An extremely rare video of Claude Thornhill performing “There’s a Small Hotel” on WGN’s The Big Bands in 1965:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An extremely rare video of Claude Thornhill performing “There’s a Small Hotel” on WGN’s The Big Bands in 1965:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

“In some deep place I always believed that what anyone else was feeling or doing, wether it be an act of heroism or cowardice or compassion or greed or villainy or anything in between, whatever the characters were going through emotionally was possible for me. I sensed that the entire range of emotions possessed by one human being was universal and available to everyone. Each of us had our own emphases and proclivities, but I intuitively believed that all of us were possessed of the entire spectrum of human feelings, and nothing that I’ve seen or felt since has convinced me otherwise.”

Alan Arkin, An Improvised Life

I review three New York shows in today’s Wall Street Journal, Frank Langella’s King Lear, the Broadway revival of Sophie Treadwell’s Machinal, and Beautiful: The Carole King Musical. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

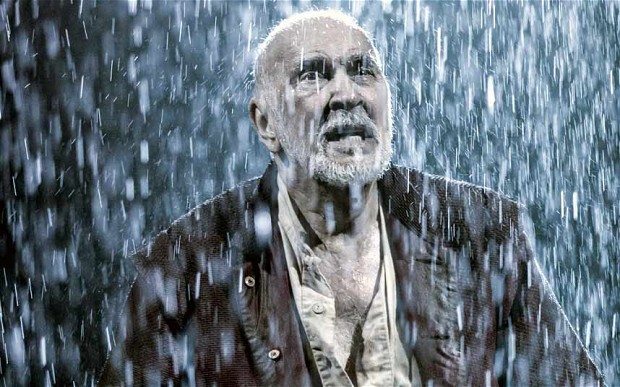

Frank Langella is a stage actor of immense charisma and potency, and King Lear is the role to which all such men aspire as they grow older and confront the prospect of their coming demise. So it makes perfect sense that Mr. Langella, who turned 76 earlier this month, should have chosen to take it on. But even though he once played the part of William Shakespeare in William Gibson’s “A Cry of Players,” Mr. Langella has done surprisingly little Shakespearean acting, nor is he especially well known as a classical actor. Indeed, he confesses to never even having read “King Lear” (which is quite a thing for a distinguished stage actor to admit) before agreeing to star in Angus Jackson’s production, which has transferred to BAM Harvey after a run at England’s Chichester Festival. So what can be reasonably expected out of him, and what does he deliver?

Throughout most of the first half of the evening, Mr. Langella gives us an old-fashioned star-turn Lear: big, blustering, monochromatic and deaf to the tolling of Shakespeare’s verse. Imposing, yes–he has the rafter-raising voice to play a king–but not compelling, even though the production is structured to show him off. (He’s actually introduced with a clap-for-the-star fanfare.) But then, like Ian McKellen and Christopher Plummer before him, he finds his footing when he renounces his throne and sees for the first time the world as it really is, cold and hostile to the vanity of human wishes. “Is man no more than this?” he cries at the piteous spectacle of the half-naked Edgar (Sebastian Armesto) trembling in the storm, and in an instant he is invaded and conquered by self-doubt. Thereafter Mr. Langella is a great Lear, gaunt, hushed and human….

Throughout most of the first half of the evening, Mr. Langella gives us an old-fashioned star-turn Lear: big, blustering, monochromatic and deaf to the tolling of Shakespeare’s verse. Imposing, yes–he has the rafter-raising voice to play a king–but not compelling, even though the production is structured to show him off. (He’s actually introduced with a clap-for-the-star fanfare.) But then, like Ian McKellen and Christopher Plummer before him, he finds his footing when he renounces his throne and sees for the first time the world as it really is, cold and hostile to the vanity of human wishes. “Is man no more than this?” he cries at the piteous spectacle of the half-naked Edgar (Sebastian Armesto) trembling in the storm, and in an instant he is invaded and conquered by self-doubt. Thereafter Mr. Langella is a great Lear, gaunt, hushed and human….

Inspired, as was James M. Cain’s “Double Indemnity,” by a once-celebrated, now-forgotten murder trial of the Roaring ’20s, “Machinal” tells the story of a sensitive but inarticulate stenographer (Rebecca Hall) who marries her boss (Michael Cumpsty), then murders him after taking a lover (Morgan Spector) and learning that her spirit has been crushed by the soullessness of life under industrial capitalism. That is, to put it mildly, an oft-told tale, and the quaint expressionist idiom in which it is told here is far more familiar today than it was in 1928. Indeed, the staccato I-am-a-dehumanized-robot clichés spouted by Ms. Treadwell’s characters suggest at times a “Saturday Night Live” parody of an Aaron Sorkin sitcom: “She doesn’t belong in an office.” “Who does?” “I do!” “You said it!” “Hot dog!”

What brings this “Machinal” to life is the acting. Ms. Hall, a British stage actor who is best known to American audiences for her glowing performance in Ben Affleck’s “The Town,” is so unselfconsciously winning that you can’t help but warm to her plight….

Jessie Mueller is surely destined for musical-comedy stardom. Not only is she the best singer to hit Broadway since Kelli O’Hara, but she’s also an accomplished actor, and “Beautiful: The Carole King Musical,” in which she plays the title role, allows her to display both sides of her exceptional talent. The problem is that what she does in “Beautiful” is a cross between a superlative piece of character acting and an impersonation–a creative and affecting one, to be sure, but an impersonation all the same. Close your eyes and you’ll think you’re hearing Ms. King’s own plaintive, nasal singing voice. Open them and you’ll see a shy Brooklyn housewife who becomes a successful singer-songwriter almost in spite of herself, which is by all accounts what Ms. King was in real life. It’s a totally persuasive performance that serves the show unselfishly, but most people who see it will likely come away thinking of Ms. King, not Ms. Mueller, which isn’t how stars are born.

Jessie Mueller is surely destined for musical-comedy stardom. Not only is she the best singer to hit Broadway since Kelli O’Hara, but she’s also an accomplished actor, and “Beautiful: The Carole King Musical,” in which she plays the title role, allows her to display both sides of her exceptional talent. The problem is that what she does in “Beautiful” is a cross between a superlative piece of character acting and an impersonation–a creative and affecting one, to be sure, but an impersonation all the same. Close your eyes and you’ll think you’re hearing Ms. King’s own plaintive, nasal singing voice. Open them and you’ll see a shy Brooklyn housewife who becomes a successful singer-songwriter almost in spite of herself, which is by all accounts what Ms. King was in real life. It’s a totally persuasive performance that serves the show unselfishly, but most people who see it will likely come away thinking of Ms. King, not Ms. Mueller, which isn’t how stars are born.

As for “Beautiful” itself, it’s a staged biopic whose sitcommish book (written by Douglas McGrath) is the merest of pretexts for the singing of two dozen pop hits from the ’60s and early ’70s. Most of them were penned by Ms. King and Gerry Goffin, her lyricist when they were married to one another, and most are amiable Top-40 confections like “The Locomotion” and “One Fine Day.” Ms. King, however, was a truly gifted tunesmith, and some of the numbers in the show, “It’s Too Late,” “Up on the Roof” and “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” in particular, are excellent by any possible standard….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I hold forth on the problems faced by the drama critic who is called upon to review stage adaptations of familiar source material. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

After the film version of Tracy Letts’ “August: Osage County” came out last month, it soon emerged that most of the critics who reviewed it hadn’t seen the play. (Not so my esteemed colleague Joe Morgenstern, who saw it on Broadway and made good use of the experience in writing his piece.) The result was a Twitter spat in which exasperated theater people argued that it wasn’t responsible to review a screen adaptation of so important a play without having seen the original version.

After the film version of Tracy Letts’ “August: Osage County” came out last month, it soon emerged that most of the critics who reviewed it hadn’t seen the play. (Not so my esteemed colleague Joe Morgenstern, who saw it on Broadway and made good use of the experience in writing his piece.) The result was a Twitter spat in which exasperated theater people argued that it wasn’t responsible to review a screen adaptation of so important a play without having seen the original version.

I haven’t seen the film version yet, though I will as soon as I can. For now, though, I don’t have a horse in that particular race. Instead, I’d like to approach the question from the opposite direction. What about drama critics who find themselves called on, as is often the case, to review a show adapted from a pre-existing piece of source material–a novel or, in the case of musicals, a movie–or based on a true story? How much, if anything, must they know to do the job right? It’s tempting to say that it depends on how serious the show is. I’m not at all sure that my review of “Legally Blonde: The Musical” was any better because I’d seen the movie. But even in the case of a commodity musical, it’s not quite as simple as that….

For me, Peter Shaffer’s “Amadeus,” a play about the rivalry between Antonio Salieri and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart that was first staged in 1979 and later turned into a popular film by Milos Forman, is the ideal test case. You don’t have to see the play to appreciate the movie, which was skillfully adapted by Mr. Shaffer himself. Nor is it necessary to know anything about Mozart or Salieri to enjoy either version of “Amadeus.” The script tells you all you need to know (though quite a bit of the “information” in “Amadeus” is untrue, which definitely makes the reviewer’s job more interesting). But a drama critic who reviews a revival of “Amadeus” must know something about Mozart’s life and work in order to properly appreciate the play, which is a gripping parable of the terrible mystery of human inequality as seen in the complex relationship between Mozart and Salieri. What’s more, he really ought to have seen the film, too, since nearly everybody knows it far better than the play…

For me, Peter Shaffer’s “Amadeus,” a play about the rivalry between Antonio Salieri and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart that was first staged in 1979 and later turned into a popular film by Milos Forman, is the ideal test case. You don’t have to see the play to appreciate the movie, which was skillfully adapted by Mr. Shaffer himself. Nor is it necessary to know anything about Mozart or Salieri to enjoy either version of “Amadeus.” The script tells you all you need to know (though quite a bit of the “information” in “Amadeus” is untrue, which definitely makes the reviewer’s job more interesting). But a drama critic who reviews a revival of “Amadeus” must know something about Mozart’s life and work in order to properly appreciate the play, which is a gripping parable of the terrible mystery of human inequality as seen in the complex relationship between Mozart and Salieri. What’s more, he really ought to have seen the film, too, since nearly everybody knows it far better than the play…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Paul Scofield plays Salieri in a scene from the original stage production of Amadeus:

F. Murray Abraham plays Salieri in the corresponding scene from the film version of Amadeus:

“In general, when reading a scholarly critic, one profits more from his quotations than from his comments.”

W.H. Auden, “Reading” (in The Dyer’s Hand)

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• No Man’s Land/Waiting for Godot (drama, PG-13, playing in rotating repertory, extended through Mar. 30, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

• Twelfth Night (Shakespeare, G/PG-13, closes Feb. 16, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Commons of Pensacola (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 9, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Hamlet/Saint Joan (drama, G/PG-13, remounting of off-Broadway production, playing in rotating repertory, extended through Mar. 9, original production reviewed here)

• The Night Alive (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 2, reviewed here)

IN GLENCOE, ILL.:

• Port Authority (drama, PG-13, closes Mar. 2, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN FORT MYERS, FLA.:

• Arsenic and Old Lace (drama, G, closes Jan. 29, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK OFF BROADWAY:

• Juno and the Paycock (drama, G/PG-13, far too dark for children, closes Jan. 26, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO, ILL.:

• The Merry Wives of Windsor (Shakespeare, PG-13, reviewed here)

“All poets adore explosions, thunderstorms, tornadoes, conflagrations, ruins, scenes of spectacular carnage. The poetic imagination is not at all a desirable quality in a statesman.”

W.H. Auden, “The Poet & The City” (in The Dyer’s Hand)

From D.A. Pennebaker’s 1970 documentary Company: Original Cast Album, Dean Jones sings Stephen Sondheim’s “Being Alive” at the recording sessions for the original-cast album of Company:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

An ArtsJournal Blog