“The ultimate reason for his humility will be the musician’s conviction that beyond all the rational knowledge he has amassed and all his dexterity as a craftsman there is a region of visionary irrationality in which the veiled secrets of art dwell, sensed but not understood, implored but not commanded, imparting but not yielding. He cannot enter this region, he can only pray to be elected one of its messengers.”

Paul Hindemith, A Composer’s World: Horizons and Limitations

Archives for April 2014

Snapshot: Glenn Gould plays Hindemith

Glenn Gould plays the fugue from Paul Hindemith’s Third Piano Sonata:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Almanac: Paul Hindemith on composition

“The road from the head to the hand is a long one while one is still conscious of it. The man who does not so control his hand as to maintain it in unbroken contact with his thought does not know what composition is. (Nor does he whose well-routined hand runs along without any impulse or feeling behind it.”

Paul Hindemith, The Craft of Musical Composition

First time’s a charm

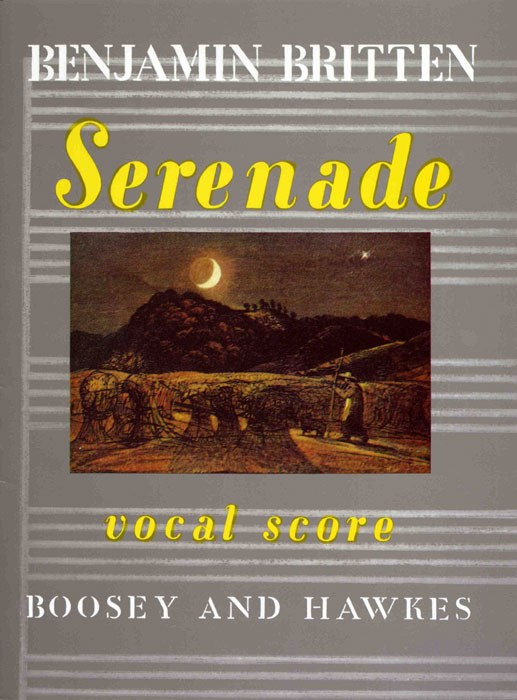

I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

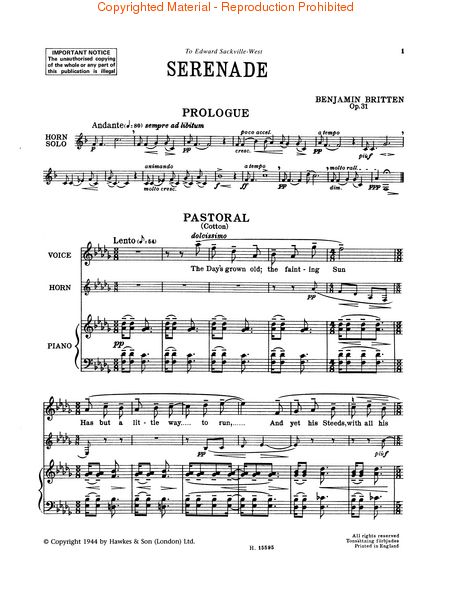

The Serenade starts off with a mysterious-sounding unaccompanied horn solo, followed by a setting of part of The Evening Quatrains, a lyric by Charles Cotton, a near-forgotten seventeenth-century English writer. Britten cut the poem in half and called his shortened version “Pastoral”:

The day’s grown old; the fainting sun

Has but a little way to run,

And yet his steeds, with all his skill,

Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

The shadows now so long do grow,

That brambles like tall cedars show;

Mole hills seem mountains, and the ant

Appears a monstrous elephant.

A very little, little flock

Shades thrice the ground that it would stock;

Whilst the small stripling following them

Appears a mighty Polypheme.

And now on benches all are sat,

In the cool air to sit and chat,

Till Phoebus, dipping in the West,

Shall lead the world the way to rest.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

“I need more chords,” Aaron Copland complained to Leonard Bernstein toward the end of his composing career. “I’ve run out of chords.” To listen to “Pastoral” is to realize that there will always be enough chords. All you have to do is know where to look.

These opening bars remind me of something that Britten said a year after he recorded the Serenade:

What is important in the arts is not the scientific part, the analyzable part of music, but the something which emerges from it but transcends it, which cannot be analyzed because it is not in it, but of it. It is the quality which cannot be acquired by simply the exercise of a technique or a system: it is something to do with personality, with gift, with spirit. I quite simply call it–magic: a quality which would appear to be by no means unacknowledged by scientists, and which I value more than any other part of music.

Back then I was still grabbing at classical music with both hands, and few weeks passed without my making a major discovery of some kind or other, most of which turned out before long to be…well, something less than major. But I was certain that my discovery of the magical “Pastoral” was more than just another passing fancy. It spoke to me, as did the rest of the Serenade, with a directness and immediacy not unlike the miraculous sensation of falling in love at first sight (something that had yet to happen to me). I knew beyond doubt that whoever Benjamin Britten was, his music would henceforth play an important part in my life–and so it did, and does.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

“Why haven’t you played this for me until now?” she asked.

“I guess I just didn’t think to,” I replied with a touch of embarrassment. “But I’m glad I finally got around to it.”

* * *

Ian Bostridge, Radovan Vlatkovic, and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra perform the prologue and “Pastoral” from Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings:

Lookback: why authors should always be modest

From 2004:

I finished my breakfast and strolled over to the neighborhood Barnes & Noble to see whether A Terry Teachout Reader was on sale yet. It wasn’t in New Non-Fiction, so I climbed the stairs to the arts section in search of something to read. There I found three copies of the Teachout Reader shelved under Jazz/Blues, meaning that no one at Barnes & Noble had bothered to look at the contents of my book. Only a year ago, I was basking in the red-carpet treatment at that very same store, including an evening reading and deluxe placement for The Skeptic: A Life of H.L. Mencken. Now I’m relegated to Jazz/Blues (though at least I got what booksellers call “face-out” placement, meaning that the front of the dust jacket is visible). As Robert Mitchum says in The Lusty Men, “Chicken today, feathers tomorrow.”…

Read the whole thing here.

Almanac: Paul Hindemith on technique

“The true work of art does not need to wrap any veil of mystery about its external features. Indeed the very hallmark of great art is that only and above the complete clarity of its technical procedure do we feel the essential mystery of its creative power.”

Paul Hindemith, The Craft of Musical Composition

Inner direction

Apropos of the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo at the Waldorf, Laura Lippman recently said something that caught my eye: “I think you have to have such confidence to be a theatre critic and write a play. He’s really opened himself up.”

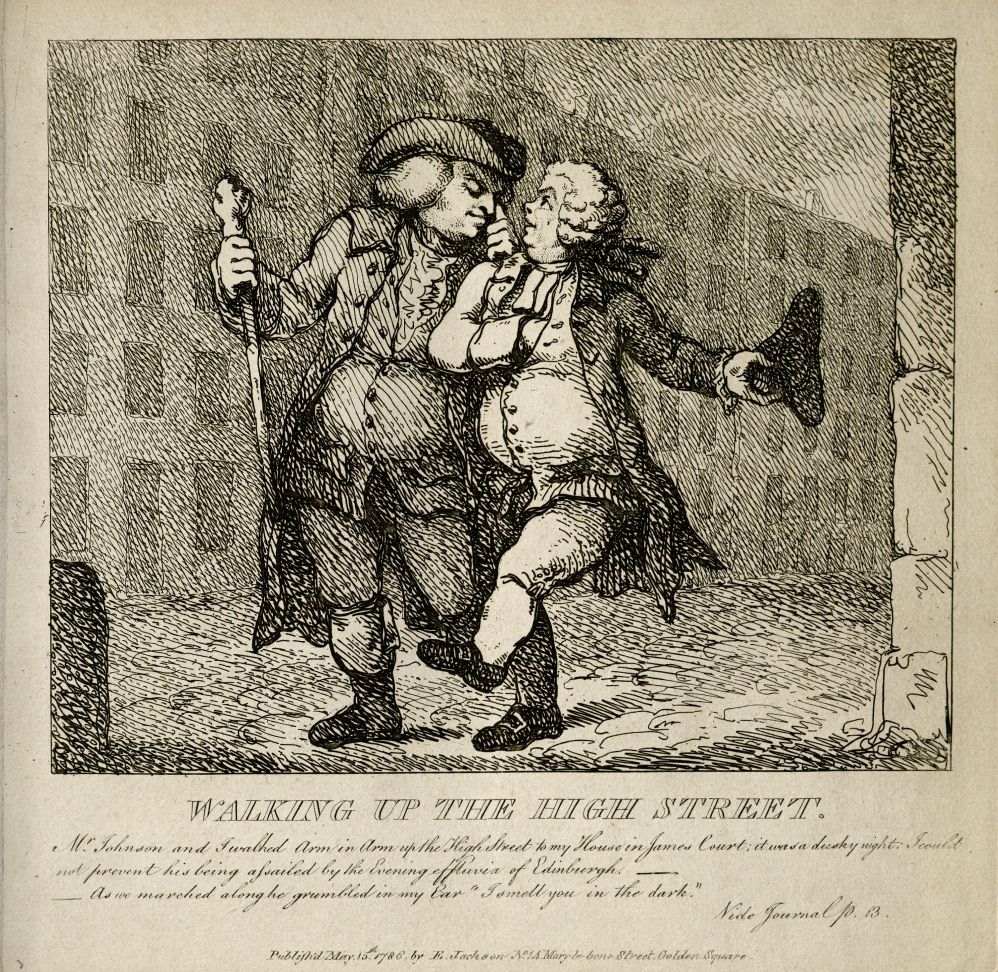

This reminds me of an oft-quoted passage from Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

This reminds me of an oft-quoted passage from Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

His tutor, Mr. Jorden, fellow of Pembroke, was not, it seems, a man of such abilities as we should conceive requisite for the instructor of Samuel Johnson, who gave me the following account of him. “He was a very worthy man, but a heavy man, and I did not profit much by his instructions. Indeed, I did not attend him much. The first day after I came to college I waited upon him, and then staid away four. On the sixth, Mr. Jorden asked me why I had not attended. I answered I had been sliding in Christ-Church meadow. And this I said with as much nonchalance as I am now talking to you. I had no notion that I was wrong or irreverent to my tutor.” BOSWELL: “That, Sir, was great fortitude of mind.” JOHNSON: “No, Sir; stark insensibility.”

As it happens, I did give some thought to what Laura said in the weeks and months before The Letter, my first operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec, opened in Santa Fe in 2009. In fact, I wrote a piece about it for the Los Angeles Times in which I pointed out that “I’m submitting myself for approval–not just from my fellow critics but from the people who read my reviews each week” and admitted to finding the experience “both terrifying and exhilarating. I’ve never set foot inside a casino, but I can’t help but think that this must be what it feels like to place a big bet.”

That, however, was strictly retrospective, at least as regards my colleagues. It simply didn’t occur to me to think about what the critics would say about The Letter while I was writing it, much less to suppose that it was somehow courageous of me to offer myself up to them as a potential target. Nor did I think about it at all with regard to Satchmo at the Waldorf before the show came to New York–and that was solely because I knew that the reviews of Satchmo would necessarily have an effect on the length of its run. Until that finally became an issue, I never thought about them at all.

The truth is that I rarely spend much time thinking about what other people think of me. Of course I want my friends to like me, and I try to conduct myself in such a way as to earn their liking and their trust. But when it comes to my work, my internal compass was set long ago, and whether or not it’s accurate, I don’t feel that I have much choice in middle age but to follow it. I think what I think, and I trust my eye and ear. Were it otherwise, I couldn’t function: I’d always be second-guessing myself.

This doesn’t mean that I didn’t take the counsel of my collaborators on Satchmo at the Waldorf with the utmost seriousness, just as I take very seriously the suggestions of my editors at The Wall Street Journal, Commentary, and elsewhere. When it came to Satchmo, I knew that I was doing something that was new to me, and that I’d be a fool not to listen closely to the experienced professionals with whom I had the good fortune to collaborate, and do what they suggested if it made sense to me (which it usually did).

When it comes to reviews, on the other hand, I try to take the advice that I give to others, which is the same advice given by André Previn in No Minor Chords: “It is perfectly correct to disregard all the bad reviews one gets, but only if at the same time, one disregards the good ones as well.” As Dr. Johnson told Boswell on another occasion, there’s an end on’t. Sure, I love getting good reviews, but I do my best not to take them to heart. As for the pans, of which I’ve gotten my share over the years, I ignore them. Either way, nobody has ever said anything about me in print, good or bad, that I can quote from memory. (You might be surprised to know how many artists can rattle off a perfectly remembered phrase from a bad review that came out a decade ago.)

When it comes to reviews, on the other hand, I try to take the advice that I give to others, which is the same advice given by André Previn in No Minor Chords: “It is perfectly correct to disregard all the bad reviews one gets, but only if at the same time, one disregards the good ones as well.” As Dr. Johnson told Boswell on another occasion, there’s an end on’t. Sure, I love getting good reviews, but I do my best not to take them to heart. As for the pans, of which I’ve gotten my share over the years, I ignore them. Either way, nobody has ever said anything about me in print, good or bad, that I can quote from memory. (You might be surprised to know how many artists can rattle off a perfectly remembered phrase from a bad review that came out a decade ago.)

David Mamet, I gather, takes his reviews way too seriously, though he’s capable (or was) of being funny about it. When New York held a “Best of Anything” contest back in the Eighties, he entered the following as “Best Review”: “I never understood the theater until this night. Please excuse everything I’ve ever written. When you read this, I’ll be dead. Signed, Clive Barnes.” That made me laugh out loud when I first read it, and it still makes me smile. Even so, I’ve never felt that way about a critic–not yet, anyway.

One last remark from the ever-relevant Dr. Johnson: “It is advantageous to an author that his book should be attacked as well as praised. Fame is a shuttlecock. If it be struck only at one end of the room, it will soon fall to the ground. To keep it up, it must be struck at both ends.” Anybody who gets reviewed should keep that wise counsel firmly in mind.

Just because: Paul Hindemith conducts Brahms

Paul Hindemith conducts the Chicago Symphony in a 1963 performance of Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)