Michael Steinman, one of my favorite bloggers, recently posted something poignant about the central importance of music in his life:

Michael Steinman, one of my favorite bloggers, recently posted something poignant about the central importance of music in his life:

Although I am by nature optimistic and hopeful, before 2004 I was seriously unhappy for long periods of time—situational rather than biochemical despair. The reasons for my sadness are not relevant here. When I was most hopeless, I thought seriously of ending my life. I checked out the Hemlock Society website (earnest but very complicated) and lay on my bed thinking of the items I would purchase from Home Depot that would do the job.

But one thought recurred in the darkness, “Is there any guarantee you will be able to hear music—Louis Armstrong first and everyone else you love—if you kill yourself?” It kept me from putting my plans into action….

I’ve never felt suicidal, but beyond that I think I know exactly what Michael means. While I can, if absolutely necessary, imagine living without music, it would be like living without salt, or love. Kingsley Amis put it nicely when he wrote that “only a world without love strikes me as instantly and decisively more terrible than one without music. Yes, friendship would beat music too, but not instantly.” Indeed, I sometimes doubt that I could truly love a person to whom music wasn’t important—and wonder whether that might possibly be a failing on my part.

All that said, I also know that music is not the first priority in my life. If I had to choose between reading and listening to music, I’d choose reading—with extreme reluctance, to be sure, but without a shadow of doubt.

In a sense, I made that choice, or something close to it, when I decided to become a professional writer instead of continuing to pursue my budding career as a performing musician, splitting the difference by writing about music. Nevertheless, it was a clear-cut choice, and I know why I made it. For one thing, I was better at writing than at playing. At least as important, though, was my belated recognition that for all my passionate love of music, it simply didn’t occupy enough of my mind to satisfy my curiosity about the world. I was interested in too many other things, and I knew that I could write about all of them. To make a living making music, by contrast, is—must be—an all-consuming enterprise, and I wasn’t prepared to be consumed by it.

In a sense, I made that choice, or something close to it, when I decided to become a professional writer instead of continuing to pursue my budding career as a performing musician, splitting the difference by writing about music. Nevertheless, it was a clear-cut choice, and I know why I made it. For one thing, I was better at writing than at playing. At least as important, though, was my belated recognition that for all my passionate love of music, it simply didn’t occupy enough of my mind to satisfy my curiosity about the world. I was interested in too many other things, and I knew that I could write about all of them. To make a living making music, by contrast, is—must be—an all-consuming enterprise, and I wasn’t prepared to be consumed by it.

So I walked away from the bandstand, and though I’ve spent many an hour thinking about the choice I made, I’ve never thought twice about the wisdom of having made it. As I wrote in this space eight years ago in an essay about the last time I played bass in public:

Somebody asked me once if I were a frustrated musician. “No,” I said, “I’m a fulfilled writer.” But that doesn’t mean I never think about what might have been, much less what used to be. The way I feel about having once been a musician is not unlike the way some reformed alcoholics feel about booze. They know they can’t live with it anymore, but they also know how much they liked it, and they remember, as clearly as if it were this morning, how good that last drink tasted. I remember, too.

The point, of course, is that I wouldn’t have made that same choice if music had really been the most important thing in my life. Important it was, immensely so, but not that important—a near-run thing, but not quite.

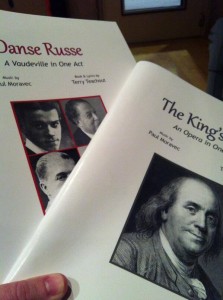

Now I’m a full-time writer, and in the past few years I’ve also transformed myself into a part-time playwright and librettist, a pursuit that has become for me what music once was, only (you might say) more so. It allows me to be creative in a way that best suits my particular talents, as well as to collaborate with other artists in much the same way that I did when I was a musician. What’s more, writing operas has put me back in touch with the working world of music, which is both a blessing and a bonus.

Now I’m a full-time writer, and in the past few years I’ve also transformed myself into a part-time playwright and librettist, a pursuit that has become for me what music once was, only (you might say) more so. It allows me to be creative in a way that best suits my particular talents, as well as to collaborate with other artists in much the same way that I did when I was a musician. What’s more, writing operas has put me back in touch with the working world of music, which is both a blessing and a bonus.

Even so, it isn’t the same as being a musician—and that part of my life, I know, is over for good. The last time I picked up a bass and tried to play it, it was as though I were wearing a pair of mittens: I still remembered where to put my hands and what to do with them, but nothing felt or sounded right. From now on I will never be anything more than a listener, a person to whom music is immensely important but not, when all is said and done, indispensable.

Even now, it still feels strange to me to make this admission, to acknowledge that my identity underwent an essential transformation somewhere along the path of my life, that I am no longer the person I was when young. Stephen Sondheim captured part of the feeling in my favorite of his songs, “The Road You Didn’t Take”: The worlds I’ll never see/Still will be around,/Won’t they?/The Ben I’ll never be,/Who remembers him? But it’s not true: I remember him very well, and sometimes I miss him very, very much.

* * *

From 2000, George Hearn sings “The Road You Didn’t Take” (from Follies) in the Stephen Sondheim revue Putting It Together: