Apropos of the off-Broadway transfer of Satchmo at the Waldorf, Laura Lippman recently said something that caught my eye: “I think you have to have such confidence to be a theatre critic and write a play. He’s really opened himself up.”

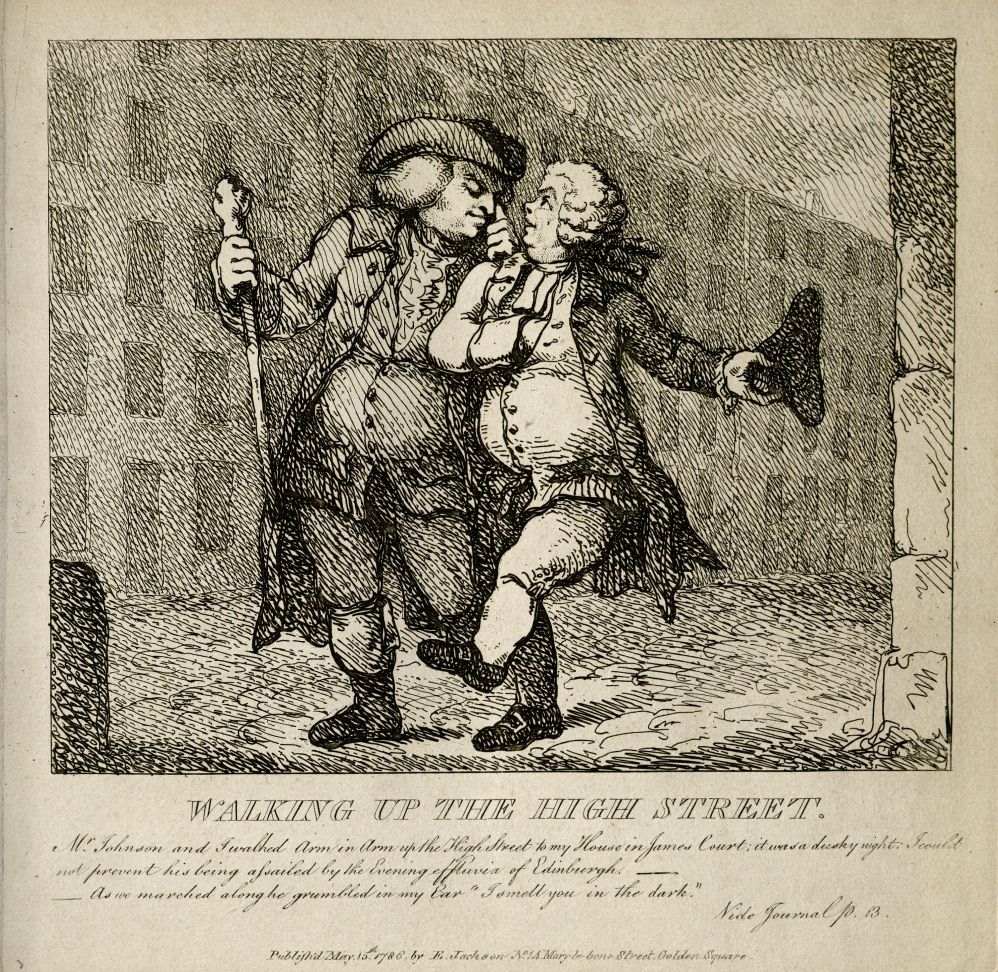

This reminds me of an oft-quoted passage from Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

This reminds me of an oft-quoted passage from Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

His tutor, Mr. Jorden, fellow of Pembroke, was not, it seems, a man of such abilities as we should conceive requisite for the instructor of Samuel Johnson, who gave me the following account of him. “He was a very worthy man, but a heavy man, and I did not profit much by his instructions. Indeed, I did not attend him much. The first day after I came to college I waited upon him, and then staid away four. On the sixth, Mr. Jorden asked me why I had not attended. I answered I had been sliding in Christ-Church meadow. And this I said with as much nonchalance as I am now talking to you. I had no notion that I was wrong or irreverent to my tutor.” BOSWELL: “That, Sir, was great fortitude of mind.” JOHNSON: “No, Sir; stark insensibility.”

As it happens, I did give some thought to what Laura said in the weeks and months before The Letter, my first operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec, opened in Santa Fe in 2009. In fact, I wrote a piece about it for the Los Angeles Times in which I pointed out that “I’m submitting myself for approval–not just from my fellow critics but from the people who read my reviews each week” and admitted to finding the experience “both terrifying and exhilarating. I’ve never set foot inside a casino, but I can’t help but think that this must be what it feels like to place a big bet.”

That, however, was strictly retrospective, at least as regards my colleagues. It simply didn’t occur to me to think about what the critics would say about The Letter while I was writing it, much less to suppose that it was somehow courageous of me to offer myself up to them as a potential target. Nor did I think about it at all with regard to Satchmo at the Waldorf before the show came to New York–and that was solely because I knew that the reviews of Satchmo would necessarily have an effect on the length of its run. Until that finally became an issue, I never thought about them at all.

The truth is that I rarely spend much time thinking about what other people think of me. Of course I want my friends to like me, and I try to conduct myself in such a way as to earn their liking and their trust. But when it comes to my work, my internal compass was set long ago, and whether or not it’s accurate, I don’t feel that I have much choice in middle age but to follow it. I think what I think, and I trust my eye and ear. Were it otherwise, I couldn’t function: I’d always be second-guessing myself.

This doesn’t mean that I didn’t take the counsel of my collaborators on Satchmo at the Waldorf with the utmost seriousness, just as I take very seriously the suggestions of my editors at The Wall Street Journal, Commentary, and elsewhere. When it came to Satchmo, I knew that I was doing something that was new to me, and that I’d be a fool not to listen closely to the experienced professionals with whom I had the good fortune to collaborate, and do what they suggested if it made sense to me (which it usually did).

When it comes to reviews, on the other hand, I try to take the advice that I give to others, which is the same advice given by André Previn in No Minor Chords: “It is perfectly correct to disregard all the bad reviews one gets, but only if at the same time, one disregards the good ones as well.” As Dr. Johnson told Boswell on another occasion, there’s an end on’t. Sure, I love getting good reviews, but I do my best not to take them to heart. As for the pans, of which I’ve gotten my share over the years, I ignore them. Either way, nobody has ever said anything about me in print, good or bad, that I can quote from memory. (You might be surprised to know how many artists can rattle off a perfectly remembered phrase from a bad review that came out a decade ago.)

When it comes to reviews, on the other hand, I try to take the advice that I give to others, which is the same advice given by André Previn in No Minor Chords: “It is perfectly correct to disregard all the bad reviews one gets, but only if at the same time, one disregards the good ones as well.” As Dr. Johnson told Boswell on another occasion, there’s an end on’t. Sure, I love getting good reviews, but I do my best not to take them to heart. As for the pans, of which I’ve gotten my share over the years, I ignore them. Either way, nobody has ever said anything about me in print, good or bad, that I can quote from memory. (You might be surprised to know how many artists can rattle off a perfectly remembered phrase from a bad review that came out a decade ago.)

David Mamet, I gather, takes his reviews way too seriously, though he’s capable (or was) of being funny about it. When New York held a “Best of Anything” contest back in the Eighties, he entered the following as “Best Review”: “I never understood the theater until this night. Please excuse everything I’ve ever written. When you read this, I’ll be dead. Signed, Clive Barnes.” That made me laugh out loud when I first read it, and it still makes me smile. Even so, I’ve never felt that way about a critic–not yet, anyway.

One last remark from the ever-relevant Dr. Johnson: “It is advantageous to an author that his book should be attacked as well as praised. Fame is a shuttlecock. If it be struck only at one end of the room, it will soon fall to the ground. To keep it up, it must be struck at both ends.” Anybody who gets reviewed should keep that wise counsel firmly in mind.