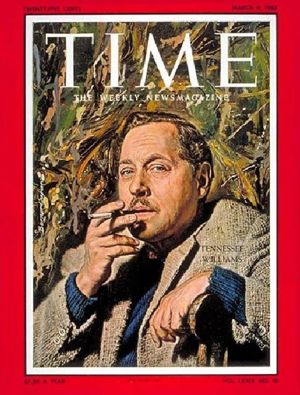

I’ve always had sharply mixed feelings about Tennessee Williams, and I explore them at length in the new issue of Commentary. The occasion is an essay about John Lahr’s important new biography of Williams:

I’ve always had sharply mixed feelings about Tennessee Williams, and I explore them at length in the new issue of Commentary. The occasion is an essay about John Lahr’s important new biography of Williams:

When asked to name France’s greatest poet, André Gide quipped, “Victor Hugo, hélas!” Though John Lahr unequivocally describes Tennessee Williams as “America’s greatest playwright,” one comes away from his book wondering whether he, too, might have similar reservations about his subject’s ultimate stature, given the paucity of his accomplishments. Indeed, when Lahr remarks on the next-to-last page of Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh that Williams created “characters so large that they became part of American folklore,” the six whom he cites are all from The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

One need not create a large body of major work in order to crack the history books. But a prolific artist whose output is for the most part gravely flawed is by definition problematic, and few artists of stature have been more problematic than Williams….

Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh ends with a chronology of Williams’s life whose final item, from 2011, is significant in this connection: “The Comédie-Française in Paris produces Un tramway nommé Désir, staged by American director Lee Breuer, the first play by a non-European playwright in the company’s 331-year history.” Of such tributes is immortality made. But the fact that Streetcar, Cat, and The Glass Menagerie are the only plays by Williams that have ever been successfully revived on Broadway says much about the likely survival of most of the rest of his output. For like most autobiographical artists, he had only one story to tell, and after he transformed its characters into archetypes and told it twice—literally in The Glass Menagerie, symbolically in Streetcar—he had little choice but to tell it again with increasingly predictable variations….

Read the whole thing here.