The last time I lived in a house was 1974. The house in question was the one in which I grew up, in which my mother lived from 1961 until her death three years ago, and in which my brother and sister-in-law now live. Since then I’ve wandered from city to city, apartment to apartment, and hotel to hotel, and the word “home,” which used to mean 713 Hickory Drive, Smalltown, U.S.A., now means…what? Wherever Mrs. T happens to be, I suppose, but it’s also true that there are other places in America to which I have developed more transient yet no less potent attachments.

The last time I lived in a house was 1974. The house in question was the one in which I grew up, in which my mother lived from 1961 until her death three years ago, and in which my brother and sister-in-law now live. Since then I’ve wandered from city to city, apartment to apartment, and hotel to hotel, and the word “home,” which used to mean 713 Hickory Drive, Smalltown, U.S.A., now means…what? Wherever Mrs. T happens to be, I suppose, but it’s also true that there are other places in America to which I have developed more transient yet no less potent attachments.

One of them is Lenox, the Massachusetts town to which I’ve gone for the past eight summers to see plays and where I spent three intense weeks in 2012 rehearsing Shakespeare & Company’s production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, my own first play. I arrived in Lenox on July 30, scarcely more than two months after my mother died, and the play opened on August 22. I spent most of the time in between sitting in a rehearsal studio, and when I wasn’t there I was mostly thinking about Satchmo. Even so, I found time to fall in love with the “deep greens and blues” of the Berkshires, the surrounding mountain range to whose beauty James Taylor paid tribute in “Sweet Baby James.” I also came to love and esteem more than a few of my newfound partners in theatrical crime—but once Satchmo opened and I hit the road again, most of them disappeared from my life. Like me, they had places to go and things to do.

That’s how theater works. It generates overwhelming emotions that melt into air each time a show closes and you move on to the next one. (This is one of the reasons why theater people so often embark on the short-lived flings that are known in the profession as “showmances.”) What seemed all-consuming and permanent turns out to have been evanescent, leaving behind nothing but yet another page in your bulging album of memories.

On Monday I returned to Lenox to spend a few days seeing shows, and I wondered how it would feel to be there after so long an absence. The answer, to my surprise, is that it felt like coming home. The mountains were as beautiful as ever, the restaurants as fine, the traffic as exasperating. (The only way to get anywhere fast in the Berkshires is to hop a ride on a fire engine.) The next night I drove over to Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, the theater where Satchmo at the Waldorf was performed, to see a new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was set in New Orleans in the Twenties. Tony Simotes, the director, said in his program note that he’d been inspired by Satchmo. It all felt as familiar as a well-worn pair of slippers…and yet it wasn’t. For I was no longer part of the company, as I had been in 2012: I was, once again, a visitor.

On Monday I returned to Lenox to spend a few days seeing shows, and I wondered how it would feel to be there after so long an absence. The answer, to my surprise, is that it felt like coming home. The mountains were as beautiful as ever, the restaurants as fine, the traffic as exasperating. (The only way to get anywhere fast in the Berkshires is to hop a ride on a fire engine.) The next night I drove over to Shakespeare & Company’s Tina Packer Playhouse, the theater where Satchmo at the Waldorf was performed, to see a new production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that was set in New Orleans in the Twenties. Tony Simotes, the director, said in his program note that he’d been inspired by Satchmo. It all felt as familiar as a well-worn pair of slippers…and yet it wasn’t. For I was no longer part of the company, as I had been in 2012: I was, once again, a visitor.

I’ve never been a clubbable person. The only club I’ve ever wanted to join is the Society of People Putting on a Show, into which I was inducted when I acted for the first time in a high-school play, an experience that I described in a memoir of my young years written after I moved to New York:

It was still me on that little stage, and everybody knew it, myself included. But something far more important happened during the six weeks we spent in rehearsal: I got my first taste of the intimacy shared by the cast and crew of a play. We spent long nighttime hours working together in a cavernous building into which no stranger was allowed to set foot. We concentrated intensely on each other on stage and talked endlessly to each other off stage, exchanging the self-conscious confidences of adolescence in the shadowy corners of the gym. After every dress rehearsal and every performance, we drove to Sambo’s, an all-night restaurant on the edge of town, and we went with faces unwashed and makeup intact, that being the badge of membership in the most exclusive fraternity in town.

I rejoined that club several more times in high school and college, then quit it for good when I graduated—or so I thought. It never occurred to me that in middle age I would start writing opera libretti and, later, a play of my own, and that through doing so I would rediscover the very special pleasure of temporarily cutting yourself off from the outside world in order to create an alternate universe of your own.

When the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo closed at the end of June, I was perforce mustered out of the Society of People Putting on a Show. Only temporarily, I hope, but for the moment I am, as theater people say, a civilian. And as I sat in the Packer Playhouse on Tuesday night, I found myself thinking of the last lines of a different Shakespeare play, Love’s Labour’s Lost, in which Adriano de Armado draws a bright line between the separate lives of actors and audience: The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way: we this way.

When the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo closed at the end of June, I was perforce mustered out of the Society of People Putting on a Show. Only temporarily, I hope, but for the moment I am, as theater people say, a civilian. And as I sat in the Packer Playhouse on Tuesday night, I found myself thinking of the last lines of a different Shakespeare play, Love’s Labour’s Lost, in which Adriano de Armado draws a bright line between the separate lives of actors and audience: The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo. You that way: we this way.

I had that line (and those lines) in mind when I wrote Louis Armstrong’s curtain speech in Satchmo at the Waldorf:

Well…Lucille’s waiting for me upstairs. Prob’ly wondering how come I took so long to get changed. Got two shows to play tomorrow, gotta take care of myself. Wanna please the people, get you a good night’s sleep. Playing that pretty music every night take a lot out of an old man.

He picks up his trumpet case.

You go that way, I go this way. And we gonna do it all over again tomorrow night. Just like always.

The opening of the All Stars’ 1954 recording of “St. Louis Blues” is heard again. The music echoes in the empty room as he exits, closing the door behind him. Blackout.

Et in Arcadia ego! But just as we cannot follow Armstrong through the dressing-room door into the darkness that swallows him up, so am I unable—for now, anyway—to return to the privileged backstage world that I briefly and ecstatically inhabited two summers ago. All I can do is watch from the aisle, seated among the civilians, wondering if I’ll ever find my way back home again by writing another play or libretto that somebody, somewhere, wants to produce.

And if I don’t? So be it. I love my day job, and I wouldn’t give it up for anything. But I also like being able on occasion to pass through the stage door, roll up my sleeves, and help make a show. I suspect that most of us, no matter how much we love our lives, long to take an occasional vacation from them. That’s mine.

* * *

James Taylor sings “Sweet Baby James” on The Johnny Cash Show in 1971:

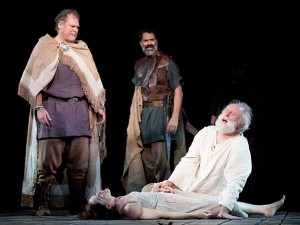

Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.

Primary among those objections is that save for being unusually tall, Mr. Lithgow is as unregal as an actor can be. He is the quintessential comic WASP, at once haughty and absurd, and he is unfailingly effective in plays in which such folk are brought low, like David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” or David Auburn’s “The Columnist.” But while “Lear” has its moments of black comedy, its anti-hero is nonetheless heroic: He is pitiful, not preposterous.