“It is interesting to note that frequently actors most successfully project the thing they least are but would most like to be–to the confusion both of their loved ones and themselves.”

Simon Callow, Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu

Archives for May 2014

Lookback: is recorded sound a good thing?

From 2004:

It’s no secret, for instance, that the rise of the phonograph basically killed off domestic music-making. My grandfather, who was born a century ago, played banjo, but neither of my parents played any instrument at all, and when I started making music, it was at school, not home; I am the sole member of my extended family who not only learned a musical instrument as a child but also continued to play as an adult. What’s more, I majored in music in college, making me even less typical of my fellow baby-boomers: I have just one close friend who plays classical music on a purely amateur basis.

To be sure, I have a lot of other friends who listen to classical music, but I’m struck by how few of them go to concerts at all regularly: their participation in the culture of classical music consists mainly of buying compact discs. Indeed, I know thoroughly civilized people who actively disdain concertgoing, preferring to shovel money into the care and feeding of high-end systems. I don’t mean to knock them–they love music as much as I do–but it seems to me that there is something fundamentally parasitical about their love…

Read the whole thing here.

Almanac: Julian Bream on what musicians communicate

“As I’ve got older, I found that music for me is not just a question of music and then living; it’s become more and more a question of living and then music, with the music expressing the living. What you do, what you feel, and the actions you take, is the essence of what you communicate through music.”

Julian Bream (quoted in Tony Palmer, Julian Bream: A Life on the Road)

Here, there, and everywhere with Satchmo at the Waldorf

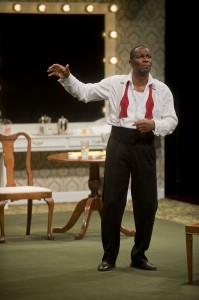

•  I rejoice to report the latest news about Satchmo at the Waldorf, which is that John Douglas Thompson just won the 2013-14 Outer Critics Circle Outstanding Solo Performance award. That is–if I do say so myself–a well-deserved honor for a great actor.

I rejoice to report the latest news about Satchmo at the Waldorf, which is that John Douglas Thompson just won the 2013-14 Outer Critics Circle Outstanding Solo Performance award. That is–if I do say so myself–a well-deserved honor for a great actor.

• Satchmo, amazingly enough, continues to be reviewed two months into its off-Broadway run. The latest notice, by Elysa Gardner, appeared last Thursday in USA Today, and like most of its predecessors, it’s a gratifyingly good one.

Here are some excerpts:

A “work of fiction, freely based on fact,” Satchmo introduces us to its subject only months before his death. Armstrong has just finished a set at the titular hotel, which has become his home and workplace; and while Thompson is (and looks) more than 20 years younger, the superb actor manages to evoke his physical and emotional weariness.

In the following 90 minutes, Thompson will also fully serve the frustration, humor and fundamental decency that come through in Teachout’s portrait of Armstrong– and, under veteran director Gordon Edelstein’s robust guidance, convey Glaser’s very different but not entirely unsympathetic nature.

First-time playwright Teachout, a veteran journalist and author, knows his stuff–his credits include the biography Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong–but spins his fact-based story with both passion and an endearing sense of whimsy.

Of course, he and Edelstein are fortunate to have Thompson. Though it would be impossible for any mere mortal to fully capture the spirit and soul of Armstrong’s music, it would be hard to imagine another trouper better equipped to give us at least a glimpse of the humanity behind it….

Read the whole thing here.

•  Even more amazingly, Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington is also still being reviewed. The Times Literary Supplement, for instance, just published a lengthy review by John Mole of the British edition. It’s not available on line, alas, but a friend sent me some excerpts:

Even more amazingly, Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington is also still being reviewed. The Times Literary Supplement, for instance, just published a lengthy review by John Mole of the British edition. It’s not available on line, alas, but a friend sent me some excerpts:

A photograph, taken in London two years after Duke Ellington’s celebrated “rebirth” at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, provides a telling frontispiece to this excellent, revelatory and, with eighty-one pages of source notes, copiously documented book. It shows the Duke regarding himself in a full-length dressing room mirror, adjusting his bow tie and–ever the model of sartorial theatricality–preparing to go out on stage to practise his familiar wry flattery, telling us that we are very beautiful, very sweet, very generous, very gracious and that he and all the kids in the band want us to know that they love us madly. On tour, he will open the show with Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the ‘A’ Train” or his own “Rockin’ in Rhythm,” introduce new work, featuring his star soloists, and reprise his greatest hits in what Terry Teachout refers to more than once as “the dreaded medley,” punctuated by the applause of recognition. This will be both the measure and the price of his achievement as composer and band leader. As Teachout forensically demonstrates, behind the smooth public face lay a complex, evasive personality…

As a drama critic for the Wall Street Journal, a playwright, an accomplished jazz bass player and a biographer of Louis Armstrong, Teachout is well placed to examine with equal authority Ellington’s methods of composition and the individual contributions of many other great musicians who brought out the unique tone colour of his orchestration. Teachout integrates his analysis with a vivid exploration of character….

Teachout gives full attention to the range of Ellington’s ambition and achievement, and the trajectory of his career….

The final chapter, which describes Ellington’s seventieth birthday celebrations at the White House and his refusal to let up on touring, as well as his loneliness and decline, is a particularly moving last act, reminding us, as so often in this book, of Terry Teachout’s ability to bring his experience of theatre to bear on the story he tells.

I especially like that last paragraph.

Just because: Julian Bream plays Malcolm Arnold

Julian Bream plays Malcolm Arnold’s Guitar Concerto in 1991, accompanied by Barry Wordsworth and the BBC Concert Orchestra:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Almanac: Julian Bream on the spirit of music

“The spirit of music can reach people who are sensitive enough to receive it in such a way that the experience is a revelation both the spiritual and the mystical. Ideally the performer has a special function, which is to bring the listener to the edge of that experience and to open the doors of this perception in such a way that those who wish to enter can.”

Julian Bream (quoted in Tony Palmer, Julian Bream: A Life on the Road)

The secret of the master

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review Westport Country Playhouse’s revival of Noël Coward’s A Song at Twilight and Second Stage’s revival of Jon Robin Baitz’s The Substance of Fire. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Rarely seen in this country since it ran on Broadway in 1974, “A Song at Twilight” was produced earlier this year on both coasts, at Hartford Stage and Pasadena Playhouse. The Hartford Stage version, directed by Mark Lamos, has now transferred to another Connecticut theater, Mr. Lamos’ own Westport Country Playhouse. Anyone who supposes that changing times have turned “A Song at Twilight” into a hoary period piece is in for a big surprise. Coward called it “far and away the best-constructed play I have ever written.” That overstates the case, but it’s definitely one of his best.

Explicitly based on the life of Somerset Maugham, “A Song at Twilight” is a portrait of Hugo Latymer (Brian Murray), a venerable novelist and sometime playwright who married his secretary (Mia Dillon) in middle age and now is wreathed in irascible respectability. Enter Carlotta (Gordana Rashovich), an angry ex-girlfriend who comes bearing a purseful of letters that Latymer sent in his indiscreet youth to the alcoholic male lover whom he dumped in order to live a straight life….

Explicitly based on the life of Somerset Maugham, “A Song at Twilight” is a portrait of Hugo Latymer (Brian Murray), a venerable novelist and sometime playwright who married his secretary (Mia Dillon) in middle age and now is wreathed in irascible respectability. Enter Carlotta (Gordana Rashovich), an angry ex-girlfriend who comes bearing a purseful of letters that Latymer sent in his indiscreet youth to the alcoholic male lover whom he dumped in order to live a straight life….

I last saw “A Song at Twilight” at the Berkshire Theater Festival in a 2008 production by Vivian Matalon, who had previously directed Coward himself in the London premiere. While that revival, which also featured Ms. Dillon, was impressive, it was accompanied by a Coward-penned curtain-raiser, a satirical playlet called “Come into the Garden, Maud” that was amusing but superfluous. “A Song at Twilight,” which runs for 90 tightly written minutes, is far more effective when presented on its own, and Mr. Lamos’ cast acts it with uncommon delicacy and poise….

Like “A Song at Twilight,” “The Substance of Fire,” directed by Trip Cullman, revolves around a cranky old litterateur, but the resemblance stops there. In “The Substance of Fire,” the irascible gentleman in question, Isaac Geldhart (John Noble), is a Holocaust survivor who escaped to America, where he started a highbrow publishing house that is now in imminent danger of bankruptcy, much to the distress of his three children (Daniel Eric Gold, Carter Hudson and Halley Feiffer), who wrest control of the stock from their father at the end of the first act.

Up to that point, “The Substance of Fire” is your standard feuding-family play, tightly packed with glib retorts, and at intermission I expected to pan it. But things get vastly more interesting when Isaac, who has retreated to his book-lined apartment and is showing signs of what appears to be fast-encroaching senility, is visited by a briskly officious social worker (Charlayne Woodard) whose task is to determine whether or not he is competent to look after himself. They, too, spend the second act sparring, but in a wholly original and absorbing way…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Refreshing a great museum

I recently visited an important Phillips Collection exhibition, Made in the U.S.A., about which I hold forth in today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When art-loving tourists think of Washington’s Phillips Collection, they usually think of Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party,” the museum’s celebrated centerpiece, or its spectacular holdings of post-Impressionist paintings by Bonnard, Cézanne and Vuillard. But Duncan Phillips, who in 1921 turned his private collection into America’s very first museum of modern art, started the Phillips (as everyone now calls it) to show his fellow countrymen that the American art he loved was good enough to stand up to direct comparison to the best work of Europe’s then-contemporary masters….

Of the 2,000 works of art in the collection at the time of his death in 1966, fully 1,400 were by American artists, and it was his custom (as it still is at the Phillips) to hang their work in close proximity to European paintings. Yet it’s been nearly 40 years since his museum last mounted a large-scale exhibition that sought to tell the story of American art as seen through the eye of its founder. Now, with “Made in the U.S.A.: American Masters from the Phillips Collection, 1850-1970,” on display through Aug. 31, the Phillips has triumphantly reasserted the validity of its original mission. By simultaneously exhibiting some 200-odd paintings, works on paper, photographs and sculptures by such artists as Alexander Calder, Stuart Davis, Richard Diebenkorn, Thomas Eakins, Helen Frankenthaler, Marsden Hartley, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, Joan Mitchell, Alfred Stieglitz and John Twachtman, the Phillips leaves no doubt that long before the postwar advent of the New York School of American painting, the U.S. had come into its own as a font of world-class art.

Of the 2,000 works of art in the collection at the time of his death in 1966, fully 1,400 were by American artists, and it was his custom (as it still is at the Phillips) to hang their work in close proximity to European paintings. Yet it’s been nearly 40 years since his museum last mounted a large-scale exhibition that sought to tell the story of American art as seen through the eye of its founder. Now, with “Made in the U.S.A.: American Masters from the Phillips Collection, 1850-1970,” on display through Aug. 31, the Phillips has triumphantly reasserted the validity of its original mission. By simultaneously exhibiting some 200-odd paintings, works on paper, photographs and sculptures by such artists as Alexander Calder, Stuart Davis, Richard Diebenkorn, Thomas Eakins, Helen Frankenthaler, Marsden Hartley, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, Joan Mitchell, Alfred Stieglitz and John Twachtman, the Phillips leaves no doubt that long before the postwar advent of the New York School of American painting, the U.S. had come into its own as a font of world-class art.

Among the plethora of first impressions evoked by the show, two in particular stand out. The first is that it is an eloquent tribute to one man’s imagination. As befits a collection assembled by an individual, it’s taste-driven, not theory-driven–and Duncan Phillips’ taste was unusually catholic….

Beyond that, though, “Made in the U.S.A.” is a model of how a museum of a certain age can renew itself–and thrill its visitors–by making bold use of its permanent collection….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.