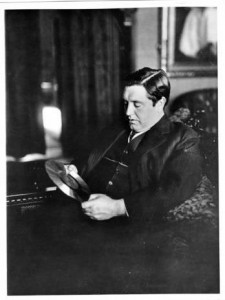

I’ve been listening to a number of John McCormack’s records of late, and thinking about the shape and significance of his great career.

Born in Ireland in 1884, McCormack quickly became one of the world’s most popular classical singers, a stylish lyric tenor with an endearing brogue and an immaculately finished vocal technique. Yet his career, unlike that of Enrico Caruso, his equally successful contemporary, was not primarily opera-based. In fact, he stopped giving staged operatic performances altogether in 1923, thereafter appearing only in recital and on radio, where he was occasionally heard on such programs as Bing Crosby’s Kraft Music Hall.

More than anything else, though, it was McCormack’s records that made him both rich and internationally famous, just as they now make it possible for us to understand precisely what kind of artist he was. Like his close friend Fritz Kreisler, who played everything from Bach and Beethoven to Irving Berlin, McCormack loved a good tune and didn’t much care who wrote it. While he favored Irish ballads, some good and some less so, the other titles in his extensive discography range from Handel’s O sleep, why dost thou leave me (which opens with a miraculously perfect trill) to Al Jolson’s Sonny Boy, with an unexpectedly generous helping of German art songs thrown in for good measure. (I especially like his 1930 performance of Hugo Wolf’s Anakreons Grab.)

More than anything else, though, it was McCormack’s records that made him both rich and internationally famous, just as they now make it possible for us to understand precisely what kind of artist he was. Like his close friend Fritz Kreisler, who played everything from Bach and Beethoven to Irving Berlin, McCormack loved a good tune and didn’t much care who wrote it. While he favored Irish ballads, some good and some less so, the other titles in his extensive discography range from Handel’s O sleep, why dost thou leave me (which opens with a miraculously perfect trill) to Al Jolson’s Sonny Boy, with an unexpectedly generous helping of German art songs thrown in for good measure. (I especially like his 1930 performance of Hugo Wolf’s Anakreons Grab.)

His recital programs hewed to a similarly wide-ranging pattern, which he described as follows:

First, I give my audiences the songs I love. Second, I give them the songs they ought to like, and will like when they hear them often enough. Third, I give them the folksongs of my native land, which I hold to be the most beautiful of any music of this kind….Fourth, I give my audiences songs they want to hear, for such songs they have every right to expect.

Accordingly, McCormack opened his concerts with two or three eighteenth-century songs and arias, usually including something by Handel. Then came Lieder, more often than not by Schubert, Brahms, or Wolf. After intermission he’d sing a few Irish folk songs, wrapping things up with a group of contemporary songs performed in English whose specific gravity varied with the nature of the occasion. (He sang two songs each by Rachmaninoff and Arnold Bax at a 1923 concert in Berlin.) The oh-me-darlin’-ma ballads with which he was so closely identified were thrown in as encores, of which his audiences always demanded plenty.

He was, in short, a middlebrow in the very best sense of the word, an artist who was at once serious and popular, who believed in his bones that those two things were not mutually contradictory, and who also believed that he could ennoble his popular audiences by introducing them to serious music. Not surprisingly, some listeners looked askance at his insistence on programming songs like Brahms’ Feldeinsamkeit side by side with (say) Ireland, Mother Ireland. W.B. Yeats, for one, was heard to mutter “If it weren’t for the damnable clarity of the words!” at a McCormack recital, while the famously fussy Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians asserted that by 1924 “he could no longer be taken altogether seriously as a musician, since in his later years he devoted his extraordinary and unimpaired gifts to largely sentimental and popular ditties.”

But even among highbrows, that was a minority opinion, as well as a demonstrably incorrect one. When McCormack died in 1945, Ernest Newman, the most ruthlessly demanding of English music critics, published this perceptive encomium to his art:

To the multitude he was the unrivalled singer of simple things expressed in a simple musical way, with a special gift for clear enunciation and clean-cut melodic line-drawing. But these gifts, admirable as they were in themselves and in his use of them, were only part of a much larger whole. He was so perfect in small things because he was steeped in greater ones, was subtly intimate with them, and had attained complete mastery of the expression of them….He was a supreme example of the art that conceals art, the sheer hard work that becomes manifest only in its results, not in the revolving of the machinery that has produced them. He never stooped to small and modest things; he invariably raised them, and with them the most sophisticated listener, to his own high level.

That is, I think, right on the mark, as can be heard by listening to McCormack’s delightful recordings of such unpretentious but winning songs as The Garden Where the Praties Grow or Off to Philadelphia or She Moved Thro’ the Fair, to all of which he brought a heartfelt yet irresistibly conversational quality that is nicely caught by Nigel Douglas: “McCormack buttonholes his listeners as if he were joking with them in his favorite pub, and the story he is telling is one that nobody in his right mind would wish to interrupt.”

Part of what Douglas is getting at, of course, is that McCormack was at bottom a balladeer—a storyteller, in other words. No matter what he sang, he turned it into a tale, and it saddens me that his splendidly communicative art should no longer be well remembered saved by antiquarians and connoisseurs, or that many of the best of his recordings are no longer easy to track down (though these two albums contain between them a very good selection of his finest work). In his day he was as popular as a rock star, and he made the finest possible use of his popularity. For that alone he deserves to be remembered.

Part of what Douglas is getting at, of course, is that McCormack was at bottom a balladeer—a storyteller, in other words. No matter what he sang, he turned it into a tale, and it saddens me that his splendidly communicative art should no longer be well remembered saved by antiquarians and connoisseurs, or that many of the best of his recordings are no longer easy to track down (though these two albums contain between them a very good selection of his finest work). In his day he was as popular as a rock star, and he made the finest possible use of his popularity. For that alone he deserves to be remembered.

Lily, his widow, found among McCormack’s papers a notebook in which he had scribbled these unutterably poignant words:

I live again the days and evenings of my long career. I dream at night of operas and concerts in which I have had my share of success. Now, like the old Irish Minstrels, I have hung up my harp because my songs are all sung.

All sung—but still there to be heard by anyone willing to make the effort to seek them out.

* * *

John McCormack and Edwin Schneider, his regular accompanist, perform “I Hear You Calling Me” on stage in the 1930 film Song o’ My Heart:

McCormack sings “Believe Me if All Those Endearing Young Charms” and “Killarney” in the 1937 film Wings of the Morning. Henry Fonda is seen briefly at the beginning of the scene: