“The dullard’s envy of brilliant men is always assuaged by the suspicion that they will come to a bad end.”

“The dullard’s envy of brilliant men is always assuaged by the suspicion that they will come to a bad end.”

Max Beerbohm, Zuleika Dobson

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Last week I wrote five Wall Street Journal, columns, a Commentary essay, and a fable, taught two classes, drove six hundred miles, saw a Broadway show, and went to a funeral. It was too much for me, and I now feel as though somebody worked me over with a rubber hose. On Wednesday I’ll be flying to St. Louis and driving from the airport to Smalltown, U.S.A., there to spend Thanksgiving with my brother and sister-in-law and a happy horde of hungry relatives. I return to New York on Saturday.

Last week I wrote five Wall Street Journal, columns, a Commentary essay, and a fable, taught two classes, drove six hundred miles, saw a Broadway show, and went to a funeral. It was too much for me, and I now feel as though somebody worked me over with a rubber hose. On Wednesday I’ll be flying to St. Louis and driving from the airport to Smalltown, U.S.A., there to spend Thanksgiving with my brother and sister-in-law and a happy horde of hungry relatives. I return to New York on Saturday.

For all these reasons, it seems to me as though I’ve had enough, at least for now. No blogging this week—just the usual regular postings, which will appear on schedule as always.

See you Monday.

In an extremely rare TV appearance on 200 Years of Woodwinds, a 1960 public-TV series that featured the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet, Samuel Barber talks with the members of the quintet, after which they perform his Summer Music. The players are Robert Cole on flute, John deLancie on oboe, Anthony Gigliotti on clarinet, Mason Jones on horn, and Sol Schoenbach on bassoon:

In an extremely rare TV appearance on 200 Years of Woodwinds, a 1960 public-TV series that featured the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet, Samuel Barber talks with the members of the quintet, after which they perform his Summer Music. The players are Robert Cole on flute, John deLancie on oboe, Anthony Gigliotti on clarinet, Mason Jones on horn, and Sol Schoenbach on bassoon:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the new Broadway revival of A Delicate Balance. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Everybody knows Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Not so “A Delicate Balance,” which came along four years later, in 1966, and failed to make the same culture-shifting stir. Though it won the Pulitzer Prize that “Virginia Woolf” absurdly failed to nail, the first production ran for only 132 performances, and the 1996 Broadway revival, despite glowing reviews, didn’t do much better. While “A Delicate Balance” is now seen regionally with some regularity, I doubt it would have returned to Broadway for a third try were it not for Glenn Close, who was last seen there 20 years ago and whose inclusion in the cast is making it—at last—a very hot ticket indeed.

Aside from Ms. Close’s presence, what has changed about “A Delicate Balance” in the intervening half-century is that its author has metamorphosed from American theater’s angry young man into its grumpy elder statesman. In between he was seen as a back number, a writer of eccentric, sometimes impenetrable plays who after “Virginia Woolf” couldn’t get a good review to save his life. At length the critical tide turned, but Mr. Albee is still what he always was, a wildly uneven author whose worst plays are so bad that it hardly seems possible that they were written by the same man who gave us the best ones. Where does “A Delicate Balance” fall on that spectrum? At its best, it’s thought-provoking and sometimes challenging, but it takes a long time to get moving, and I wonder whether modern-day audiences will be willing to wait for it.

Aside from Ms. Close’s presence, what has changed about “A Delicate Balance” in the intervening half-century is that its author has metamorphosed from American theater’s angry young man into its grumpy elder statesman. In between he was seen as a back number, a writer of eccentric, sometimes impenetrable plays who after “Virginia Woolf” couldn’t get a good review to save his life. At length the critical tide turned, but Mr. Albee is still what he always was, a wildly uneven author whose worst plays are so bad that it hardly seems possible that they were written by the same man who gave us the best ones. Where does “A Delicate Balance” fall on that spectrum? At its best, it’s thought-provoking and sometimes challenging, but it takes a long time to get moving, and I wonder whether modern-day audiences will be willing to wait for it.

The place is “a large and well-appointed suburban house.” The time is “now.” The occupants are Agnes and Tobias (Glenn Close and John Lithgow), a hard-drinking couple of the “upper-upper middle-middle” class (Mr. Albee’s phrase) who are leading the usual lives of quiet desperation, and Claire (Lindsay Duncan), Agnes’ hatchet-tongued alcoholic sister, who seems to have no occupation beyond drinking, playing the accordion and saying horrible things to everyone she meets. Enter Harry and Edna (Bob Balaban and Clare Higgins), Agnes and Tobias’ best friends, who drop in for (of course) a drink, confess to having become “frightened” for no specified reason, ask to spend the night and return a little later with all of their belongings. Agnes puts them up in the bedroom of Julia (Martha Plimpton), her grown daughter, who has been married four times and comes home in between husbands. Julia arrives and finds that her room is occupied, upon which all hell promptly breaks loose.

While the notion that well-do-do WASPs are dead inside is perhaps the least little bit overfamiliar, this is still a fairly promising setup for a theater-of-the-absurd comedy. But “A Delicate Balance” runs for two hours and forty-five minutes, and nothing much happens until midway through the evening. Instead we get a truckload of genteel drawing-room badinage, none of which glitters nearly so much as Mr. Albee supposes…

Ms. Close’s performance is quiet, tasteful and underprojected, not surprising for an actor who has been absent from the stage for so long. Mr. Lithgow, by contrast, is in extraordinary form, by turns tightly inhibited and almost shockingly anguished….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A scene from the 1973 film version of A Delicate Balance, directed by Tony Richardson and starring Katharine Hepburn, Paul Scofield, Joseph Cotten, and Betsy Blair:

Just as I was sitting down yesterday morning to write my review of A Delicate Balance, I got a call from The Wall Street Journal telling me that Mike Nichols had died and asking if I could also write his obituary—right now. I took a very deep breath, quickly looked up a couple of favorite anecdotes, and went to work. The results were posted last night on the Journal‘s website:

Just as I was sitting down yesterday morning to write my review of A Delicate Balance, I got a call from The Wall Street Journal telling me that Mike Nichols had died and asking if I could also write his obituary—right now. I took a very deep breath, quickly looked up a couple of favorite anecdotes, and went to work. The results were posted last night on the Journal‘s website:

It hardly seems that Mike Nichols is dead—not just because he lived so long and productive a life, but because the work continued to pour out of him all the way to the finish line. Just last year he directed a Broadway revival of Harold Pinter’s “Betrayal.” There seemed no end to his burgeoning vitality. The shape of his career tells you everything about the unstoppable inner force that pushed him forward: He started out as a standup comedian and ended up one of a handful of directors to have won equal fame on Broadway and in Hollywood. “If you’re in any contest at all where you can win or lose, try to win,” Nichols told André Previn. He usually won. He bagged a best-director Oscar, two best-director Emmys, seven best-director Tonys—and in 1961, a Grammy for best comedy album of the year.

It isn’t hard to figure out what made Nichols so competitive. Born in Berlin in 1931, he got out of Germany at the age of seven, mere steps ahead of the Holocaust. After that, nobody had to tell him that Jews got no favors. Characteristically, he claimed that it was an advantage. “The thing about being an outsider,” he said in 2012, “is that it teaches you to hear what people are thinking because you’re constantly looking for the people who just don’t give a damn.”

Nichols made his name in the Fifties by improvising supremely sharp-witted comedy routines with Elaine May. The lightning-quick timing that he cultivated on nightclub stages served him well when he took up directing in 1963. During a rehearsal for the Broadway premiere of Neil Simon’s “The Odd Couple,” he got into a shouting match with Walter Matthau. “You’re emasculating me!” the actor shouted. “Give me back my balls!” “Certainly,” Nichols replied, then snapped his fingers to summon the stage manager. “Props!”

Nichols’ work was unshowy, even self-effacing. “It’s not a filmmaker’s job to explain his technique, but to tell his story the best way he can,” he said. Hence no one will ever think of him as a groundbreaker, a radically original creative artist. He was, rather, an interpreter, and in the studio he almost always did his best work with familiar material like Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (his first film) and Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America,” both of which clearly convey the visceral impact of the plays on which they were based. I suspect that few of his other films will be as well remembered. Even “The Graduate,” which vaulted him into the pantheon of Hollywood superstars in 1968, now looks like a period piece, a carefully posed snapshot of a key moment in postwar American culture.

But the fact that Nichols did make films means that he himself will likely be remembered longer than any other American stage director of his generation. No art is more evanescent than that of the theatrical director, which evaporates when the show closes. Yet Nichols’ track record on Broadway was astonishing….

Read the whole thing here.

* * *

Mike Nichols and Elaine May perform “The $65 Funeral” on The Jack Paar Program:

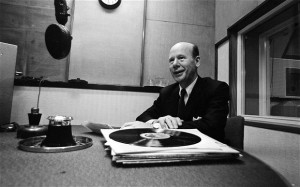

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I talk about Desert Island Discs, the BBC’s longest-running radio program. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The BBC aired the three thousandth episode of “Desert Island Discs,” its longest-running radio series, last week. The anniversary attracted no attention on this side of the Atlantic, however, because the perennially popular “Desert Island Discs,” whose guests are invited to select and discuss the eight records they’d take with them were they to be shipwrecked on a distant isle, has never been heard in the U.S. save by fanatical Anglophiles with shortwave radios….

Fortunately, the “Desert Island Discs” page on the BBC’s website contains a fully searchable database that allows users to listen to any of the 1,500-odd surviving episodes. In addition, you can use the database to find out which records were picked by everyone who has appeared on “Desert Island Discs” since it first went on the air in 1942.

Fortunately, the “Desert Island Discs” page on the BBC’s website contains a fully searchable database that allows users to listen to any of the 1,500-odd surviving episodes. In addition, you can use the database to find out which records were picked by everyone who has appeared on “Desert Island Discs” since it first went on the air in 1942.

Not only is the “Desert Island Discs” database a largely unquarried diamond mine for scholars, but it’s dangerously easy to blow an evening looking up guest after guest on your laptop. The genius of the show, which was created by Roy Plomley, is that it invites not just musicians but celebrities of all sorts to talk about the records they love. Among the people who have appeared on “Desert Island Discs” are, just for starters, Louis Armstrong, Lauren Bacall, Isaiah Berlin, Eric Clapton, Cyril Connolly, Aaron Copland, Elvis Costello, Noël Coward, Margot Fonteyn, John Gielgud, Stephen Hawking, Alfred Hitchcock, David Hockney, Philip Larkin, Liberace, J.K. Rowling, Jimmy Stewart and Desmond Tutu….

The first thing you notice are the surprises. Who on earth would have expected for Margaret Thatcher to choose Bob Newhart’s “Introducing Tobacco to Civilization” to cart off to her desert island along with Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto?…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

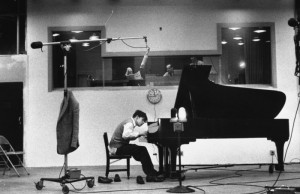

Anybody who writes about Desert Island Discs can scarcely avoid wanting to play along, so here goes. The program invites you to choose eight records. These are mine:

• Bach’s Goldberg Variations, recorded in 1955 by Glenn Gould

• Bach’s Goldberg Variations, recorded in 1955 by Glenn Gould

• Mozart’s G Minor Symphony, performed by Benjamin Britten and the English Chamber Orchestra

• Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, performed by Copland and the Columbia Chamber Ensemble

• Louis Armstrong’s 1928 recording of “West End Blues”

• Nancy LaMott’s recording of “Skylark,” written by Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer

• The complete performance of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot recorded in 1956 by Bert Lahr, E.G. Marshall, Kurt Kasznar, and Alvin Epstein, the cast of the first Broadway premiere

If my “record player” will also play videos, I’d like to bring along

• New York City Ballet’s 1977 PBS performance of George Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments, whose score is by Paul Hindemith

• Jean Renoir’s La règle du jeu, the greatest movie ever made

If not, I’d opt for

• Beethoven’s G Major Piano Concerto, recorded in 1942 by Artur Schnabel, Frederick Stock, and the Chicago Symphony

• Steely Dan’s Aja

You are always asked to pick one favorite record on Desert Island Discs, and mine is the Goldberg Variations.

You are always asked to pick one favorite record on Desert Island Discs, and mine is the Goldberg Variations.

In addition, you’re also asked to pack a book and a “luxury item.” It’s stipulated that the island already contains copies of the complete works of Shakespeare and the Bible (though that may change). In that case, my book would be Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time and my luxury item would be my favorite painting, Paul Cézanne’s “The Garden at Les Lauves.” To be sure, the latter item is one of the Phillips Collection’s most celebrated and treasured possessions…but I want it anyway. (I promise to give it back to the Phillips if rescued!)

An ArtsJournal Blog