“I suggest that the voice you hear today in all branches of literature is not the individual voice but the collective voice. And this especially from any writer under forty. In other words, the writer has become the spokesman not for himself but for a group, an organisation, a class or a sect. The danger is that some don’t know they are doing it, and those who do know often consider, and are led to consider it a virtue. ‘This young man speaks for his generation.’ ‘This young woman is the rallying point for all young women with big feet.’ You know the sort of thing.”

John Whiting, At Ease in a Bright Red Tie: Writings on Theatre (courtesy of George Hunka)

Archives for January 2014

TT: Snapshot

“Scotch Rhapsody,” from William Walton’s Façade. The poem is by Edith Sitwell and the speakers are Glenn Gould and Patricia Rideout:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“I suggest that the voice you hear today in all branches of literature is not the individual voice but the collective voice. And this especially from any writer under forty. In other words, the writer has become the spokesman not for himself but for a group, an organisation, a class or a sect. The danger is that some don’t know they are doing it, and those who do know often consider, and are led to consider it a virtue. ‘This young man speaks for his generation.’ ‘This young woman is the rallying point for all young women with big feet.’ You know the sort of thing.”

John Whiting, At Ease in a Bright Red Tie: Writings on Theatre (courtesy of George Hunka)

TT: Scene of the crime

Today I’m flying up to New York from Florida to rehearse my first play. Last night I slept in the room where, four years ago this month, I wrote it.

I remember that week as though it had been last week. John Schreiber, who now runs the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, had written to me from out of the blue on Christmas Eve, telling me that he’d just read Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong and wondered whether there might be a play in it:

Reading your book, I saw (in my mind) a one-person show of Louis’ life told by Louis with the specificity, sensitivity, wisdom, humor and sense of history and moment that shines through in your storytelling. Pops was a great man and a great artist whose life intimately intersected with (and sometimes led) American culture for seventy years.

Is there a theatrical here? Lord knows. If you’re game, I’d love to discuss the possibility with you.

Until then I’d given no thought whatsoever to writing a play, about Armstrong or anyone else, but John had been a producer in a previous life, and it struck me that I ought to take his suggestion seriously.

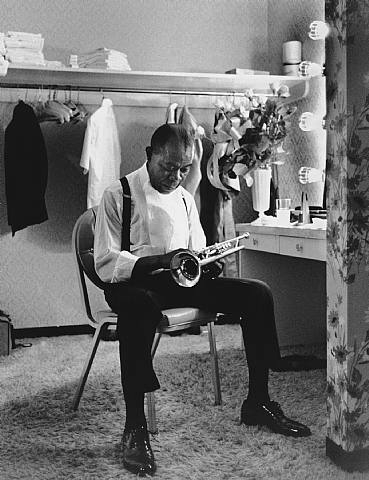

A couple of weeks later, Mrs. T and I went down to Winter Park, Florida, so that I could spend a month as scholar-in-residence at Rollins College’s Winter Park Institute. As a result, I had–for once–some free time on my hands. I found myself thinking about the next-to-last illustration in Pops, Eddie Adams’ famous photograph of Armstrong sitting backstage in a Las Vegas dressing room a few months before his death in 1971, looking old and weary.

A couple of weeks later, Mrs. T and I went down to Winter Park, Florida, so that I could spend a month as scholar-in-residence at Rollins College’s Winter Park Institute. As a result, I had–for once–some free time on my hands. I found myself thinking about the next-to-last illustration in Pops, Eddie Adams’ famous photograph of Armstrong sitting backstage in a Las Vegas dressing room a few months before his death in 1971, looking old and weary.

All at once the idea for a one-man play about Armstrong’s last gig popped into my head. It wasn’t quite fully formed, but it was close enough to allow me to get started. I sat down and went to work. Four days later I typed the last sentence of the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf and emerged from a near-hypnotic frenzy of creativity. It had poured out of me so fast that I felt as though I’d been invaded by a demon, and was forced to exorcise myself by writing until I dropped.

On January 25 I publicly acknowledged for the first time what I’d been up to:

I’ve been working on a new opera libretto and–brace yourself–a play. Yes, the play is a great big honking maybe, but we’ll see what, if anything, comes of it.

Now we know. What followed was a long, improbable journey that has led me at last to the stage door of New York’s Westside Theatre, where Satchmo will open on March 4. But it started right here, in the upstairs office-bedroom of a condo owned by Rollins College, and returning there on Saturday afternoon felt more than a little bit like coming home.

Mrs. T and I have spent a total of three stretches in this comfortable apartment, long enough to be able to find our way around in the dark. It’s a five-minute walk from our front door to the center of campus. The surrounding neighborhood is leafy and quiet, but close enough to the railroad tracks that you can easily hear train whistles blowing in the middle of the night.

Mrs. T and I have spent a total of three stretches in this comfortable apartment, long enough to be able to find our way around in the dark. It’s a five-minute walk from our front door to the center of campus. The surrounding neighborhood is leafy and quiet, but close enough to the railroad tracks that you can easily hear train whistles blowing in the middle of the night.

A good place to write, in other words, and I’ve taken full advantage of it over the years. Among other things, I’ve knocked out a couple of dozen Wall Street Journal pieces in that office, as well as the first chapters of Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. This year I’m working on a lecture, a book proposal, and another play. But no matter how many times Mrs. T and I return here in the future, I doubt I’ll ever again have a week quite like the one that turned me, for better or worse, into a playwright.

TT: Lookback

From 2004:

Ivy Compton-Burnett, the English novelist, told a friend late in life that she could no longer read Jane Austen with pleasure, not because her admiration for Austen had lessened but because she’d read her novels so many times that she had them virtually by heart, and hence could no longer be surprised by them. When I read that, I wondered: is it really possible to exhaust a masterpiece? Much less an entire art form? I can’t imagine being unable to hear anything new in Falstaff or the Mozart G Minor Symphony, though I suppose it could happen. And as for a person who came to feel that music or painting or poetry had nothing more to say to him, he’d be in dire straits indeed…

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“A work of art is the statement of one man. It is one of the noblest, because it is one of the most selfless activities of human existence. It has nothing to do with an audience or a wish to please. It does not necessarily entertain, instruct or enlighten. It can do any one or all of these things, but that it should is not the artist’s concern. That is the work of art in its perfect state. The thing is there: an audience taking from it what it can. It is not the artist’s job to simplify the means of communication.”

John Whiting, At Ease in a Bright Red Tie: Writings on Theatre (courtesy of George Hunka)

TT: Lookback

From 2004:

Ivy Compton-Burnett, the English novelist, told a friend late in life that she could no longer read Jane Austen with pleasure, not because her admiration for Austen had lessened but because she’d read her novels so many times that she had them virtually by heart, and hence could no longer be surprised by them. When I read that, I wondered: is it really possible to exhaust a masterpiece? Much less an entire art form? I can’t imagine being unable to hear anything new in Falstaff or the Mozart G Minor Symphony, though I suppose it could happen. And as for a person who came to feel that music or painting or poetry had nothing more to say to him, he’d be in dire straits indeed…

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“A work of art is the statement of one man. It is one of the noblest, because it is one of the most selfless activities of human existence. It has nothing to do with an audience or a wish to please. It does not necessarily entertain, instruct or enlighten. It can do any one or all of these things, but that it should is not the artist’s concern. That is the work of art in its perfect state. The thing is there: an audience taking from it what it can. It is not the artist’s job to simplify the means of communication.”

John Whiting, At Ease in a Bright Red Tie: Writings on Theatre (courtesy of George Hunka)