Alec Wilder, The Octets 1938-47: Music for Lost Souls and Wounded Birds (Hep, two CDs). The first CD reissue ever of the complete recordings of the Alec Wilder Octet, a studio-only ensemble that played instrumental miniatures in which Wilder fused jazz and classical music to utterly original and winsome effect. The forty-five tracks on this set also include contemporary recordings by other performers and ensembles, among them a group of Wilder-penned chamber-orchestra pieces conducted by none other than Frank Sinatra. I wrote the liner notes, which put the octet’s recordings in historical perspective (TT).

Archives for March 2014

CD

See us! Hear us!

I have only one piece of news about Satchmo at the Waldorf today, but it’s a nifty one: John Douglas Thompson and I were the guests on this week’s edition of Theater Talk. We chatted at length about the play with Susan Haskins and Michael Riedel, who asked smart questions, let us answer them fully, and edited the resulting tape so skillfully that we came off sounding…well, reasonably sensible.

Our appearance on the show can now be viewed online. I hope you find it interesting:

Fugitive thoughts of an overextended drama critic

The New York theater season is hurtling toward its annual climax. As of this morning, I have thirteen more shows to see between now and April 24, when Cabaret opens and the Tony Awards eligibility period comes to an end. Some I long to see, others I dread, but even if I had good reason to expect them all to be terrific, that would still be too damn much theater.

It is, however, my job to be as receptive as possible to each show, and I take that job quite seriously indeed. On Tuesday I paid a visit to Yale’s Morse College (designed by Eero Saarinen, thank you very much!) and spoke to two wonderfully receptive groups of students about my work as a critic and playwright. One of the things that I told them was that I try to empty my mind of all preconceptions about a show just before the curtain goes up, and that I have no doubt of my ability to do so.

It is, however, my job to be as receptive as possible to each show, and I take that job quite seriously indeed. On Tuesday I paid a visit to Yale’s Morse College (designed by Eero Saarinen, thank you very much!) and spoke to two wonderfully receptive groups of students about my work as a critic and playwright. One of the things that I told them was that I try to empty my mind of all preconceptions about a show just before the curtain goes up, and that I have no doubt of my ability to do so.

How can I know this? Because after eleven years at The Wall Street Journal, I’m still capable of being surprised by the excellence of a show that I expected to dislike.

I walked into the theater earlier this month fully planning on panning Rocky and Les Misérables, and ended up writing–much to my surprise–favorable reviews. In the latter case I was so surprised that I actually leaned over to my companion for the evening ten minutes into the performance and whispered, “I can’t believe I’m actually going to be writing a good review of Les Miz!” That’s how I know I’m seeing the show on stage, not the one in my head.

The trouble with all this nonstop theatergoing, of course, is that it leaves me with little time to do anything else. I saw two shows and wrote three pieces last week. I’ll be seeing four shows and writing one piece this week. When I’m not thinking about other people’s shows, I’m thinking about my own show. That’s not the way I like to live.

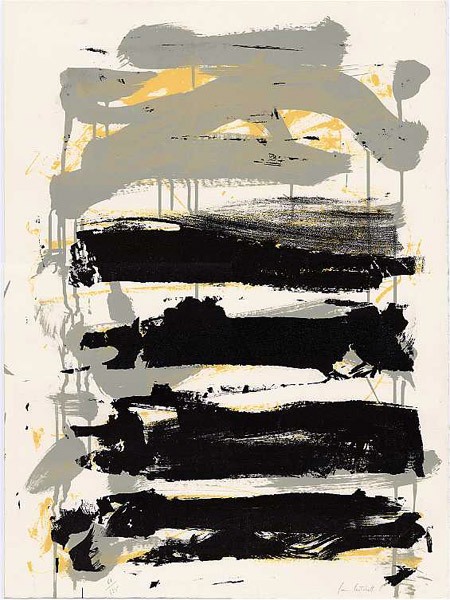

Fortunately, I have enough spare time to read about other things, even if I can’t actually do any of them. I’ve also been managing to listen to a fair amount of music, mostly classical, on the side. Yesterday I made time to listen to Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Concerto Accademico and Malcolm Arnold’s Two-Violin Concerto, for instance, neither of which had anything obvious to do with my stage-related duties. I also reread Alison Bechtel’s Fun Home and My Happy Life, Darius Milhaud’s delightful memoir, which has put me in the mood to listen to some of his life-enhancingly sunny music as well. And though I’m too overcommitted to cram in a visit to a museum or gallery, it’s my great good fortune to live with a couple of dozen pieces of modern art (the one pictured here is “Composition Jaune/Grise,” a 1990 lithograph by Joan Mitchell) whose presence in the apartment does much to keep me on an even keel.

Fortunately, I have enough spare time to read about other things, even if I can’t actually do any of them. I’ve also been managing to listen to a fair amount of music, mostly classical, on the side. Yesterday I made time to listen to Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Concerto Accademico and Malcolm Arnold’s Two-Violin Concerto, for instance, neither of which had anything obvious to do with my stage-related duties. I also reread Alison Bechtel’s Fun Home and My Happy Life, Darius Milhaud’s delightful memoir, which has put me in the mood to listen to some of his life-enhancingly sunny music as well. And though I’m too overcommitted to cram in a visit to a museum or gallery, it’s my great good fortune to live with a couple of dozen pieces of modern art (the one pictured here is “Composition Jaune/Grise,” a 1990 lithograph by Joan Mitchell) whose presence in the apartment does much to keep me on an even keel.

So yes, I’m coping–just about. But I long vainly for just a bit more of that precious commodity to which Asegai, one of the characters in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, whose second Broadway revival I saw on Saturday, refers with dry amusement: “Don’t get up. Just sit a while and think. Never be afraid to sit a while and think.” If only I could.

Just because: Darius Milhaud’s Scaramouche

Andrea Lucchesini and Pietro De Maria play “Brasiliera,” the finale of Darius Milhaud’s Scaramouche, at a 2005 concert:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Almanac: Britten and Shostakovich on Puccini

“Later, they became firm friends when Ben visited Russia, and I enjoyed the producer Colin Graham’s account of an exchange between the two. Shostakovich: ‘What do you think of Puccini?’ Britten: ‘I think his operas are dreadful!’ Shostakovich: ‘No, Ben, you are wrong. He wrote marvellous operas, but dreadful music!'”

The Tongs and the Bones: The Memoirs of Lord Harewood

Fathers know best

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review two Broadway shows, Terrence McNally’s Mothers and Sons and the new revival of Les Misérables. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

At 75, Terrence McNally has seen the best–and worst–of it. He’s a member of the generation of gay men who survived the AIDS epidemic and lived long enough to marry their partners (as Mr. McNally himself did four years ago). In 1990 he wrote an Emmy-winning PBS teleplay called “Andre’s Mother” about an angry mother whose son died of AIDS. Now he’s returned to the subject with “Mothers and Sons,” a stage play set 20 years later in which we once again meet Katharine (Tyne Daly), Andre’s mother, and Cal (Frederick Weller), his lover, who has since wed Will (Bobby Steggert), a younger man with whom he has a six-year-old son, Bud (Grayson Taylor).

That’s a big and fertile subject, and it’s not hard to see why Mr. McNally might have had trouble writing about it with the emotional distance necessary to turn feeling into art. But he evidently lacks that distance, and the result is a play that is by turns glib, smug, preachy, sentimental and, for about 10 minutes of its hour-and-a-half span, quite moving.

The glibness is the worst part. The first hour of “Mothers and Sons,” a punchline-heavy depiction of Katharine’s awkward reunion with Cal, rattles on far too easily. As for the smugness, it comes to the fore whenever Katharine, who grew up in a declassé New York suburb, married a Texan and moved with him to Dallas, opens her mouth….

The glibness is the worst part. The first hour of “Mothers and Sons,” a punchline-heavy depiction of Katharine’s awkward reunion with Cal, rattles on far too easily. As for the smugness, it comes to the fore whenever Katharine, who grew up in a declassé New York suburb, married a Texan and moved with him to Dallas, opens her mouth….

I don’t doubt that Mr. McNally has made what he believes to be a good-faith effort to give Katharine her due, or that the world is full of aging women who continue to bristle at the very thought of homosexuality. To turn this one into a stage villainess, though, is to pick off a slow-moving target….

“Les Misérables,” which opened on Broadway in 1987 and ran there until 2003, was revived three years later in a cut-down version of the original staging that had a 463-performance run. Now it’s back on Broadway, this time in a completely new production that is widely expected to attract fans of the 2012 film version. It seems a safe bet that it’ll do so, and if, like me, you don’t care for “Les Miz,” you’ll have trouble thinking of any other reason to revive it for the second time in a decade. So grab your brim and hold on tight: The new version, directed by Laurence Connor and James Powell, is one of the strongest musical-comedy productions to hit town in years. It doesn’t make the show any better, but it’s so exciting that you might want to go anyway….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The man who did too much

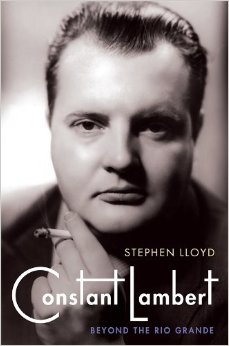

Constant Lambert, about whom I’ve written more than once in this space and elsewhere, is the subject of an important new primary-source biography, which is in turn the subject of my “Sightings” column in today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If you’ve read “A Dance to the Music of Time,” Anthony Powell’s cycle of 12 novels about England in the 20th century, you’ll likely recognize the name of Hugh Moreland. A hugely talented, deeply troubled conductor-composer-wit who “gravitated from one hopeless love affair to another,” Moreland is one of Powell’s most indelibly drawn characters, so much so that it’s no surprise to learn that he was drawn from life. He was based on Constant Lambert, one of Powell’s closest friends, an even more talented conductor-composer-wit who died in 1951, two days before his 46th birthday, his health shattered by diabetes and drink. Unlike his fictional counterpart, who never quite manages to break into the top tier of anything, Lambert was a major figure in English musical life throughout the ’30s and ’40s. Alas, his reputation faded quickly after his death, and today he is mainly remembered by scholars and specialists. Indeed, more people now know him as the model for Moreland than for anything he did, said or wrote in real life.

It’s inordinately difficult to resuscitate such lost souls, but Stephen Lloyd gives it his very best shot in “Constant Lambert: Beyond the Rio Grande,” a 622-page biography published this month by Boydell Press that’s as close to definitive as a biography can be. Mr. Lloyd gets absolutely everything right, including the gossip (among other exotic things, Lambert was a longtime lover of Dame Margot Fonteyn, the celebrated English ballerina) and the dirty limericks (he wrote some of the funniest ones ever, none of them printable here). Far more important, Mr. Lloyd makes a compelling case for Lambert’s continuing significance. He was a powerfully individual composer, an amazingly talented conductor and one of the most quotable critics ever to put pen to paper.

It’s inordinately difficult to resuscitate such lost souls, but Stephen Lloyd gives it his very best shot in “Constant Lambert: Beyond the Rio Grande,” a 622-page biography published this month by Boydell Press that’s as close to definitive as a biography can be. Mr. Lloyd gets absolutely everything right, including the gossip (among other exotic things, Lambert was a longtime lover of Dame Margot Fonteyn, the celebrated English ballerina) and the dirty limericks (he wrote some of the funniest ones ever, none of them printable here). Far more important, Mr. Lloyd makes a compelling case for Lambert’s continuing significance. He was a powerfully individual composer, an amazingly talented conductor and one of the most quotable critics ever to put pen to paper.

So why haven’t you heard of him?

In addition to dying too young to consolidate his reputation, Lambert complicated posterity’s job by deliberately choosing not to specialize in a single line of creative endeavor. Even within his chosen fields, his interests ranged so widely and unpredictably that it was all but impossible to pin him down….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

To read the complete text of Lambert’s Music Ho! on line, go here.

André Previn leads the London Madrigal Singers and the London Symphony in a 1973 performance of Lambert’s The Rio Grande. The piano soloist is Cristina Ortiz:

Almanac: W.H. Auden on evil

“Good can imagine Evil, but Evil cannot imagine Good.”

W.H. Auden, A Certain World