I wrote a Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column earlier this year about how “serious” critics increasingly overvalue popular culture at the expense of high art. My central example was Elmore Leonard:

I wrote a Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column earlier this year about how “serious” critics increasingly overvalue popular culture at the expense of high art. My central example was Elmore Leonard:

When Elmore Leonard died in August, the papers were full of obituaries that described him as “a novelist who made crime an art.” So, at any rate, declared a headline writer for the New York Times. A year earlier, the National Book Foundation had presented Mr. Leonard with its annual medal for “distinguished contribution to American letters,” calling him a “great American author,” and the Library of America announced that it would be bringing out a three-volume edition of his work in 2014. I didn’t want to rain on his cortege, so I didn’t say what I thought, which was that he was one of the most overpraised writers of our time. A very good one, mind you—I’m a passionate fan of Mr. Leonard’s brisk, funny crime novels—but overpraised all the same.

What’s wrong with them? For one thing, they’re repetitious to a fault. I can’t count the number of Mr. Leonard’s novels that revolve around a divorced man of a certain age who falls hard for a wised-up younger woman. On the other hand, a cheeseburger is a cheeseburger. No matter how many you’ve eaten, you can usually make room for another one if it’s good, and Mr. Leonard wrote a lot of good books, “LaBrava,” “Maximum Bob” and “Tishomingo Blues” in particular.

So why grump about his obituaries? Because they exemplify a trend that has gotten out of hand. It used to be that we didn’t take popular culture seriously, but now we don’t take anything else seriously….

The problem is not that pop culture doesn’t deserve to be taken seriously. It’s that a culture totally dominated by popular art is by definition limited. Let’s go back to Elmore Leonard’s novels for a moment. Sure, they’re superbly crafted, but they’re all pure melodramas whose subject is crime, with a little romance thrown in for seasoning. So, almost without exception, are the TV series that have come of late to be widely regarded as the best that America’s storytellers have to offer. From “Hill Street Blues” to “The Sopranos” to “Breaking Bad,” these series are all thrillers of one kind or another. To be sure, they use the time-honored conventions of genre fiction to explore many other aspects of American life—but in the end, somebody always gets shot, just as a pop song, no matter how good it may be, is almost always three minutes long.

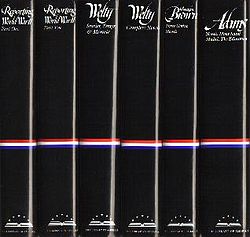

Now the Library of America has just brought out the first installment in its promised three-volume series of Leonard’s novels, which was, according to the flap copy, “prepared in consultation with the author shortly before his death.” I’ve had a fair amount to say about the Library of America over the years, most of it admiring, but I readily confess to being somewhat skeptical about the pop-culture turn that it’s been taking of late.

Allow me, if I may, to draw your attention to the mission statement that also appears on the dust jacket of Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s: “The Library of America helps to preserve our nation’s literary heritage by publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing.” To that end, it has brought out “authoritative editions” of the selected works of a remarkably wide-ranging variety of American writers, among them James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Abraham Lincoln, William Maxwell, Herman Melville, H.L. Mencken, Flannery O’Connor, Eugene O’Neill, Dawn Powell, Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Mark Twain, John Updike, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Edmund Wilson, and Richard Wright.

Allow me, if I may, to draw your attention to the mission statement that also appears on the dust jacket of Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s: “The Library of America helps to preserve our nation’s literary heritage by publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing.” To that end, it has brought out “authoritative editions” of the selected works of a remarkably wide-ranging variety of American writers, among them James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Abraham Lincoln, William Maxwell, Herman Melville, H.L. Mencken, Flannery O’Connor, Eugene O’Neill, Dawn Powell, Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Mark Twain, John Updike, Edith Wharton, Walt Whitman, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Edmund Wilson, and Richard Wright.

At the same time, though, the LOA has long made room for writers who were once thought “popular” (as Fitzgerald was, once upon a time) and are now regarded as canonical, including Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, George S. Kaufman, A.J. Liebling, and James Thurber. More recently it has brought out volumes devoted to such authors as Louisa May Alcott, Philip K. Dick, David Goodis, Jack Kerouac, H.P. Lovecraft, Barbara Tuchman, Kurt Vonnegut, and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Their publication, not surprisingly, inspired a number of online parodies, of which this one is the naughtiest.

What do I make of all this? I confess to not being altogether sure, though I should say at once that I am, in the main, an unabashed admirer of the Library of America and its high-minded mission. I have no doubt, however, that it keeps one eye firmly fixed on the bloody shirt of literary politics—and I also suspect that the growing “inclusiveness” of its list is also a function of the well-known fact that institutions, like bureaucracies, exist to perpetuate themselves. Once you’ve published the canon, what do you do next? The LOA, after all, isn’t a well-endowed art museum that can just sit there and do nothing. It’s a business, one whose editors, like everybody else in publishing, are intensely conscious of the bottom line. While their decision to admit Elmore Leonard to the canon may well be a pure act of practical criticism, I suspect there’s a teeny bit more to it than that.

What do I make of all this? I confess to not being altogether sure, though I should say at once that I am, in the main, an unabashed admirer of the Library of America and its high-minded mission. I have no doubt, however, that it keeps one eye firmly fixed on the bloody shirt of literary politics—and I also suspect that the growing “inclusiveness” of its list is also a function of the well-known fact that institutions, like bureaucracies, exist to perpetuate themselves. Once you’ve published the canon, what do you do next? The LOA, after all, isn’t a well-endowed art museum that can just sit there and do nothing. It’s a business, one whose editors, like everybody else in publishing, are intensely conscious of the bottom line. While their decision to admit Elmore Leonard to the canon may well be a pure act of practical criticism, I suspect there’s a teeny bit more to it than that.

Like I said, I haven’t yet made up my mind about Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s. It’s an evasion to quip, as I did on Twitter, that since the Library of America has published three volumes of Philip K. Dick, Leonard deserves at least as many. I’d much rather see the LOA take note of such underappreciated American novelists as (say) James Gould Cozzens, Peter DeVries, or John P. Marquand—and perhaps they will someday. But given the way in which its editors now go about their business, it makes perfect sense that they should have given pride of place to the creator of Raylan Givens. That horse left the stable a long time ago.

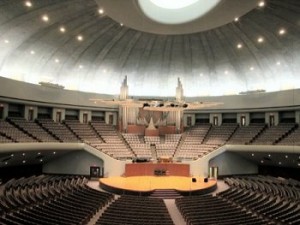

• I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds.

• I performed the Berlioz Requiem with Maurice Peress and the now-defunct Kansas City Philharmonic at Independence’s 5,800-seat RLDS Auditorium in 1975. The orchestra was augmented for the occasion by a couple of dozen college students, and I was the youngest and lowliest of the lot. Accordingly, I sat in the last chair of the bass section, at once thrilled and half-petrified. Never before or since have I heard such all-enveloping sounds. • My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote

• My first New York City Ballet performance took place in 1987. I described this life-transforming event in the opening chapter of All in the Dances, my 2004 biography of George Balanchine. You can read what I wrote  • Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage.

• Speaking of volcanoes, I only saw Leonard Bernstein in concert once, also at Carnegie Hall in 1988 (a very good year!). It was the forty-fifth anniversary of his debut with the New York Philharmonic, and he was conducting three of his own pieces, the Age of Anxiety Symphony, Chichester Psalms, and the Serenade after Plato’s Symposium. I was sitting in a box on the extreme right-hand side of the auditorium that was positioned in such a way as to give me a crystal-clear view of Bernstein standing in the wings, kissing the cufflinks that Serge Koussevitzky, his mentor, had given him (it was his customary pre-concert ritual) before coming out on stage. • I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a

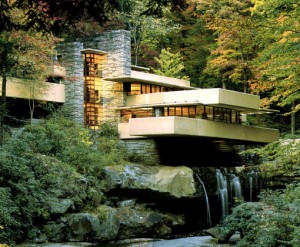

• I once saw Bill Monroe, the inventor of bluegrass, perform at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville and met him backstage after the show. Here’s how I described the experience in a  • I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it

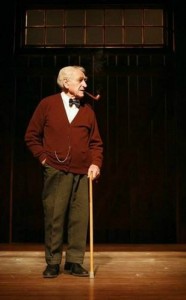

• I paid my first visit to Fallingwater in 2003 (and blogged about it  • I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged

• I also saw the eighty-six-year-old James Whitmore play the role of the Stage Manager in Our Town in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the town where Thornton Wilder’s play was written and which it is thought to depict. Mrs. T and I visited Willa Cather’s grave that same afternoon and went to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery the next day, an experience about which I blogged

•

•