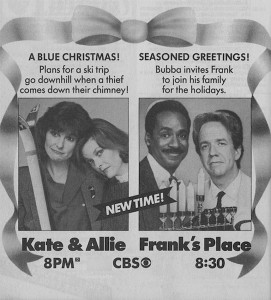

Twenty-seven years ago next month, a black-themed half-hour comedy series called Frank’s Place made its debut on CBS. I tuned in the first episode solely because I’d been a fan of WKRP in Cincinnati, one of whose cast members, Tim Reid, was the star of the new show, which was set in modern-day New Orleans. But I liked what I saw very much, and continued to watch Frank’s Place throughout its run.

Twenty-seven years ago next month, a black-themed half-hour comedy series called Frank’s Place made its debut on CBS. I tuned in the first episode solely because I’d been a fan of WKRP in Cincinnati, one of whose cast members, Tim Reid, was the star of the new show, which was set in modern-day New Orleans. But I liked what I saw very much, and continued to watch Frank’s Place throughout its run.

Except for the racial angle, the premise of Frank’s Place was simple to the point of obviousness: Reid played a middle-class black academic from Boston who inherited a Creole-style restaurant from his father and decided to move to New Orleans to run it. The show itself, however, was radically different in style and tone from most of the other popular sitcoms of the day, WKRP included, for it was an unusually well-written single-camera “dramedy” without a laugh track. Such series are common enough now, but they were rare in 1987, and the fact that Frank’s Place had a mostly black cast made it rarer still.

Not surprisingly, Reid understood full well what he’d gotten himself into. “Hugh, I think this is brilliant, but it scares hell out of me,” he said to Hugh Wilson, the show’s creator. “I’ve never seen this on television. I’m not sure television is ready for this.” Nor was it: Frank’s Place was cancelled after a single twenty-two-episode season, and today it is known only to TV historians and aging fans.

Not surprisingly, Reid understood full well what he’d gotten himself into. “Hugh, I think this is brilliant, but it scares hell out of me,” he said to Hugh Wilson, the show’s creator. “I’ve never seen this on television. I’m not sure television is ready for this.” Nor was it: Frank’s Place was cancelled after a single twenty-two-episode season, and today it is known only to TV historians and aging fans.

Frank’s Place has never been released on DVD, but a handful of episodes can be viewed on YouTube. One of them, “Frank Joins the Club,” in which Reid is invited to join an upper-middle-class social club for light-skinned black men, has remained clear in my memory ever since it originally aired:

So far as I know, this episode of Frank’s Place was the first time that the near-unmentionable topic of intraracial prejudice was discussed with any kind of candor on network TV. While I’d read about it in books like The Autobiography of Malcolm X, it wasn’t until I saw “Frank Joins the Club,” which was written by the playwright Samm-Art Williams, that I became aware that it still existed in the black community, and began to grasp how it affected the everyday lives of black Americans.

Needless to say, I had no earthly idea back in 1987 that I would someday write full-length biographies of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington that dealt with intraracial prejudice, much less a one-man play about Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his Jewish manager. Still, I rather doubt that I would have written the following speech from Satchmo at the Waldorf in quite the same way had I not seen “Frank Joins the Club”:

Needless to say, I had no earthly idea back in 1987 that I would someday write full-length biographies of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington that dealt with intraracial prejudice, much less a one-man play about Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his Jewish manager. Still, I rather doubt that I would have written the following speech from Satchmo at the Waldorf in quite the same way had I not seen “Frank Joins the Club”:

Down in New Orleans, them light-skin colored, them Creoles, they think they hot shit, look down on the rest of us like we was dirt. Jelly Roll Morton, he like that. Had that diamond in his front tooth. Used to swan around saying, “Don’t call me colored—I’m one hundred percent French.” But you know what? He still had to eat out back in the kitchen, just like me.

That why I call myself “Louis,” not “Louie.” Mr. Glaser, he call me “Louie.” White folks all call me “Louie.” The announcer here, he call me “Louie” every night before the show. That’s O.K., call me what you want, but I ain’t no goddamn Frenchman, ain’t no Creole, ain’t no “Lou-ie.” I’m black. Black as a spade flush. Woke up black this morning, black when I go to bed, still gonna be black when I get up tomorrow. Don’t like it, you can kiss my black ass.

I’ve never before had occasion to write about Frank’s Place, mainly because it wasn’t until the show turned up on YouTube that I was able to confirm the accuracy of my faded memories of its quality. Truth to tell, I was a bit afraid to watch “Frank Joins the Club” for fear of being disillusioned. But it turns out to be as good as I remembered, and having finally seen it for a second time long after the fact, I want to pay a debt. Thank you, Tim Reid, Hugh Wilson, and Samm-Art Williams, for teaching me a lesson about the complexity of race relations in America that I took to heart and never forgot. I hope you get to see Satchmo at the Waldorf someday and find out what you wrought.

* * *

To read Dave Walker’s 2002 New Orleans Times-Picayune feature story about Frank’s Place, go here.