Charlie Haden and Horace Silver, two immensely influential jazz musicians who first came to prominence in the Fifties, died in recent weeks. I took no note of their passing in this space because it was remarked widely and well in other places, and because, to put it bluntly, it isn’t surprising that the great jazzmen of that generation should be dropping like flies. Haden, after all, was seventy-seven, Silver eighty-five. Their time had come—and gone.

Charlie Haden and Horace Silver, two immensely influential jazz musicians who first came to prominence in the Fifties, died in recent weeks. I took no note of their passing in this space because it was remarked widely and well in other places, and because, to put it bluntly, it isn’t surprising that the great jazzmen of that generation should be dropping like flies. Haden, after all, was seventy-seven, Silver eighty-five. Their time had come—and gone.

I first heard their music in the Seventies, a decade that I remember with near-perfect clarity. To the millennials, on the other hand, it is, quite literally, history. As important as Silver and Haden were, the news of their deaths cannot possibly mean to any of my young friends what it does to me, especially now that jazz is no longer a significant part of the postmodern cultural landscape.

To be sure, I’ve always spent more time thinking about the past than most people. I graduated from high school in 1974, the year of Court and Spark and Pretzel Logic and Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal. While I bought all of those albums when they came out and listened to them closely and excitedly, I was no less interested in the jazz and pop of my parents’ day. I still am.

Mrs. T thinks that I might possibly have been happier had I been born forty years earlier. Every once in a while I think she’s right. Radio Classics, one of SiriusXM’s many channels, is devoted to what fans of the genre call “old-time radio,” meaning recorded broadcasts of pre-1962 network radio series. Whenever I rent a car that has satellite radio, as I did the other day, I always set one of the buttons to “Radio Classics.” Usually it delivers up tiresome dross, but once in a while I hit the jackpot. As I drove back to Connecticut from New York last weekend, I listened to two consecutive episodes of the radio versions of Dragnet and Gunsmoke, both of which were better on radio than in their later, more widely remembered small-screen incarnations, and rejoiced at my good fortune. I wonder how many other people driving up I-95 that fine summer day were doing the same thing.

Mrs. T thinks that I might possibly have been happier had I been born forty years earlier. Every once in a while I think she’s right. Radio Classics, one of SiriusXM’s many channels, is devoted to what fans of the genre call “old-time radio,” meaning recorded broadcasts of pre-1962 network radio series. Whenever I rent a car that has satellite radio, as I did the other day, I always set one of the buttons to “Radio Classics.” Usually it delivers up tiresome dross, but once in a while I hit the jackpot. As I drove back to Connecticut from New York last weekend, I listened to two consecutive episodes of the radio versions of Dragnet and Gunsmoke, both of which were better on radio than in their later, more widely remembered small-screen incarnations, and rejoiced at my good fortune. I wonder how many other people driving up I-95 that fine summer day were doing the same thing.

Probably nobody, I can hear Mrs. T saying sharply in my mind’s ear. I expect she’s right about that, too. Nor would I care to spend more than an occasional hour on the road partaking of the purely commercial entertainment of the now-distant past. About that much my beloved wife is wrong: I would never dream of taking a one-way trip in a time machine. I don’t always rejoice in the present, but it’s where I live, and for the most part I wouldn’t have it any other way.

As I once wrote in this space:

I feel the temptation to live in the past, but one can truly live only in the moment, and the last thing I want to do is end up like the pathetic narrator of “Hey Nineteen,” the Steely Dan song about a no-longer-young baby boomer who tries to tell his teenaged girlfriend about Aretha Franklin but discovers that “she don’t remember/The Queen of Soul,” subsequently realizing that “we got nothing in common/No, we can’t talk at all.”

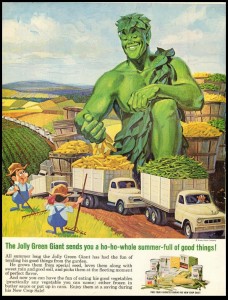

I wrote those words in 2003, very early in the life of this long-lived blog, and I stand by them eleven years later. It would be an understatement to say that I don’t like everything about the present, but I accept it. What’s more, I don’t idealize the past: I also like Twitter and texting and Pomplamoose and Justified and being able to buy really good bread at the grocery store whenever I want. I miss my mother something fierce, but I’m grateful that I’ll never to have to choke down another helping of her boiled-gray canned asparagus.

I wrote those words in 2003, very early in the life of this long-lived blog, and I stand by them eleven years later. It would be an understatement to say that I don’t like everything about the present, but I accept it. What’s more, I don’t idealize the past: I also like Twitter and texting and Pomplamoose and Justified and being able to buy really good bread at the grocery store whenever I want. I miss my mother something fierce, but I’m grateful that I’ll never to have to choke down another helping of her boiled-gray canned asparagus.

That said, I hope that my millennial friends will forgive me for my occasional lapses into the nostalgia that is surely a normal part of growing older. While my mother’s asparagus was pretty awful, Steely Dan was and is pretty damned good, and I’m glad that I grew up with songs like “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” (whose piano intro, lest we forget, was “sampled” from Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father”) and movies like Chinatown and The Godfather Part II. To accept the inescapability of the present is not to deny the pull of the past. You can have, and love, both.

As William Faulkner said in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” I know that’s true for me.

* * *

“Claustrophobia,” a 1954 episode of the original radio version of Gunsmoke, starring William Conrad as Matt Dillon: