I’m teaching a graduate seminar this semester at New York’s Mannes College of Music. It’s called “How to Write and Speak About Music,” and my seven students (whom I refer to, though not in their presence, as “my kids”) are all hard-working, immensely likable, and half my age, meaning that I’m learning at least as much from them as they are from me.

The other day I mentioned that Haydn was one of my favorite composers. One of my students told me after class that his music had never spoken to her. I said that I warmed to his humor and (in Alec Guinness’ apt phrase) “clear common sense,” an opinion that I expressed at greater length nine years ago in an essay for Commentary.

The other day I mentioned that Haydn was one of my favorite composers. One of my students told me after class that his music had never spoken to her. I said that I warmed to his humor and (in Alec Guinness’ apt phrase) “clear common sense,” an opinion that I expressed at greater length nine years ago in an essay for Commentary.

“Maybe I’m still too young to appreciate those things,” my student replied, without any perceptible glimmer of irony.

I wonder whether my face betrayed the astonishment that I felt upon hearing her perfectly serious words. When I was in my twenties, it would never have occurred to me to say anything like that about any known subject, least of all to a much older person. From early adolescence onward, I took it for granted that (A) I knew everything about everything and (B) my point of view was ex hypothesi more valid than that of my seniors. It wasn’t until I moved to New York at the age of twenty-nine that I came to the belated conclusion that I was, in fact, all wet.

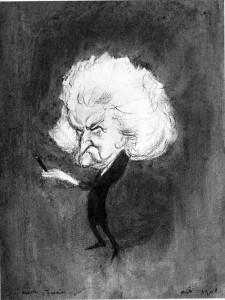

Mark Twain is generally credited with the following quip:

When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it turns out upon further investigation that he may or may not have said it, and that if he did, he almost certainly said it very differently. Be that as it may, Twain (or whoever) was right and then some, a fact that has since been pounded into me over and over again from the hardest possible experience. My father, who wasn’t a reader and so was never given to talking in quotations, did like to trot out from time to time the following untraceable proverb: “Too soon we grow old, too late we grow smart.” He always said it with rue, an emotion that is also mostly alien to the young. Now I know better, about that and countless other things.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it turns out upon further investigation that he may or may not have said it, and that if he did, he almost certainly said it very differently. Be that as it may, Twain (or whoever) was right and then some, a fact that has since been pounded into me over and over again from the hardest possible experience. My father, who wasn’t a reader and so was never given to talking in quotations, did like to trot out from time to time the following untraceable proverb: “Too soon we grow old, too late we grow smart.” He always said it with rue, an emotion that is also mostly alien to the young. Now I know better, about that and countless other things.

Hence my extreme surprise upon hearing my student say what she said. I’m sure she meant it, too, since she strikes me as utterly guileless, albeit in the nicest possible way. And I find myself wondering: is her modesty in the face of experience a generational characteristic, or is it just her?

I don’t know, and I doubt I ever will. To be sure, most of my friends, as I’ve remarked more than once, are younger than I am, and I like it that way. I learn from them, and I also draw vitality from their youthful energy. At the same time, though, I’m well aware of the importance of keeping a respectful distance from them. Nothing is more inappropriate, or more potentially humiliating, than for a middle-aged man to engage in the practice of what Kingsley Amis testily described in Girl, 20, my second favorite of his novels, as “arse-creeping youth.”

Here’s something that I wrote in this space a decade ago, on the occasion of my forty-eighth birthday:

Must there come a moment when it’s wiser to stick to the cards in your hand, to deepen your understanding of what you already know? My hair stood up when I stumbled on the following sentence in Jack Richardson’s Memoir of a Gambler: “As we moved along in the police wagon, I had the slightly unclean feeling of the man who keeps company with those much younger than himself.” Might I have reached that terrible time without knowing it—the time when middle-aged people embarrass themselves by pretending to be that which they are not, forgetting that they shall never be again as they were? That’s a scary thought.

So I have no plans to probe my student as to her overall attitude toward the Wisdom of Her Elders, such as it may or may not be. Nevertheless, I’m impressed by her own wisdom, at least as it applies to the music of Franz Joseph Haydn. I mentioned Alec Guinness a moment ago, so allow me to circle back and quote here the complete passage from his diaries to which I referred: “For me there are two salves to apply when I feel spiritually bruised—listening to a Haydn symphony or sonata (his clear common sense always penetrates) and seeking out something in Montaigne’s essays.”

Guinness was a very old man when he said that. I hope my student will be lucky enough to feel the same way when she grows a bit older—but I wouldn’t dream of telling her so. I know better than to push my luck.

* * *

Alfred Brendel plays Haydn’s Sonata in E Flat, Hob. XVI:49, at Aldeburgh’s Snape Maltings Concert Hall in 2000. He was sixty-nine years old when he taped this performance for the BBC: