“If we cannot, in the flash of a single moment, see a composition in its absolute entirety, with every pertinent detail in its proper place, we are not genuine creators.”

Paul Hindemith, A Composer’s World: Horizons and Limitations

Archives for April 2014

Bulletproof on Broadway

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review two New York openings, Bullets Over Broadway and The Heir Apparent. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

How good can a jukebox musical be? As good as “Bullets Over Broadway,” Woody Allen’s new stage version of his 1994 film, directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman (“The Producers”). The book is funny, the staging inventive, the cast outstanding, the sets and costumes satisfyingly slick. All that’s missing is a purpose-written score, in place of which we get period-true arrangements of pop songs of the ’20s and ’30s. Does that matter? It did to me–a lot–but I doubt that many other people will boggle over the absence of original songs from “Bullets Over Broadway.” Except for a flabby finale, it has the sweet scent of a box-office smash….

Ms. Stroman hasn’t rung the bell on Broadway since “Young Frankenstein,” but she remains peerless when it comes to comic choreography, and “Bullets” overflows with clever dances, including a feature for Heléne Yorke set to a 1927 double-entendre ditty called “I Want a Hot Dog for My Roll” that’s as naughty as you’d expect. Here and elsewhere, the gorgeously brassy Ms. Yorke steals the show from her better-known colleagues, but she has plenty of competition…

Ms. Stroman hasn’t rung the bell on Broadway since “Young Frankenstein,” but she remains peerless when it comes to comic choreography, and “Bullets” overflows with clever dances, including a feature for Heléne Yorke set to a 1927 double-entendre ditty called “I Want a Hot Dog for My Roll” that’s as naughty as you’d expect. Here and elsewhere, the gorgeously brassy Ms. Yorke steals the show from her better-known colleagues, but she has plenty of competition…

What about the score? Glen Kelly has written additional lyrics whose purpose is to integrate the musical sequences more smoothly into the plot, but the dramatic fit is never tight, and it doesn’t help that so many of the songs, in particular “Gee Baby, Ain’t I Good to You?” and “Up a Lazy River,” are so very familiar in their own right. Because of this, the momentum falters whenever the actors start to sing, though Ms. Stroman usually manages to get things moving again in reasonably short order….

“The Heir Apparent,” David Ives’ English-language version of Jean-François Regnard’s “Le Légataire universel,” is the latest of his brilliant “translaptations” (his word) of classic French verse comedies, in which Mr. Ives recasts the original text in briskly contemporary iambic pentameter and tinkers with the plot at will. It’s as elegantly wrought as its predecessors, “The Liar” (after Pierre Corneille’s “Le Menteur”) and “The School for Lies” (after Moliére’s “The Misanthrope”). Classic Stage Company, which brought “The School for Lies” to New York three years ago, has now done the same thing with “The Heir Apparent,” in which M. Regnard and his translaptator tell the cautionary tale of Geronte (Paxton Whitehead), a miser whose impecunious nephew (Dave Quay) endeavors by any means necessary to become his sole legatee, aided and abetted by Geronte’s scruple-free manservant (Carson Elrod). Mr. Ives’ couplets glitter with close-packed virtuosity: “That pillar of the church, that foe of whoredom,/That undisputed lord of bedroom boredom.” The cast is perfect, and John Rando’s staging is a slapsticky riot….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A scene from the original 2011 production of The Heir Apparent by the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington, D.C.:

TCM at 20

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I take note of an important cultural anniversary. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Twenty years ago next Monday, Turner Classic Movies went on the air, and the lives of film buffs were instantly improved almost beyond recognition. TCM is a basic cable channel owned by the Turner Broadcasting System that shows old movies, most of them released prior to 1970, around the clock. Some are familiar, others obscure, but all are uncut, uncolorized, uninterrupted by commercials and otherwise unaltered. No other enterprise has done more to make such films widely accessible to the general public….

I doubt I’m the only viewer who routinely flicks through the coming month’s fare and earmarks a half-dozen films at a time for future recording. I am, in short, an ardent fan–but I wonder what the future holds in store for the channel that made Robert Osborne, TCM’s host-in-chief, a star. Will it continue to prosper? Or is TCM’s business model flawed in ways that could lead to its decline and fall?

I doubt I’m the only viewer who routinely flicks through the coming month’s fare and earmarks a half-dozen films at a time for future recording. I am, in short, an ardent fan–but I wonder what the future holds in store for the channel that made Robert Osborne, TCM’s host-in-chief, a star. Will it continue to prosper? Or is TCM’s business model flawed in ways that could lead to its decline and fall?

To answer these questions, it’s necessary to reflect on the way in which TCM transformed the culture of film in America. By 1994 the VCR had made it possible for most Americans to view movies in their living rooms, but few video stores carried a wide-ranging inventory of older films, nor were they shown other than sporadically on television. If you wanted to see or study the great films of the past, you usually had to buy your own copies. Then TCM came along and changed everything, quickly became indispensable to movie lovers everywhere.

That’s still true. Most of the old movies that I watch in any given week come from TCM. But the rise of on-demand TV is changing the viewing habits of film buffs. Why wait for TCM to show “Grand Hotel” next Thursday when Amazon Instant Video will stream it to your iPad right now for $1.99?…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Almanac: Ivy Compton-Burnett on plots

“As regards plots I find real life no help at all. Real life seems to have no plots.”

Ivy Compton-Burnett, “A Conversation Between I. Compton-Burnett and M. Jourdain”

So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

• A Raisin in the Sun (drama, G/PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Rocky (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• London Wall (serious comedy, PG-13, closes Apr. 20, reviewed here)

Almanac: Edward Albee on fiction

“Fiction is fact distilled into truth.”

Edward Albee (quoted in the New York Times, Sept. 16, 1966)

Split decision

Not long ago I was introduced to an audience as an “intellectual.” Though I didn’t beg to differ, I entered, as I always do, a silent demurrer. To me, an intellectual is a person who is primarily interested in ideas. What I am, at least to my own way of thinking, is an aesthete, a person who is primarily interested in artistic beauty.

Not long ago I was introduced to an audience as an “intellectual.” Though I didn’t beg to differ, I entered, as I always do, a silent demurrer. To me, an intellectual is a person who is primarily interested in ideas. What I am, at least to my own way of thinking, is an aesthete, a person who is primarily interested in artistic beauty.

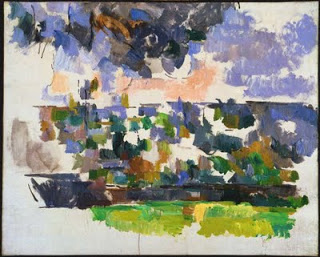

It’s also true, though, that I probably spend more time thinking about non-artistic ideas than your average aesthete, if there is such a thing. I just finished reading a book about Brian Friel’s plays and am about to start reading a biography of Lincoln. My impression is that most eggheads don’t jump around like that: they’re usually one thing or the other. And even within the realm of art, I range more widely afield than is typically the case. I’m as likely to be reading about (say) George Balanchine or Milton Avery or Emmanuel Chabrier as I am about a playwright, or any other kind of wordsmith.

I’ve been that way for as long as I can remember, and I understood early on that it was a peculiar way to be. What’s more, my whole life has been shaped by this peculiarity. For a long time I expected to be a musician when I grew up, but I finally figured out that while I had enough talent to pursue music as a career, it would be a mistake for me to do so. To be a successful performing musician requires a singlemindedness of artistic purpose that I’ve never had. While I loved playing music, I’m sure I would have found it frustrating to do that and nothing else, just as I found it frustrating later on when I spent a few years paying the rent by writing newspaper editorials, mostly about foreign policy. The job didn’t bore me in the least, and I think I did it pretty well, but it didn’t fulfill me, either.

After a lifetime of puzzling over this bifurcation in my nature, I’ve decided that it arises from the fact that even though I’m a fundamentally verbal person, I spent much of my youth making and thinking about music, the least verbal or representational of art forms. As Igor Stravinsky famously said in Expositions and Developments, music is “supra-personal and super-real and as such beyond verbal meanings and verbal descriptions.” He was exaggerating for effect, but at bottom he meant what he said, and I think he was more or less right.

The fact that I came to music so early, and immersed myself in it so fully, undoubtedly explains why I happily embraced the other non-verbal forms of expression that I encountered later on. Abstract art and plotless dance made immediate sense to me, the same kind of sense that music had previously made. And while I get little or nothing out of the “abstract” prose of writers like Gertrude Stein, my tastes in the verbal realm also appear in some cases to bear a recognizable relationship to my musical inclinations. I tend not to care for plays of ideas–Ibsen bores me stiff–whereas I have a special liking for playwrights and filmmakers who, like Chekhov and Jean Renoir, care more about mood than plot. By the same token, I scarcely ever worry about whodunit when I read a mystery. It’s the characters and their quirks that carry me from page to page, just as my own biographies concentrate more on personality than ideas.

The fact that I came to music so early, and immersed myself in it so fully, undoubtedly explains why I happily embraced the other non-verbal forms of expression that I encountered later on. Abstract art and plotless dance made immediate sense to me, the same kind of sense that music had previously made. And while I get little or nothing out of the “abstract” prose of writers like Gertrude Stein, my tastes in the verbal realm also appear in some cases to bear a recognizable relationship to my musical inclinations. I tend not to care for plays of ideas–Ibsen bores me stiff–whereas I have a special liking for playwrights and filmmakers who, like Chekhov and Jean Renoir, care more about mood than plot. By the same token, I scarcely ever worry about whodunit when I read a mystery. It’s the characters and their quirks that carry me from page to page, just as my own biographies concentrate more on personality than ideas.

I hasten to point out that this is a general preference, not an iron disposition. I love the plays of Bertolt Brecht, for instance, and I have a more than casual interest in constitutional law, about which I’ve read far more than you’d expect of a card-carrying aesthete. But I incline as a rule to the mode of thought and feeling implied by T.S. Eliot’s remark that Henry James had “a mind so fine that no idea could violate it.” All history, especially the history of the twentieth century, argues against placing ideas in the saddle and allowing them to ride mankind. Too often they end up riding individual men and women into mass graves. As Irving Babbitt pointed out:

Robespierre and Saint-Just were ready to eliminate violently whole social strata that seemed to them to be made up of parasites and conspirators, in order that they might adjust this actual France to the Sparta of their dreams; so that the Terror was far more than is commonly realized a bucolic episode. It lends color to the assertion that has been made that the last stage of sentimentalism is homicidal mania.

That’s one of many reasons why I choose not to call myself an intellectual. “How many intellectuals have come to the revolutionary party via the path of moral indignation, only to connive ultimately at terror and autocracy?” Raymond Aron asked in The Opium of the Intellectuals (a book that John Coltrane, of all people, can be seen reading in a little-known snapshot). To be sure, musicians do tend as a group to take an innocent view of human possibility, but you rarely see them escorting anyone to the guillotine. They’re too busy trying to make everything more beautiful, one thing at a time.

Snapshot: Lawrence Tibbett sings Pagliacci

From the 1935 film Metropolitan, Lawrence Tibbett sings the prologue from Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)