Ira Glass stirred up a teapot tempest last week when he came home from a preview of the Public Theater’s new production of King Lear, in which John Lithgow plays the title character, and informed the world via Twitter that “Shakespeare sucks.” To which I replied, “When you tell us that Shakespeare ‘sucks,’ you’re telling us about your limitations, not his.”

It says a lot about the state of postmodern American culture that a public figure like Glass should have felt comfortable saying something like that. Time was, however, when my own limitations were almost as great as his—though even then I knew better than to suppose that Shakespeare was anything less than a supreme genius. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until well into adulthood that I could honestly claim to be other than casually familiar with more than a handful of his best-known plays.

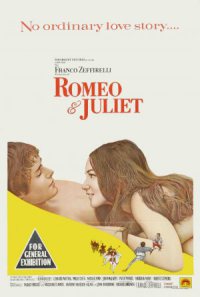

I first became aware of Shakespeare through Franco Zeffirelli’s film version of Romeo and Juliet, which I saw when it came out in 1968. It made a big impression on me, one that I suspect that had at least as much to do with the decorous nude scene (I was twelve years old and had never seen anything more revealing than a lingerie ad) as with the play itself. Be that as it may, Romeo bowled me over, and under different circumstances it might have changed my life on the spot.

I first became aware of Shakespeare through Franco Zeffirelli’s film version of Romeo and Juliet, which I saw when it came out in 1968. It made a big impression on me, one that I suspect that had at least as much to do with the decorous nude scene (I was twelve years old and had never seen anything more revealing than a lingerie ad) as with the play itself. Be that as it may, Romeo bowled me over, and under different circumstances it might have changed my life on the spot.

But Shakespeare wasn’t taught in the small-town public schools that I attended, and I didn’t have the opportunity to see any of his plays performed on stage, either, living as I did in southeast Missouri. Nor could I see them on television other than sporadically: PBS was still in its cradle, and even if it had been airing a Shakespeare play every month, it wouldn’t have mattered, since we didn’t get it in Smalltown, U.S.A. (Yes, I’m older than cable TV.) Hence my second encounter with the Bard didn’t come until two years later, when NBC telecast Richard Chamberlain’s Hallmark Hall of Fame TV version of Hamlet, and while I barely recall having watched it, I remember nothing about it. I doubt that any fourteen-year-old is ready for Hamlet.

I started reading Shakespeare in earnest in college, and I also saw Laurence Olivier’s film versions of Hamlet and Henry V and, a few years later, Kenneth Branagh’s film version of Much Ado About Nothing. Still, my most consequential post-Zeffirelli encounters with Shakespeare were with Verdi’s Otello and Falstaff and George Balanchine’s ballet version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, all of which had become vitally important to me long before I finally got around to seeing the plays on which they were based.

By then I’d moved to New York, which made it possible for me to see Shakespeare on stage more often. In 1999 I started writing a monthly column for the Washington Post about the arts in New York, and the Bard naturally figured in my reports. But it wasn’t until I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal in 2003, at the well-ripened age of forty-seven, that I finally began to see Shakespeare’s plays regularly and systematically, and to embrace them with the boundless passion of the adult convert.

It wasn’t that I didn’t already love Shakespeare. I did, very much so. But no matter how many times you’ve read King Lear or Macbeth or The Tempest, you don’t really know it until you’ve seen (and heard) it on stage. Moreover, it’s only after looking at several different stagings that you start to peel away the obscuring layers of imaginative preconception that separate you from the play itself, and realize how much Shakespeare still has to teach us about ourselves. Far from not being “relatable,” as Ira Glass claims, his plays are as true to life as…well, a This American Life piece.

As I wrote in a 2007 Journal column called “Shakespeare the Relevant”:

As I wrote in a 2007 Journal column called “Shakespeare the Relevant”:

It happens that I’ve reviewed five different productions of “Lear” since becoming the Journal’s drama critic in 2003. One was great, one very good, one dullish, one bad and one excruciatingly awful—and all were completely different. The Actors’ Shakespeare Project of Boston (that was the great one) performed “Lear” on a bare-bones set that looked as though it had been blown into the theater by a hurricane. Chicago’s Goodman Theatre (that was the awful one) turned it into a hyper-politicized parable of late capitalism whose opening scene was set in a men’s room. In between these extremes were a Mesopotamian “Lear,” a 17th-century “Lear” and an uncategorizably silly “Lear” set in what looked like the stairwell of a modern-art museum. The only thing these five productions had in common was that the same words were spoken by the actors. Yet each of them—even the awful one—was so brusquely immediate in its impact that it might have come straight off the front page of today’s tabloids.

Recall, if you will, what happens in “King Lear”: A half-senile patriarch signs away his property to a pair of greed-crazed daughters who throw him out of the house as soon as the ink dries on the deeds of trust. Stunned, he loses his mind, shortly followed by his life. Wasn’t Katie Couric telling you about that just the other day?

I’ve seen eight more Lears since then, and every one of them, good and bad alike, has enriched my understanding of the play. And while I wish I’d gotten to know Lear and Macbeth and The Tempest long before I did, it might well be that coming to Shakespeare late—and initially getting to know his work through the refracting prisms of film, music, and dance—has made it easier for me to see him plain in middle age.

Would that Ira Glass were as open to that transforming experience as I was! Fortunately, it’s never too late to learn that Shakespeare was smarter than you are, and to partake of his illimitable understanding of man’s endlessly complex nature. If he “sucks,” then so does life.

UPDATE: I received the following response to this posting on Twitter:

YOU inspired me to go to my 1st Shakespeare play, Othello (2005). Have seen 24 works (32 productions) since. Evermore thanks. You gave me a whole world. I bless you every time the house lights go down. I will always be grateful.

“I can’t tell you how touched I am to read this,” I replied. “No drama critic could ask for more.”

* * *

From Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film version of Romeo and Juliet, John McEnery performs the Queen Mab monologue:

From Verdi’s Falstaff, Tito Gobbi sings “L’onore! Ladri!” The text was adapted from Shakespeare’s Henry IV by Arrigo Boito:

From George Balanchine’s 1962 ballet version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, set to the music of Felix Mendelssohn, La Scala Ballet’s Alessandra Ferri and Camillo Di Pompo dance the Titania-Bottom pas de deux: