• I’ve been rereading Jeanine Basinger’s The Star Machine, one of the smartest and most illuminating books ever written about studio-era Hollywood. It contains an especially good chapter about Mickey Rooney in which Basinger tells the fascinating story of how A Family Affair, the first Andy Hardy movie, made him a child star in 1937. It wasn’t intended to do any such thing: MGM was grooming another actor in the film, Eric Linden, for stardom. But the public, as is so often the case, drew its own conclusions, which Basinger sums up in two pointed sentences: “Today, no one has heard of Eric Linden. Everybody knows Mickey Rooney.”

Well…yes and no. Rooney was a big, big star until he joined the Army in 1944, but when he returned to Hollywood two years later, it was all over. While he continued to work to the very end of his long life—his last film, Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, will be released in December, seven months after he died at the age of ninety-three—he never again played a leading role in a movie of any great distinction. Nor were very many of his supporting parts noteworthy, though Rooney did manage to transform himself into a character actor of no small accomplishment, as can be seen in the 1962 film version of Rod Serling’s Requiem for a Heavyweight. And while his obituaries were both lengthy and respectful, I suspect that their length was more a matter of his longevity (he was one of the last survivors of the studio system) than anything else. Wonderful though he was in them, scarcely anybody now watches the movies that Rooney made in the Thirties and early Forties, not even the fluffy let’s-put-on-a-show musicals in which he co-starred with Judy Garland, and I can’t imagine that very many people under the age of sixty have more than a vague idea of who he was, much less why it mattered.

Even more interesting to me, however, was something that I learned from the Rooney chapter in The Star Machine, which is that one of his co-stars in A Family Affair was Julie Haydon, who played his sister. Unless you know a lot about the history of Broadway, you won’t recognize Haydon’s name, for she appeared in only a handful of films, none of them particularly noteworthy. It was as a stage actress that she made her name, such as it was, and she is now best known to history for having been the longtime girlfriend and eventual wife of George Jean Nathan, the stiletto-tongued drama critic who co-founded the American Mercury with H.L. Mencken and was the real-life model for Addison DeWitt, the venomous critic played by George Sanders in All About Eve. (For the record, Lillian Gish preceded her in Nathan’s bed.)

It was widely taken for granted on Broadway that Haydon got cast in plays because of her relationship with Nathan, which was an open secret, so much so that Damon Runyon is said to have had them in mind when he created the characters of Miss Adelaide and Nathan Detroit in the short story that Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser later turned into into Guys and Dolls.

It was widely taken for granted on Broadway that Haydon got cast in plays because of her relationship with Nathan, which was an open secret, so much so that Damon Runyon is said to have had them in mind when he created the characters of Miss Adelaide and Nathan Detroit in the short story that Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser later turned into into Guys and Dolls.

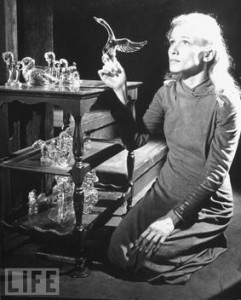

On the other hand, she received reviews that were much more than merely respectful throughout her comparatively brief stage career, and she also created the role of Laura Wingfield in the original production of The Glass Menagerie. No matter whom she knew, it’s hard to imagine that she would have landed that demanding part had she not been competent enough to play opposite Laurette Taylor, the first Amanda, who gave what is universally regarded as one of the greatest performances in the history of the American stage. As for Haydon, no less qualified an observer than Stark Young, that toughest and most knowing of critical customers, wrote in The New Republic that she gave “one of her translucent performances of a dreaming, wounded, half-out-of-this-world young girl.”

Haydon got a much shorter New York Times obituary of her own when she died in 1994. It decorously overlooked the precise nature of her relationship with Nathan, and devoted one sentence to her film career. And that was that: now she belongs to the ages, and the ages don’t seem to care much for her. Or for Mickey Rooney, sad to say. Nostalgia only lasts as long as the people who feel it are still alive, and its value depreciates with fearful velocity. Few things are more ephemeral than the fame of a movie star who didn’t make any great movies—unless it’s the reputation of a stage actor who didn’t play any great film roles. Try though she might, not even a historian as fine as Jeanine Basinger can do much of anything about that.

Haydon got a much shorter New York Times obituary of her own when she died in 1994. It decorously overlooked the precise nature of her relationship with Nathan, and devoted one sentence to her film career. And that was that: now she belongs to the ages, and the ages don’t seem to care much for her. Or for Mickey Rooney, sad to say. Nostalgia only lasts as long as the people who feel it are still alive, and its value depreciates with fearful velocity. Few things are more ephemeral than the fame of a movie star who didn’t make any great movies—unless it’s the reputation of a stage actor who didn’t play any great film roles. Try though she might, not even a historian as fine as Jeanine Basinger can do much of anything about that.

* * *

Mickey Rooney and Margaret Marquis in a scene from A Family Affair:

Mickey Rooney and Jackie Gleason in a scene from the film version of Requiem for a Heavyweight: