In 2001 I wrote a review of the film version of Daniel Clowe’s Ghost World that was published in Crisis. I recently had occasion to think about the film, and thought it might be interesting to post what I wrote about it thirteen crowded years ago.

In 2001 I wrote a review of the film version of Daniel Clowe’s Ghost World that was published in Crisis. I recently had occasion to think about the film, and thought it might be interesting to post what I wrote about it thirteen crowded years ago.

For the record, I wrote this review immediately after having seen Ghost World for the first time, and there are a few details that I probably would have changed after seeing it again. Nevertheless, I feel the same way today.

* * *

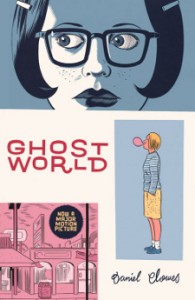

Good art, like grace, sometimes comes in peculiar-looking packages. Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World, a screen version of the underground comic book by Daniel Clowes, is a bleakly melancholic comedy about a pair of foul-mouthed teenage girls. You wouldn’t expect it to be much more than a symptom of the degraded state of postmodern American life—but you’d be wrong. Not since Kenneth Lonergan’s masterful You Can Count on Me last year have I seen a movie that cuts as close to the bone. It is by far the best American film of the year to date and among the finest of any kind to be released in the past decade.

Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson), Clowes’s anti-heroines, have spent the whole of their short lives trapped in a grubby pop-culture hell of strip malls, convenience stores, and round-the-clock Muzak. Their only defense against this smothering tackiness is to embrace it with a sneer, hanging out in faux-Fifties diners and mocking everything they see and everyone they meet. They are best friends—indeed, they have no other friends, except for Josh (Brad Renfro), a hapless boy whom they delight in tormenting—and it soon becomes apparent that much of their contempt is defensive, for nobody else seems to like them.

As Ghost World begins, Enid and Rebecca have just graduated from high school and are looking for an apartment to share, having decided to skip college and go to work. For all her seeming alienation, Rebecca turns out to be perfectly willing to swallow her disgust, get a nine-to-five job at a coffee bar, and become a reluctant member of the “ghost world” of adulthood. Enid, who is both brighter and more idealistic than Rebecca, is looking for something different, and she finds it in the unlikely person of Seymour (Steve Buscemi), a buck-toothed, middle-aged corporate wheelhorse who collects old blues 78s, loves W.C. Fields movies, and hasn’t been out on a date in four years.

Enid takes it upon herself to find him a girlfriend, explaining to the mystified Rebecca that even though he is a “clueless dork,” he is also “the exact opposite of all the things I hate.” In time, their mutual misanthropy draws them closer together, and Enid, whose own father (Bob Balaban) is pathetically prissy and ineffectual, comes to see the self-loathing Seymour as a kind of role model, a man of taste who has found a way to live in a tasteless world without compromising his bumbling integrity.

If that were as far as Ghost World went, it would be nothing more than a smart teen-angst flick with a keen satirical edge. But Zwigoff and Clowes take another, far riskier step: Enid seduces Seymour, an act of terrible irresponsibility to which she is driven less by lust than loneliness. Though she fantasizes about running away with him, their friendship is shattered by this brief sexual encounter, and the movie comes to a sad and ambiguous close as she boards a bus and departs on a solitary pilgrimage to parts unknown, leaving behind the wreckage of her lost youth.

Thora Birch, a raven-haired nineteen-year-old who plays Enid with a heartbreaking combination of cynicism and fragility, also appeared in American Beauty (1999). Ghost World may seem at first glance to echo that smug film’s unearned contempt for suburban life. But American Beauty offered easy answers to loaded questions (that’s why it won so many Oscars—Hollywood gives prizes only to movies that tell us what it wants to hear), whereas Ghost World is a movie without any answers at all. That is the source of its pathos. Like every teenager, Enid longs to be shown how to live, but the ghostly adults who drift in and out of her unhappy life offer her no counsel. Instead, she has been set adrift on the sea of relativity, looking for a safe harbor on an uncharted coast.

Thora Birch, a raven-haired nineteen-year-old who plays Enid with a heartbreaking combination of cynicism and fragility, also appeared in American Beauty (1999). Ghost World may seem at first glance to echo that smug film’s unearned contempt for suburban life. But American Beauty offered easy answers to loaded questions (that’s why it won so many Oscars—Hollywood gives prizes only to movies that tell us what it wants to hear), whereas Ghost World is a movie without any answers at all. That is the source of its pathos. Like every teenager, Enid longs to be shown how to live, but the ghostly adults who drift in and out of her unhappy life offer her no counsel. Instead, she has been set adrift on the sea of relativity, looking for a safe harbor on an uncharted coast.

Walker Percy once pointed out that a visit to the neighborhood theater is for many Americans “maybe the only point in the day, or even the week, when someone (a cowboy, a detective, a crook) is heard asking what life is all about, asking what is worth fighting for—or asking if anything is worth fighting for.” Out of that insight grew The Moviegoer, a novel about a man who goes to the movies in order to narcotize himself against the shallowness of American life, unaware that by doing so he has embarked on a search for meaning that will ultimately end in his embrace of Catholicism. As improbable as it may sound, Ghost World reminded me quite strongly of Percy’s great novel. To be sure, Enid lacks the spiritual consciousness that helped Percy’s protagonist, Binx Bolling, find his way out of the slough of despond, but she is just as surely going forth on a similar quest, and the fact that she is doing so without benefit of moral guidance makes her plight all the more moving.

I could go on and on about Ghost World, and I do want at least to mention Steve Buscemi’s uncanny performance as Seymour—it is so true to life that it will make you squirm in your seat—and David Kitay’s wistful score, which serves as a quiet reminder that Enid and Rebecca are far more vulnerable than they pretend.

By now, though, I suspect that more than a few people are reading this review with raised eyebrows, to which I can only reply that Ghost World is so good that it caught me off guard. It has been a frightful year for American movies, especially those aimed at adolescents, and the last thing I expected from Terry Zwigoff and Daniel Clowes was a film full of felt life and exactly rendered social observation (though one of the most striking aspects of Ghost World, as it happens, is the subtle way in which Zwigoff has imported the exaggeration and semiabstract simplicity of comic-book art into a cinematic context). You may find it uncomfortable, but you will also find it revelatory.

* * *

Skip James’ 1931 recording of “Devil Got My Woman,” as heard on the soundtrack of Ghost World: