Not long ago I was introduced to an audience as an “intellectual.” Though I didn’t beg to differ, I entered, as I always do, a silent demurrer. To me, an intellectual is a person who is primarily interested in ideas. What I am, at least to my own way of thinking, is an aesthete, a person who is primarily interested in artistic beauty.

Not long ago I was introduced to an audience as an “intellectual.” Though I didn’t beg to differ, I entered, as I always do, a silent demurrer. To me, an intellectual is a person who is primarily interested in ideas. What I am, at least to my own way of thinking, is an aesthete, a person who is primarily interested in artistic beauty.

It’s also true, though, that I probably spend more time thinking about non-artistic ideas than your average aesthete, if there is such a thing. I just finished reading a book about Brian Friel’s plays and am about to start reading a biography of Lincoln. My impression is that most eggheads don’t jump around like that: they’re usually one thing or the other. And even within the realm of art, I range more widely afield than is typically the case. I’m as likely to be reading about (say) George Balanchine or Milton Avery or Emmanuel Chabrier as I am about a playwright, or any other kind of wordsmith.

I’ve been that way for as long as I can remember, and I understood early on that it was a peculiar way to be. What’s more, my whole life has been shaped by this peculiarity. For a long time I expected to be a musician when I grew up, but I finally figured out that while I had enough talent to pursue music as a career, it would be a mistake for me to do so. To be a successful performing musician requires a singlemindedness of artistic purpose that I’ve never had. While I loved playing music, I’m sure I would have found it frustrating to do that and nothing else, just as I found it frustrating later on when I spent a few years paying the rent by writing newspaper editorials, mostly about foreign policy. The job didn’t bore me in the least, and I think I did it pretty well, but it didn’t fulfill me, either.

After a lifetime of puzzling over this bifurcation in my nature, I’ve decided that it arises from the fact that even though I’m a fundamentally verbal person, I spent much of my youth making and thinking about music, the least verbal or representational of art forms. As Igor Stravinsky famously said in Expositions and Developments, music is “supra-personal and super-real and as such beyond verbal meanings and verbal descriptions.” He was exaggerating for effect, but at bottom he meant what he said, and I think he was more or less right.

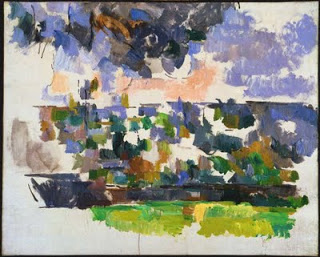

The fact that I came to music so early, and immersed myself in it so fully, undoubtedly explains why I happily embraced the other non-verbal forms of expression that I encountered later on. Abstract art and plotless dance made immediate sense to me, the same kind of sense that music had previously made. And while I get little or nothing out of the “abstract” prose of writers like Gertrude Stein, my tastes in the verbal realm also appear in some cases to bear a recognizable relationship to my musical inclinations. I tend not to care for plays of ideas–Ibsen bores me stiff–whereas I have a special liking for playwrights and filmmakers who, like Chekhov and Jean Renoir, care more about mood than plot. By the same token, I scarcely ever worry about whodunit when I read a mystery. It’s the characters and their quirks that carry me from page to page, just as my own biographies concentrate more on personality than ideas.

The fact that I came to music so early, and immersed myself in it so fully, undoubtedly explains why I happily embraced the other non-verbal forms of expression that I encountered later on. Abstract art and plotless dance made immediate sense to me, the same kind of sense that music had previously made. And while I get little or nothing out of the “abstract” prose of writers like Gertrude Stein, my tastes in the verbal realm also appear in some cases to bear a recognizable relationship to my musical inclinations. I tend not to care for plays of ideas–Ibsen bores me stiff–whereas I have a special liking for playwrights and filmmakers who, like Chekhov and Jean Renoir, care more about mood than plot. By the same token, I scarcely ever worry about whodunit when I read a mystery. It’s the characters and their quirks that carry me from page to page, just as my own biographies concentrate more on personality than ideas.

I hasten to point out that this is a general preference, not an iron disposition. I love the plays of Bertolt Brecht, for instance, and I have a more than casual interest in constitutional law, about which I’ve read far more than you’d expect of a card-carrying aesthete. But I incline as a rule to the mode of thought and feeling implied by T.S. Eliot’s remark that Henry James had “a mind so fine that no idea could violate it.” All history, especially the history of the twentieth century, argues against placing ideas in the saddle and allowing them to ride mankind. Too often they end up riding individual men and women into mass graves. As Irving Babbitt pointed out:

Robespierre and Saint-Just were ready to eliminate violently whole social strata that seemed to them to be made up of parasites and conspirators, in order that they might adjust this actual France to the Sparta of their dreams; so that the Terror was far more than is commonly realized a bucolic episode. It lends color to the assertion that has been made that the last stage of sentimentalism is homicidal mania.

That’s one of many reasons why I choose not to call myself an intellectual. “How many intellectuals have come to the revolutionary party via the path of moral indignation, only to connive ultimately at terror and autocracy?” Raymond Aron asked in The Opium of the Intellectuals (a book that John Coltrane, of all people, can be seen reading in a little-known snapshot). To be sure, musicians do tend as a group to take an innocent view of human possibility, but you rarely see them escorting anyone to the guillotine. They’re too busy trying to make everything more beautiful, one thing at a time.