• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer:

• A cyberfriend writes to remind me that when Charles Dickens visited America for the first time in 1842, he was mobbed wherever he went, an experience that he described in a letter to John Forster, his friend and biographer:

I can do nothing that I want to do, go nowhere where I want to go, and see nothing that I want to see. If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude. If I stay at home, the house becomes, with callers, like a fair. If I visit a public institution, with only one friend, the directors come down incontinently, waylay me in the yard, and address me in a long speech. I go to a party in the evening, and am so inclosed and hemmed about by people, stand where I will, that I am exhausted for want of air. I dine out, and have to talk about everything to everybody. I go to church for quiet, and there is a violent rush to the neighbourhood of the pew I sit in, and the clergyman preaches at me. I take my seat in a railroad car, and the very conductor won’t leave me alone. I get out at a station, and can’t drink a glass of water, without having a hundred people looking down my throat when I open my mouth to swallow. Conceive what all this is! Then by every post, letters on letters arrive, all about nothing, and all demanding an immediate answer. This man is offended because I won’t live in his house; and that man is thoroughly disgusted because I won’t go out more than four times in one evening. I have no rest, or peace, and am in a perpetual worry.

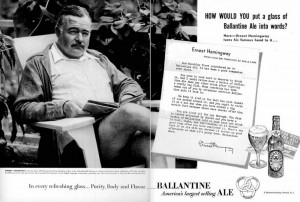

I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.

I suppose a modern-day reader might regard this as a nice problem to have, but what strikes me most forcibly about Dickens’ dilemma (if you want to call it that) is that it was a novelist who was having it. Today it’s unimaginable that any writer would be treated that way, whether in America or elsewhere. Our “rock stars” are…well, rock stars. Or, more likely, movie and TV stars. We simply don’t confer mass celebrity on writers nowadays. If I had to guess, I’d say that Ernest Hemingway was the last novelist of consequence whom a considerable number of Americans would have been at all likely to know by sight—he was, in fact, famous enough to be paid to endorse products—and he died more than a half-century ago.

Is this loss of status a bad thing? Very possibly not. The poet L.E. Sissman, about whom I wrote not long ago, believed that serious writers should keep to themselves:

In a word, the serious writer must take serious vows if he is to concentrate on his chief aim. A vow of silence, except through his work. A vow of consistency, sticking with writing to the exclusion of other fields. A vow of ego-chastity, abstaining from adulation. A vow of solitude, or at least long periods of privacy. A vow of self-regard, placing the self as writer before the self as personality.

He may have been right, too, though I’ve expressed reservations about it. Nevertheless, I know that I wouldn’t ever want to be enough of a celebrity to draw crowds in the street, though I readily confess to getting a kick out of being (very, very occasionally) recognized there. David Bowie said it: “I think fame itself is not a rewarding thing. The most you can say is that it gets you a seat in restaurants.” So does a reservation, and nobody bothers you while you eat.

* * *

Stephen King appears in an American Express commercial: