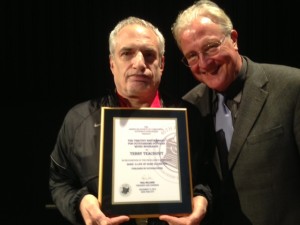

In case you missed the announcement in October, Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington, my most recent book, has won the Timothy White Award for Outstanding Musical Biography, one of the ASCAP Foundation’s annual Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Awards for “outstanding print, broadcast and new media coverage of music.”

In case you missed the announcement in October, Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington, my most recent book, has won the Timothy White Award for Outstanding Musical Biography, one of the ASCAP Foundation’s annual Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Awards for “outstanding print, broadcast and new media coverage of music.”

Alas, I wasn’t able to come to last night’s award ceremony in New York, so I asked my friend Paul Moravec, a member of ASCAP and my longtime operatic collaborator, to read the following statement on my behalf:

I thank ASCAP for this great honor, and I’m especially touched that it should be named after Deems Taylor and Virgil Thomson, two critics who were also composers of note and who, though they wrote mainly about classical music, were interested in and responsive to music of all kinds, including jazz. That has been my own path as well. I started out as a professional musician before becoming a full-time critic, and I both played and wrote about music of all kinds, jazz very much included. Today I not only write about theater but also write for the stage, including a play and the libretti for three operas.

If my work has any larger meaning, it is as a living symbol of the fact that at bottom, all art is one. In seeking to create and foster beauty, the artist speaks to all humans in all conditions, and endeavors to bring them closer together. That is what Duke Ellington, the subject of my book, did his whole life long: he sought to bring human beings together through the universal language of music, which knows no borders or boundaries. In honoring me, you honor him.

By the way, that really is Donald Fagen (who, I gather, both read and liked Duke) standing next to Paul, holding my award. He won one, too, for Eminent Hipsters.

An ArtsJournal Blog