I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

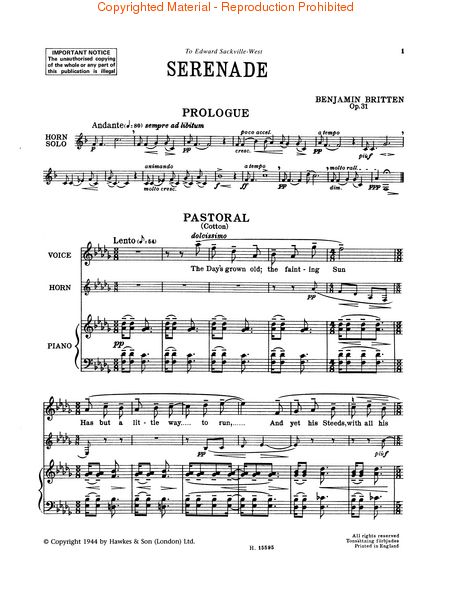

The Serenade starts off with a mysterious-sounding unaccompanied horn solo, followed by a setting of part of The Evening Quatrains, a lyric by Charles Cotton, a near-forgotten seventeenth-century English writer. Britten cut the poem in half and called his shortened version “Pastoral”:

The day’s grown old; the fainting sun

Has but a little way to run,

And yet his steeds, with all his skill,

Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

The shadows now so long do grow,

That brambles like tall cedars show;

Mole hills seem mountains, and the ant

Appears a monstrous elephant.

A very little, little flock

Shades thrice the ground that it would stock;

Whilst the small stripling following them

Appears a mighty Polypheme.

And now on benches all are sat,

In the cool air to sit and chat,

Till Phoebus, dipping in the West,

Shall lead the world the way to rest.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

“I need more chords,” Aaron Copland complained to Leonard Bernstein toward the end of his composing career. “I’ve run out of chords.” To listen to “Pastoral” is to realize that there will always be enough chords. All you have to do is know where to look.

These opening bars remind me of something that Britten said a year after he recorded the Serenade:

What is important in the arts is not the scientific part, the analyzable part of music, but the something which emerges from it but transcends it, which cannot be analyzed because it is not in it, but of it. It is the quality which cannot be acquired by simply the exercise of a technique or a system: it is something to do with personality, with gift, with spirit. I quite simply call it–magic: a quality which would appear to be by no means unacknowledged by scientists, and which I value more than any other part of music.

Back then I was still grabbing at classical music with both hands, and few weeks passed without my making a major discovery of some kind or other, most of which turned out before long to be…well, something less than major. But I was certain that my discovery of the magical “Pastoral” was more than just another passing fancy. It spoke to me, as did the rest of the Serenade, with a directness and immediacy not unlike the miraculous sensation of falling in love at first sight (something that had yet to happen to me). I knew beyond doubt that whoever Benjamin Britten was, his music would henceforth play an important part in my life–and so it did, and does.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

“Why haven’t you played this for me until now?” she asked.

“I guess I just didn’t think to,” I replied with a touch of embarrassment. “But I’m glad I finally got around to it.”

* * *

Ian Bostridge, Radovan Vlatkovic, and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra perform the prologue and “Pastoral” from Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings: