This is the other difficult season, the time of year when every drama critic in New York is complaining about having to see too much stuff in too short a span of time. I saw three shows on consecutive days last weekend, and I’ll be going to and writing about nine Broadway shows and one off-Broadway show between now and the April 23, after which I take a train to Washington, D.C., and start my summer theater travels.

My job, of course, is to keep all of those plays and musicals straight in my head, if only for long enough to write my reviews. And it is, as I have regular occasion to say, a great job, the best one I know. But forced consumption, even of the finest art, is bad for the soul–and forced consumption of fair-to-middling art, which is what you often get on Broadway, wreaks even more psychic havoc. Years ago, when I was covering music for the Kansas City Star, I reviewed so many fair-to-middling classical concerts that something happened to me that I’d previously thought impossible: I burned out. After I gave up that line of work and moved to another city, two full years went by before I voluntarily went to another public performance of classical music.

My job, of course, is to keep all of those plays and musicals straight in my head, if only for long enough to write my reviews. And it is, as I have regular occasion to say, a great job, the best one I know. But forced consumption, even of the finest art, is bad for the soul–and forced consumption of fair-to-middling art, which is what you often get on Broadway, wreaks even more psychic havoc. Years ago, when I was covering music for the Kansas City Star, I reviewed so many fair-to-middling classical concerts that something happened to me that I’d previously thought impossible: I burned out. After I gave up that line of work and moved to another city, two full years went by before I voluntarily went to another public performance of classical music.

From then on I deliberately diversified my critical life, and the problem of burnout vanished, never again to recur. I did much the same thing a year or so after becoming the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal in 2003: I started getting out of town and reviewing regional theater. The Journal expects me to cover all Broadway openings, but otherwise I’m on my own, meaning that I pick the shows I see. That keeps me fresh–except in April, when I’m tied to the Broadway tracks.

Even then, my lot is infinitely more tolerable than that of a movie critic. I used to write a monthly column about film for Crisis, but I shut it down nine years ago. One of the reasons why I gave it up was that I’d gotten too busy doing other things, but another, equally compelling reason was that I’d discovered that new American movies no longer interested me other than occasionally. As I wrote in my valedictory column:

What makes me especially sad is that the first few years of this column (which I started writing in 1998) were a wonderful time for film in America, a time that now seems to have passed….I find myself less interested in writing about film, not because my love for the medium has diminished but because American filmmakers are now making so few movies worth seeing. These things happen in the arts–ballet and modern dance have also been going through a similarly bad patch–and rather than continue to rail against the self-evident each month, I’ve decided to till greener pastures.

Nothing that’s happened since then has made me want to resume the drudgery of seeing two or three new films each month, and it appears that a fast-growing number of my fellow Americans are coming to feel the same way.

Theater is different, if only because so much of a critic’s time on the aisle is spent watching new productions of old plays. While many American theater companies have lately grown less adventurous in choosing older plays to revive, it’s still easy enough for me to find shows that I not only want to see but, in many cases, long to see. My tentative reviewing plans for the summer, for instance, include:

• The U.S. premiere of Conor McPherson’s English-language adaptation of August Strindberg’s The Dance of Death

• An extremely rare revival of Juno, Marc Blitzstein’s musical version of Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock

• A production of The Tempest staged by Teller, with songs by Tom Waits

• A Canadian revival of J.B. Priestley’s When We Were Married, which I’ve never seen or read

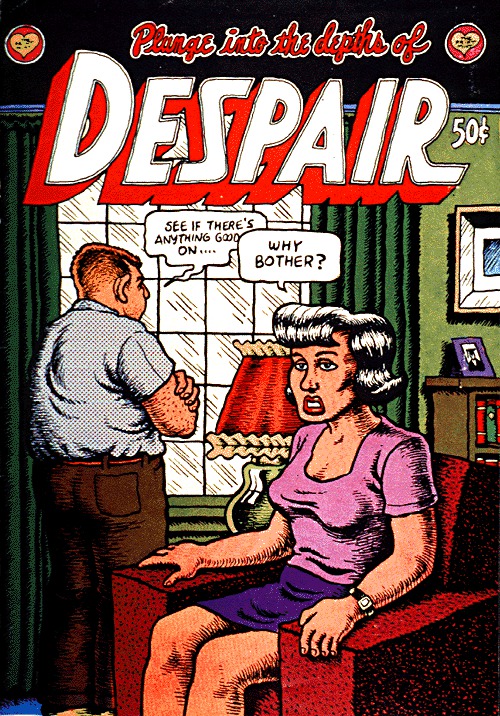

With such shows on my plate, I’ll have no trouble toughing out whatever Broadway has in store for me in the next three weeks. That said, I’m well aware of the spiritual dangers of getting stuffed up with less stimulating fare. Few things can blunt a critic’s sensibility quite so comprehensively as mediocrity. If I were only allowed to write about Broadway…well, I might go mad.

If, on the other hand, I were only allowed to write about Shakespeare, I’d do my best to remember the wise counsel of Neville Cardus, one of my favorite classical music critics. As I wrote in the Journal in 2002:

If, on the other hand, I were only allowed to write about Shakespeare, I’d do my best to remember the wise counsel of Neville Cardus, one of my favorite classical music critics. As I wrote in the Journal in 2002:

Cardus…spent World War II in Australia. Most Aussies then were well behind the cultural curve, and Cardus learned to his dismay that the centerpiece of the first concert he was to review for the Sydney Morning Herald was Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the “Mona Lisa” of classical music. What could he possibly say about a warhorse he’d heard at least a hundred times?

That night, though, he glanced around the concert hall and realized that at least half ot the audience had never before heard a performance of Beethoven’s Fifth. “To those Australians, in the Sydney Town Hall, the Fifth Symphony was a revelation,” he later recalled. “I found this a tremendous inspiration….the concert was for me an illumination and living proof that there are no hackneyed masterpieces, only hackneyed critics.”

That’s good advice–sometimes hard to take, but essential to keep in mind, just as it’s important to remember that the muse descends on her schedule, not yours. I had no idea when I went to see the new Broadway revival of A Raisin in the Sun, a familiar play that I’d already reviewed twice in the Journal, that the production would hit me as hard as it did.

C.S. Lewis said it: you must always be ready to be surprised by joy. Even on Broadway. And I am.