Film Forum is showing a newly restored print of William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, about which I recently wrote as part of a Commentary essay occasioned by Mark Harris’ Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War.

Film Forum is showing a newly restored print of William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, about which I recently wrote as part of a Commentary essay occasioned by Mark Harris’ Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War.

Here’s what I said about it then:

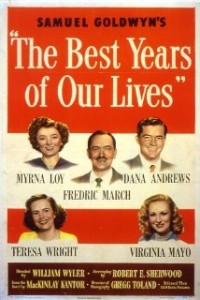

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) focuses not on the war but on its aftermath, telling the story of how three combat veterans (played by Dana Andrews, Fredric March, and Harold Russell, a real-life soldier who lost his hands in the war) adjust to civilian life. Robert Sherwood’s movingly understated screenplay incorporates some of Wyler’s personal experiences during and immediately after the war. Billy Wilder spoke for most of Hollywood in calling it “the best-directed film I’ve ever seen in my life,” though it was not, as Harris claims, the object of “unanimous” praise. In a 1947 Partisan Review essay called “The Anatomy of Falsehood” that goes unnoted in Five Came Back, Robert Warshow condemned The Best Years of Our Lives for its “optimistic picture of American life….For every difficulty, there is conceived to be some simple moral imperative that will solve it, at least to the extent that it can be solved at all.”

As usual with Warshow, there was something to his critique of The Best Years of Our Lives. The film’s fundamental weakness is that for all of its closely observed realism, it remains at bottom a Hollywood romance in which all three principal characters appear at the end to be on the way to surmounting the obstacles placed in their paths by the war. But just as none of the film’s other critics objected to these variously plausible “happy” endings, so are most present-day viewers of The Best Years of Our Lives inclined to see it not as false but impressively frank, even mature, in its presentation of the psychic and emotional effects of war.

It happens that I’d never seen The Best Years of Our Lives on a screen. Indeed, I blush to admit that it’s been at least a decade since I last saw any studio-era Hollywood film in a theater. So Mrs. T and I went down to Film Forum yesterday afternoon and caught a matinée, and were knocked sideways by the experience.

To watch The Best Years of Our Lives in a theater is, among many other things, to be riveted by Gregg Toland’s deep-focus cinematography, which is so sharply detailed that you can actually identify some of the books on the shelves of the characters’ homes. (I was amused to see, for instance, that Al and Milly Stephenson owned the once-ubiquitous two-volume Book-of-the-Month Club edition of Remembrance of Things Past.) No less riveting is Hugo Friedhofer’s Copland-influenced musical score, which comes through so clearly at Film Forum that you can easily hear the occasional portamenti played by the Louis Kaufman-led string section of the studio orchestra.

To watch The Best Years of Our Lives in a theater is, among many other things, to be riveted by Gregg Toland’s deep-focus cinematography, which is so sharply detailed that you can actually identify some of the books on the shelves of the characters’ homes. (I was amused to see, for instance, that Al and Milly Stephenson owned the once-ubiquitous two-volume Book-of-the-Month Club edition of Remembrance of Things Past.) No less riveting is Hugo Friedhofer’s Copland-influenced musical score, which comes through so clearly at Film Forum that you can easily hear the occasional portamenti played by the Louis Kaufman-led string section of the studio orchestra.

I won’t pretend, though, that I paid attention to such minutiae for more than a reel or two. I soon got caught up in the film itself, in large part for the very good reason that I was viewing it not in my living room but on the biggish screen of a darkened theater, sitting among similarly absorbed strangers. Studio-era movies were made to be seen under just those circumstances, and it is only when you see them that way that they cast their proper spell, creating an all-enveloping collective experience that can be overwhelming.

Sure enough, I was overwhelmed all over again by of The Best Years of Our Lives. What’s more, I know I wasn’t the only person in the theater who felt that way, because I heard a fair number of my neighbors weeping. Truth to tell, it’s all but impossible to watch The Best Years of Our Lives under any circumstances without weeping, but seeing it in a theater heightened the film’s emotional intensity to a pitch that at times was close to unbearable.

“Why don’t we come see old movies here more often?” I said to Mrs. T as we left the theater.

“I don’t know,” she sensibly replied. “Why don’t we?”

Of course we both knew the obvious answer to my half-rhetorical question: because it’s infinitely more convenient to watch them at home, at a time of our own choosing. But I’m glad we finally got to see The Best Years of Our Lives the way it’s supposed to be seen—the way our parents saw it—and I hope we’ll remember how much the experience meant to us the next time Film Forum announces a screening of one of our old favorites.

* * *

For more information about Film Forum’s screenings of The Best Years of Our Lives, which end on Thursday, go here.

The climactic “aircraft graveyard” scene from William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, starring Dana Andrews. The score is by Hugo Friedhofer: