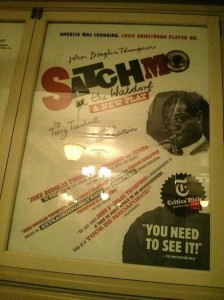

I went to see the off-Broadway production of Satchmo at the Waldorf last Friday for the first time in a month. I’m going back again next week. I expect I’ll see it two or three more times before the final performance on June 29—and that I’ll enjoy it just as much each time.

Paul Hindemith, the least pretentious artist who ever lived, would doubtless have laughed himself silly at the very thought of a playwright going to see his own show over and over again. According to the mezzo-soprano Jennie Tourel:

Hindemith, after he wrote a piece, wasn’t interested in it anymore. He never came to hear my Marienleben; although he knew I do it very well, he said he’s not interested to hear it—he’s written it.

Bernard Herrmann claimed that Alfred Hitchcock felt the same way about his films:

He runs them for people but he always leaves the room. When it says “The End” he comes back with a cigar. He says, “Why do I want to see it? I see all the things that are wrong with it. There’s nothing I can do now.”

Not me. I only got to see The Letter, my first operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec, performed three times by the Santa Fe Opera in 2009. I felt that I had to get back to my day job as a drama critic not long after The Letter opened, and I’ve regretted ever since not having taken another couple of weeks off and seeing it two or three more times.

But…why? What’s the point of seeing a show of your own repeatedly, unless you’re there to give notes to the cast and crew after the performance (which in my case scarcely ever happens) or planning to revise the script (which I don’t intend to do with Satchmo)? What do you get out of going back to see a play that you already know better than anyone else?

But…why? What’s the point of seeing a show of your own repeatedly, unless you’re there to give notes to the cast and crew after the performance (which in my case scarcely ever happens) or planning to revise the script (which I don’t intend to do with Satchmo)? What do you get out of going back to see a play that you already know better than anyone else?

I won’t deny that part of the pleasure that I take in watching Satchmo at the Waldorf is simple pride of ownership. I made this! I sometimes say to myself when the house lights go down and John Douglas Thompson walks out on stage. It’s an exhilarating sensation, one completely unlike seeing a book that you wrote in a store or on a shelf, and it doesn’t get old, at least not for me.

But this sensation, gratifying though it is, doesn’t last for very long. What I now find most interesting about seeing Satchmo, by contrast, is the way in which John’s performance, and the audience’s response to it, change from night to night. He and I talked about this process, among other things, when Marc Myers interviewed us for The Wall Street Journal last week:

“At a critical moment toward the end of the play, Armstrong shrugs off an unfortunate event and says he’ll include it in his autobiography,” said Mr. Thompson. “When we started rehearsals, I said the line as ‘I guess I’ll have to put that in the book, too,’ almost as an afterthought. Then I took out ‘have to,’ so it was more direct and emotional: ‘I guess I’ll put that in the book, too.’ It’s a self-realization that the event is an inescapable part of his legacy. Now the line is, ‘Guess…I’ll put that…in the book…too.’ It’s a bit slower and weighted, and resigned to what he must do.”

The interview appears in today’s Journal, and you can read the whole thing here. If you’re interested in how actors, writers, and directors work together to bring a play to the stage—and how they respond to the “input” of live audiences—you might want to take a look.