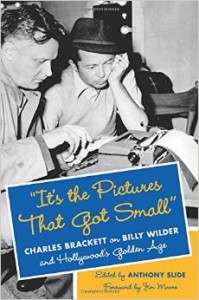

My monthly essay in the latest issue of Commentary takes as its point of departure the publication of ”It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, which will be published at the end of November by Columbia University Press:

My monthly essay in the latest issue of Commentary takes as its point of departure the publication of ”It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, which will be published at the end of November by Columbia University Press:

Of the studio-era Hollywood directors whose best films have proved to be of lasting value, Billy Wilder was the one who brought off the least likely feat: He won mass popularity by making movies that embody a dark and bitter vision of the world. Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950), the most impressive films Wilder made in the first part of his career, were not only financially successful but critically acclaimed as well. He was a writer, moreover, who started directing his own scripts in 1942 primarily to protect the words—a fact that set him apart from nearly all his contemporaries and helped to establish him as a key figure of Hollywood’s golden age.

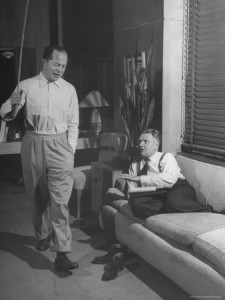

The modern-day tendency to see the director of a film as its prime creative mover, however, has obscured the fact that Wilder’s scripts were invariably written with collaborators. He collaborated with the same man, Charles Brackett, on all but one of the features he co-wrote in Hollywood prior to 1951. In 1948, he went so far as to describe himself and Brackett, who produced the films that they wrote together, as “the happiest couple in Hollywood.” And yet, in that same year, Wilder unilaterally decided to dissolve their partnership and collaborate with others. He never worked with Brackett again.

Neither man publicly discussed their break save in general terms, nor did they talk with any specificity about how they wrote screenplays together. Because of this mutual reticence, and because Brackett wrote no screenplays of any consequence without Wilder, his name is now familiar only to film critics and historians.

Hence the importance of “It’s the Pictures That Got Small”: Charles Brackett on Billy Wilder and Hollywood’s Golden Age, a new volume of entries from his hitherto unpublished diary. In addition to relating his side of the break with Wilder and providing an exact description of the nature of their collaborative process, the book reveals that Brackett was a talented writer in his own right and a shrewd chronicler of the film industry in the 1930s and ’40s.Above all, “It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is an indispensable guide to the complex, increasingly awkward relationship between two men who had next to nothing in common and yet contrived to make a fair number of the studio system’s finest films….

Read the whole thing here.