“Artists are artists because they have an extra sensitivity–a skin less, perhaps, than other people.” So said Benjamin Britten, and I remembered his words when I learned that Philip Seymour Hoffman had died of a heroin overdose.

Actors are peculiarly sensitive creatures. Some of them are so desperate for approval and unsure of their own identities that they will go to great and dangerous lengths merely to get through the day, much less a performance. I know nothing about Hoffman’s private life, but anyone who dies as he did must have felt the pain of the damned. That he still managed to leave behind so much eloquent evidence of his extraordinary talent now looks in retrospect like something of a miracle.

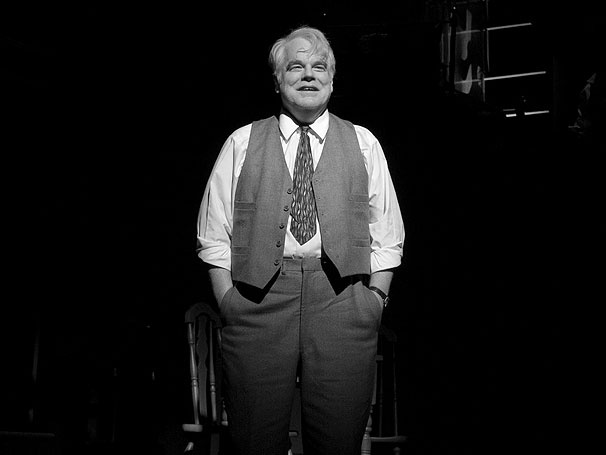

Hoffman was as good on stage as on screen, and I had the honor to review his performance as Willy Loman in Mike Nichols’ 2012 revival of Death of a Salesman. This is what I wrote about it:

Hoffman was as good on stage as on screen, and I had the honor to review his performance as Willy Loman in Mike Nichols’ 2012 revival of Death of a Salesman. This is what I wrote about it:

Philip Seymour Hoffman, the star of Mike Nichols’ revival of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” is following in the well-remembered footsteps of Lee J. Cobb, George C. Scott, Dustin Hoffman and Brian Dennehy, and it’s a tribute to his talent that you won’t feel inclined to compare him to any of his predecessors. When he first comes trudging onto the stage, carrying his weatherbeaten sample cases as though each one contains half the weight of the world, you feel at once that you’re seeing not a performance but a person, stooped and stunned by the burden of failure. No sooner does he sigh “Oh, boy, oh, boy” than you forget all about the actor and follow Willy down the stony road to the open grave that awaits him at play’s end.

I’m glad I was there that night. I hope he was proud of what he did.

* * *

A scene from Capote, written by Dan Futterman, directed by Bennett Miller, and starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, and Chris Cooper: