The off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo at the Waldorf closed yesterday afternoon at the Westside Theatre. Today I feel proud and wistful—a strange sensation. My heart is still too full to say anything more than that John Douglas Thompson, my beloved friend and colleague, outdid himself. From his opening line to his final exit, he was on fire.

This last performance, coming as it did on the heels of my receiving a Bradley Prize, has inspired me to draw up a list of other memorable “public” moments in my life to date (excluding such purely personal occasions as my wedding to Mrs. T). Perhaps not surprisingly, all but one of them have to do with art and artists:

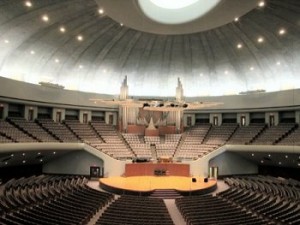

• I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds.

• I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds.

• The most spectacular performance of my short, happy life as a jazz musician was when Cat Anderson, Duke Ellington’s legendary high-note trumpeter, appeared as guest soloist with the William Jewell College Jazz Band, of which I was the regular bassist and sometime pianist. He went out with the boys in the band after the show to eat pizza and chat about life on the road. (If only I’d thought to take notes!) The rhythm section had accompanied him earlier that day on a noontime TV show. It was a live broadcast, I was playing piano, and I doubt I’ve ever been so scared as when Cat turned to me and told me to take a solo. I know my hands were shaking.

• On my first extended trip to Washington, D.C., I took a private after-hours tour of the White House (it was 1984, and an acquaintance of mine worked there). I stood behind the red velvet rope that is stretched across the door to the Oval Office when no one is home, leaning as far into the room as I dared and gaping like a schoolboy, thinking about how astonished my parents would be when I called to tell them where I’d been.

More than anything else, I remember how struck I was by the sheer unfanciness of the décor—it seemed almost homey. For all the obvious architectural elegance of the room, it reminded me more than anything else of a small-town law office writ large.

• My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote here.

• My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote here.

• I heard Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in recital at Carnegie Hall in 1988, and wrote in The Wall Street Journal about those concerts, his last public appearances in America, when he died two years ago:

He sang songs by Gustav Mahler, Schumann and Wolf, and I confess to recalling nothing specific about the performances themselves. What I do remember—indelibly—was his physical appearance. He seemed at least eight feet tall, and he strode about the stage with the energy of a very young man, all but thrusting himself at the audience. It was as if he had cast off his inhibitions and plunged into the music like a madman leaping headlong into a volcano.

• Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage.

• Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage.

What I remember most clearly about the performance itself is that Bernstein’s gestures were much more physically restrained than usual, as was often the case when he performed his own music.

• I saw the first preview of Jerome Robbins’ Broadway from the front row of New York’s Imperial Theatre in 1989. Not only was I a relative newcomer to dance, but I’d never seen a live performance of a Robbins-staged musical. This is how deep an impression it made on me: I went back four times, paying full price for my seat each time.

• I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a review of a biography of Monroe:

• I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a review of a biography of Monroe:

He stood six feet tall and looked at least seven, and his expressionless face might have been carved from a stump of petrified wood. He wore a white Stetson hat and a sky-blue suit with a pin in each lapel—one was an enamel American flag, the other an evangelical Christian emblem—and everyone in earshot called him “Mister Monroe.” Never were italics more audible.

• I was present at my friend Nancy LaMott’s last public performance in 1995. I wrote about it nine years later in the Journal:

She was wearing a wig, having lost her bottle-blonde hair to chemotherapy. Seven weeks later, she was dead. Yet her sweetly husky mezzo-soprano voice had somehow remained untouched by the terrible disease that would soon take her away from all the things for which she’d longed, and she sang as if she knew she’d never have another chance. When she was done, the Chestnut Room of New York’s Tavern on the Green exploded in rapturous applause.

The show was recorded and subsequently released on CD.

• The great Paul Cézanne retrospective came to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, its only American venue, in 1996. The Garden at Les Lauves, which normally hangs in Washington’s Phillips Collection, was the last painting in the show. Not only had I never seen it before, but I was then still largely ignorant of the visual arts. Coming upon that painting without warning, like seeing my first Balanchine ballet, changed my life forevermore in a single overwhelming stroke of perception. Seven years later, I bought my first lithograph.

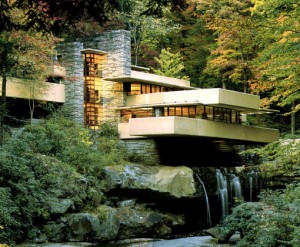

• I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it here). So began an increasingly passionate preoccupation with the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, whom I now believe to be the greatest architect of the twentieth century, leaky ceilings notwithstanding.

• I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it here). So began an increasingly passionate preoccupation with the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, whom I now believe to be the greatest architect of the twentieth century, leaky ceilings notwithstanding.

Since then I’ve slept in four of his houses, an experience that I wrote about in this 2005 Wall Street Journal piece:

To turn the key of a Wright house is to step into a parallel universe. The huge windows, the open, uncluttered floor plans, the straightforward use of such simple materials as wood, brick, concrete and rough-textured masonry: all create the illusion of a vast interior space in close harmony with its natural surroundings. Instead of walls, subtly varied ceiling heights denote the different living areas surrounding the massive fireplace that is the linchpin of every Wright house.

• I saw Alvin Epstein’s King Lear, directed by Patrick Swanson for the Actors’ Shakespeare Project, in Boston in 2005 and again in New York the following year. I’ve never seen a better performance of anything.

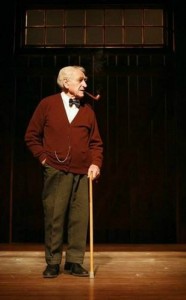

• I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged here.

• I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged here.

• If I had to pick a single night of my life as a writer and artist to stand for all the rest, it would be the opening night of the Santa Fe Opera’s production of The Letter, my first operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec, about which I blogged here.

• During my 2012 stay at Peterborough’s MacDowell Colony, about which I blogged here, here, and here, I wrote a large chunk of my Duke Ellington biography, revised Satchmo at the Waldorf, made two lasting friends, and was blissfully happy from the day I came to the day I left.

• Of Satchmo’s five opening nights to date, that one hit me hardest was the New England premiere in Lenox, Massachusetts, perhaps because the audience response was so explosive, not just at evening’s end but throughout the show. It had never before occurred to me that I might be capable of writing a play that excited people.

* * *

Excerpts from Jerome Robbins’ Broadway, shown on the 1989 Tony Awards telecast and introduced by Angela Lansbury: