In 1997 my brother and I celebrated our parents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary by planting a tree in their honor by the side of the road that runs through Smalltown’s Veterans’ Park. Ever since then, David has watched over that tree as though it were an adopted child, and he redoubled his vigilance when a terrible ice storm tore through southeast Missouri in 2009 and destroyed the maple tree that once stood in the front yard of our childhood home.

In 1997 my brother and I celebrated our parents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary by planting a tree in their honor by the side of the road that runs through Smalltown’s Veterans’ Park. Ever since then, David has watched over that tree as though it were an adopted child, and he redoubled his vigilance when a terrible ice storm tore through southeast Missouri in 2009 and destroyed the maple tree that once stood in the front yard of our childhood home.

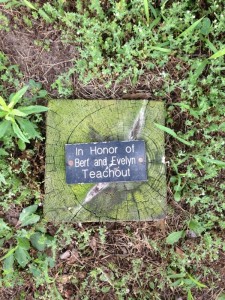

A few days ago he e-mailed me a snapshot of our parents’ tree, which is now a memorial to them. What started out as a scrawny little sapling has become something splendidly and spectacularly leafy, a tree whose best years are doubtless ahead of it but which already looks just the way it should. Magnificent it isn’t, not quite yet, but I’m willing to bet that it’ll be pretty imposing one of these days.

Both of my parents were on my mind this past weekend. Not only was Sunday Father’s Day, but Saturday—Flag Day—was my mother’s birthday. Alas, my father died mere months after we planted the tree, but my mother spent the last fifteen years of her life watching it grow. Even in its youth, she was immensely proud of “her” tree, and I took her to see it whenever I came to Smalltown. I can’t do that anymore, but I can still visit the tree in Veterans’ Park, and think about the man and woman whom it honors, and the unborn generations of men and women who, with a little bit of luck, will someday bask in its shade.

To plant a tree is by definition to invest in other people’s futures. Unless you do it when you’re very young, you almost certainly won’t live to see it reach full growth. You plant it as an act of love—and of faith. We planted that tree, and David looked after it, not merely to pay homage to our beloved parents but because both of us also love our home town, which was founded in 1860, a century and a half ago.

That’s a long time by human standards, but not by the infinite yardstick of history. As Thornton Wilder’s Stage Manager observes in Our Town:

That’s a long time by human standards, but not by the infinite yardstick of history. As Thornton Wilder’s Stage Manager observes in Our Town:

Y’know—Babylon once had two million people in it, and all we know about ’em is the names of the kings and some copies of wheat contracts…and contracts for the sale of slaves. Yet every night all those families sat down to supper, and the father came home from his work, and the smoke went up the chimney,—same as here. And even in Greece and Rome, all we know about the real life of the people is what we can piece together out of the joking poems and the comedies they wrote for the theatre back then.

So I’m going to have a copy of this play put in the cornerstone and the people a thousand years from now’ll know a few simple facts about us—more than the Treaty of Versailles and the Lindbergh flight.

That’s what my parents’ tree is: a simple fact. And if Smalltown is still around in 2060, perhaps one of its future residents will read the plaque on the ground beneath the tree and ask, Who were Bert and Evelyn Teachout, anyway? Somebody must have cared very much about them, to have planted this beautiful tree all those years ago.

Somebody—two somebodies—did. And do.