“Three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write.”

“Three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write.”

Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

From 2004, why I don’t like to talk about the books I’m seen reading in restaurants:

From 2004, why I don’t like to talk about the books I’m seen reading in restaurants:

Even as a child, my reading habits were fairly advanced, and I got kidded mercilessly for toting around such triple-decker novels as Moby-Dick and Les Miserables. The teasing of my peers had an aggressive edge (“Hey, man, Teachout reads the encyclopedia!”), whereas my elders were merely puzzled, but the net result was to make me self-conscious whenever anyone asked what I was reading. Nearly four decades later, that question still makes me tighten up a bit, fully expecting to be razzed, and though it rarely happens nowadays, the resulting exchanges nonetheless tend to leave me feeling like a lifetime member of the awkward squad….

Read the whole thing here.

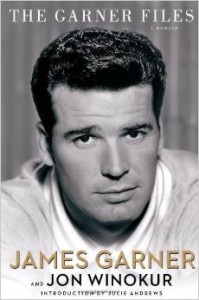

My late mother’s favorite actor, the charming and greatly loved star of Maverick and The Rockford Files, died on Saturday at the magnificent age of eighty-six. His Variety obituary reveals, among other admirable things, that he’d been married to the same woman since 1956. (Incidentally, they tied the knot sixteen days after they met.)

My late mother’s favorite actor, the charming and greatly loved star of Maverick and The Rockford Files, died on Saturday at the magnificent age of eighty-six. His Variety obituary reveals, among other admirable things, that he’d been married to the same woman since 1956. (Incidentally, they tied the knot sixteen days after they met.)

I admired Garner’s acting without reserve, and said so here in 2003. I also liked The Garner Files, his 2011 memoir, which I praised here. He didn’t make very many movies, preferring the small screen, but the finest of them are memorable, including The Americanization of Emily, The Great Escape, and Twilight, the last of which he contrived to steal right out from under Paul Newman and Gene Hackman. Best of all, though, was Burt Kennedy’s Support Your Local Sheriff!, a splendidly witty 1969 spoof western that has aged much more gracefully than the now-dated Blazing Saddles.

I plan to watch one of them this week in honor of the passing of a consummate craftsman who gave pleasure to millions of fans, myself among them.

* * *

To see a complete list of the answering-machine messages heard in the opening scenes of each episode of The Rockford Files, go here.

The theatrical trailer for Support Your Local Sheriff!:

I finally got a chance last week to see Nancy Buirski’s Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq, a documentary about the American ballerina that aired a few months ago on PBS and is now available on DVD. It’s an extraordinarily fine piece of work, in large part because it contains more than enough film of Le Clercq performing on stage and in the studio to give the viewer a clear sense of her uniquely photogenic quality.

I finally got a chance last week to see Nancy Buirski’s Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq, a documentary about the American ballerina that aired a few months ago on PBS and is now available on DVD. It’s an extraordinarily fine piece of work, in large part because it contains more than enough film of Le Clercq performing on stage and in the studio to give the viewer a clear sense of her uniquely photogenic quality.

I wrote at length about Le Clercq in All in the Dances: A Brief Life of George Balanchine:

Long-legged and long-necked to the point of gawkiness, with delicately chiseled features and a gamine smile, Tanaquil Le Clercq, known to all as “Tanny,” was a Balanchine ballet come to life. “Like a lean Giacometti, she reflected modern art,” wrote Allegra Kent, who danced with her in Balanchine’s Divertimento No. 15. Born in 1929, she was the first great dancer to have studied exclusively at the School of American Ballet, and by the time she made her professional debut in The Four Temperaments, she was fully formed. Tallchief [Maria Tallchief, Balanchine’s third wife] enviously described her as “a coltish creature who still had to grow into her long, spindly legs. Those legs went on forever—it seemed as if her body could barely sustain them. She had the long, willowy look of a fashion model, dressed stylishly in long skirts and sweaters, and had a lovely presence….Tanny didn’t have a formal education, yet she was articulate, witty, and chic.” A few of her performances were filmed, and in them one can see “the scissor legs, the vehement energy, the regal spine, the expansive upper body, the wit, the chic, the joy in movement” to which her friend Holly Brubach paid tribute after Le Clercq’s death in 2000. Jerome Robbins fell in love with her at first sight, and for a while they were all but inseparable. Balanchine teamed them to memorably comic effect in Bourrée Fantasque, while Robbins immediately began making dances of his own for her. “All the ballets I ever did for the company,” he later confessed, “it was always for Tanny.”

But Balanchine’s eye had already started to wander—as had Tallchief’s. They agreed to separate after the London season (their marriage was subsequently annulled), and no sooner did NYCB return to Manhattan than Balanchine began seeing Le Clercq in public. “I just love you to talk to, to go around with, play games, laugh like hell, etc.,” she told Robbins in a letter. “However, I’m in love with George. Maybe it’s a case of he got here first.” Devastated by what he saw as her betrayal, Robbins made The Cage, a chillingly angry portrait of a tribe of insect-women who kill the men with whom they mate. And though Tallchief remained the prima ballerina of New York City ballet for a few years more, it was Le Clercq for whom Balanchine made La Valse (1951, music by Ravel), a darkly unsettling vignette about a beautiful young girl who encounters a black-clad man at a party. He offers her a pair of black gloves into which the girl heedlessly plunges her hands. Then they waltz together with mad abandon until she collapses and dies.

La Valse ranks among Balanchine’s most strikingly personal creations, one with which Le Clercq would forever after be identified. But it was a bizarre present to offer his latest muse, whom he married at the end of 1952: a ballet in which he envisioned her premature death. What happened to her in real life would be immeasurably more shocking….

Le Clercq contracted polio in 1956, when she was just twenty-six years old. She was one of the last people in America to develop that dread disease before Jonas Salk’s vaccine made it a thing of the past. It left her paralyzed from the waist down, and she never danced again. At first Balanchine nursed her devotedly, but in due course he began to see other women, and eventually he divorced her to pursue Suzanne Farrell.

Le Clercq contracted polio in 1956, when she was just twenty-six years old. She was one of the last people in America to develop that dread disease before Jonas Salk’s vaccine made it a thing of the past. It left her paralyzed from the waist down, and she never danced again. At first Balanchine nursed her devotedly, but in due course he began to see other women, and eventually he divorced her to pursue Suzanne Farrell.

It isn’t unusual for great artists—and Tanaquil Le Clercq was a very great artist, the foremost American classical dancer of her generation—to die young. What makes her story so intensely poignant is that unlike Mozart or Keats or Robert Johnson, she lived on after tragedy struck her. A beautiful, determined woman of wit and intelligence, she managed to make an independent life for herself, and was much loved by the many friends who talk about her in Afternoon of a Faun. But there was no getting around the terrible fact that she had been deprived in youth both of her occupation, at which she was supremely gifted, and the love of her life, to whom she had been passionately devoted. I find that more haunting than I can possibly say.

In a way, it is scarcely less tragic that Le Clercq was forced to stop dancing when she did. The great dance boom of the Sixties was only a few short years away, and the next generation of Balanchine dancers, Farrell most prominent among them, would have the opportunity to appear in films and telecasts that allow later generations to see for themselves why they were so greatly admired. Not so Le Clercq, who can only be seen in a handful of kinescopes, of which this one, a 1956 CBC telecast of Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco that was released on DVD earlier this year, suggests what she was and why it mattered. So, too, does Afternoon of a Faun, which is one of the saddest and most beautiful documentaries I know.

I was born in the year that Le Clercq stopped dancing, and I never met her. But not long before she died in 2000, I happened to see her sitting in her wheelchair on the promenade of the New York State Theater, mere paces away from an enlarged photo on the wall that showed her dancing gaily with Robbins in Bourrée Fantasque. With her white hair and pale, wrinkled skin, she looked like a chic ghost. A few months later I attended her memorial service, and felt, like everyone else who came to the State Theater that dark day, that I had somehow lost a friend.

I was born in the year that Le Clercq stopped dancing, and I never met her. But not long before she died in 2000, I happened to see her sitting in her wheelchair on the promenade of the New York State Theater, mere paces away from an enlarged photo on the wall that showed her dancing gaily with Robbins in Bourrée Fantasque. With her white hair and pale, wrinkled skin, she looked like a chic ghost. A few months later I attended her memorial service, and felt, like everyone else who came to the State Theater that dark day, that I had somehow lost a friend.

* * *

The trailer for Afternoon of a Faun:

Tanaquil Le Clercq, Diana Adams, and New York City Ballet performance an excerpt from the first movement of George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, set to the music of Bach. This performance was originally telecast on the CBC in 1956, shortly before Le Clercq contracted polio and was forced to stop dancing. The first violinist heard on the soundtrack is Henryk Szeryng:

Tanaquil Le Clercq, Diana Adams, and New York City Ballet performance an excerpt from the first movement of George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, set to the music of Bach. This performance was originally telecast on the CBC in 1956, shortly before Le Clercq contracted polio and was forced to stop dancing. The first violinist heard on the soundtrack is Henryk Szeryng:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I return to the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival to catch up with its other two summer shows, The Liar and Two Gentlemen of Verona. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The acid test of a new comedy is how well it works the second time you see it. On first viewing, you’re too busy laughing to give any thought to its staying power, much less to the many ways in which the staging and performances are enhancing the effectiveness of the script. It’s for that reason that I made a point of catching the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival’s production of “The Liar,” David Ives’ rhyming “translaptation” of Pierre Corneille’s 1643 verse play about a can-you-top-this serial exaggerator (played by Jason O’Connell) who is incapable of telling the unadorned truth. When I first saw it at Chicago’s Writers’ Theatre, I came away willing to bet that it was the funniest play ever written, give or take “Noises Off.” Now that I’ve seen “The Liar” done by a different cast, I’m sure of it.

Mr. O’Connell has the perfect sense of timing that’s needed in order to sustain Mr. Ives’ comic tirades all the way to the payoff. A burly stand-up comedian turned classical actor who is blessed with a broad, expressive face, he’s equally adept at speaking verse and doing pratfalls….

Mr. O’Connell has the perfect sense of timing that’s needed in order to sustain Mr. Ives’ comic tirades all the way to the payoff. A burly stand-up comedian turned classical actor who is blessed with a broad, expressive face, he’s equally adept at speaking verse and doing pratfalls….

Eric Tucker is best known as the artistic director of Bedlam, the vest-pocket drama company whose shoestring-simple four-person productions of “Hamlet” and “Saint Joan” last season made him one of the most talked-about stage directors in New York. Now he’s making his Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival debut with “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” in which he proves to be identically and gratifyingly adept at what you might call lowbrow-highbrow comedy.

Hudson Valley goes in for high-concept stagings of Shakespeare’s comedies, and Mr. Tucker has obliged by turning “Two Gentlemen” into a “Your Show of Shows”-style parody of an Italian beach-blanket movie, with everybody dressed in the gaudiest possible Sunday-comics primary colors (bravo, Rebecca Lustig, for your million-kilowatt costumes) and accompanied by super-hip incidental music that ranges from Lana Del Rey to will.i.am. Mr. Tucker’s knack for physical comedy is so sure that the audience even kept on laughing when a thunderstorm drowned out the actors’ dialogue….

* * *

To read my review of The Liar, go here.

To read my review of Two Gentlemen of Verona, go here.

UPDATE: I mistakenly credited Christopher V. Edwards with the staging of The Liar in today’s review. In fact, the show was directed by Russell Treyz. Edwards staged the Othello that I reviewed last Friday. My humble apologies.

An ArtsJournal Blog