“Behind that brilliantly lit two hours onstage, life on the road for us is probably not much different from that of a salesman for electrical wire.”

Arnold Steinhardt, Indivisible by Four: A String Quartet in Pursuit of Harmony

Archives for 2013

TT: What I’m up to this week

I’m off to Chicago this morning, there to break bread with Our Girl and see three shows, Remy Bumppo’s revival of J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, Writers Theatre’s revival of Conor McPherson’s Port Authority, and Chicago Shakespeare’s updated Merry Wives of Windsor.

In the nonce, I’d like to tell you about my two latest undertakings:

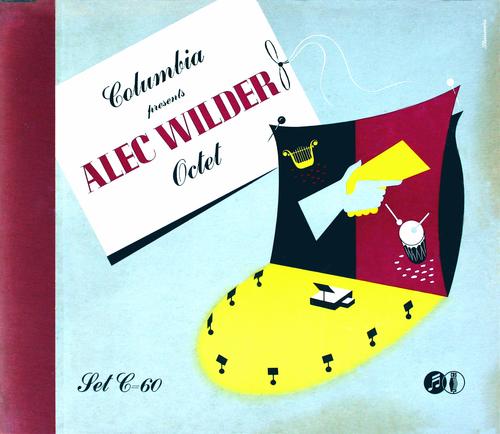

• Hep Records, a Scottish label that specializes in reissues commercial recordings and airchecks of performances by great jazz and pop musicians of the Thirties and Forties, has just released a two-disc set called Music for Lost Souls and Wounded Birds that is devoted in large part to the complete recordings of the Alec Wilder Octet. Alastair Robertson, the producer, asked me to write the liner notes:

• Hep Records, a Scottish label that specializes in reissues commercial recordings and airchecks of performances by great jazz and pop musicians of the Thirties and Forties, has just released a two-disc set called Music for Lost Souls and Wounded Birds that is devoted in large part to the complete recordings of the Alec Wilder Octet. Alastair Robertson, the producer, asked me to write the liner notes:

Alec Wilder spent his life looking for cracks to fall through. Though he wrote two songs, “I’ll Be Around” and “While We’re Young,” that became standards, most of his “popular” music was too delicate and introspective to please a mass audience. He also composed works for several of America’s finest instrumentalists, but these “classical” pieces were too strongly colored by jazz and popular music to win critical acceptance. Today he is mainly remembered for his book American Popular Song: The Great Innovators, 1900-1950–which has nothing to say about his own songs. All this suggests a man more than half in love with failure, and Wilder’s self-destructive behavior was no secret to those who knew him. Especially when drunk, he liked nothing better than to burn bridges, and had he been less charming when sober, he would surely have lost every friend he ever made.

Outside of his songs, Wilder’s most enduring achievement is–or should have been–the music of the Alec Wilder Octet, whose thirty 78 sides, recorded between 1938 and 1947, constituted one of the earliest sustained attempts to fuse jazz with classical music. But while the octet’s recordings attracted attention in the Thirties and Forties, they are now poorly remembered, in part because they were never reissued in their entirety prior to the release of this album….

The ensemble that recorded the octets, which seems never to have performed in public, consisted of a crack group of studio musicians led by Mitch Miller. The four sides cut at the first session sold well enough for Brunswick (and, later, Columbia) to bring the group back to the studio for five more sessions. Their fey titles, hauntingly nostalgic tunes, off-center harmonies, and piquant scoring delighted musicians and other sharp-eared listeners….

Music for Lost Souls and Wounded Birds will not be available in this country until next year, but you can order it directly from Hep. To do so, or to read more about the album, go here.

• Project Shaw, which presents concert-style semi-staged readings of the plays of George Bernard Shaw each month, is putting on The Devil’s Disciple next Monday night. David Staller, who probably knows more about Shaw than anybody in America, is the director. Project Shaw’s performances are never reviewed, but they’re quite extraordinarily good, so much so that I agreed to introduce Pygmalion last November. (Here’s what I said.)

I had so much fun that I accepted David’s invitation to serve as the narrator of The Devil’s Disciple. This will be the first time in thirty-five years that I’ve appeared on stage in a theatrical performance. Please come and cheer me on–or do the other thing, if you feel so inclined!

The show is at Symphony Space, 95th and Broadway, and starts at seven p.m. To order tickets or for more information, go here.

* * *

“Her Old Man Was Suspicious,” recorded in 1941 by the Alec Wilder Octet:

TT: Just because

Booker T. and the MGs play “Red Beans and Rice” in Oslo in 1967:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Striving for the unreachable is really quite splendid.”

Rudolf Serkin (quoted in Stephen Lehmann and Marion Faber, Rudolf Serkin: A Life)

TT: The ties that blind

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report enthusiastically on two A.R. Gurney productions, the premiere in New York of Family Furniture and a Boston revival of The Cocktail Party. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

To be prolific is to be uneven. A.R. Gurney has written a lot of plays in the past decade, some of them good, others less so, but none quite so fine as the ones that won him a permanent place in the history of American theater. So I rejoice to report that his newest play, “Family Furniture,” is exactly that fine–and that its distinguished author is 83 years old. Not since 1995 and “Sylvia” has Mr. Gurney given us so penetrating and disciplined a play.

“Family Furniture” is a exceptionally well-cast, somewhat longish one-act play (long enough that I think it might possibly profit from being performed with an intermission) that starts out at a gallop and moves unswervingly to its stark, sad conclusion. Four of the five characters are members of a family of WASPs from upstate New York that is sitting on a secret, which is that the mother (Carolyn McCormick) appears to be sleeping with one of their neighbors behind the back of her stuffy, seemingly oblivious husband (Peter Scolari). The children (Andrew Keenan-Bolger and Ismenia Mendes) are appalled, while the son’s Jewish girlfriend (Molly Nordin) thinks that they ought to force the affair out into the open.

Those are the cards in Mr. Gurney’s hand–most of them, anyway–and he plays them with enviable skill, triggering a string of surprises in the second half that up the ante considerably. But “Family Furniture” is not a family melodrama: It’s a Terence Rattigan-like tale of strong but largely unspoken emotions, and the penny-plain simplicity of Thomas Kail’s production (which is played on a near-bare stage in a 74-seat Off-Broadway house) brings us close enough to the characters to feel each twinge of their collective pain….

In a happy coincidence, the Huntington Theatre Company is mounting a superior revival of “The Cocktail Hour,” the 1988 play in which Mr. Gurney cemented the reputation for excellence that he had won in 1982 with “The Dining Room.” It’s a quasi-autobiographical comedy with a Pirandello-like twist in which an angry young playwright (James Waterston) comes home to Buffalo to inform his horrified family (Maureen Anderman, Pamela J. Gray and Richard Poe) that he has just written a play about them called (naturally) “The Cocktail Hour.” The plot is not altogether unlike that of “Family Furniture,” but it’s played for laughs and ends in what the aggressively genial father, played to perfection by Mr. Poe, calls “an appreciative mood.”…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Is that all there is?

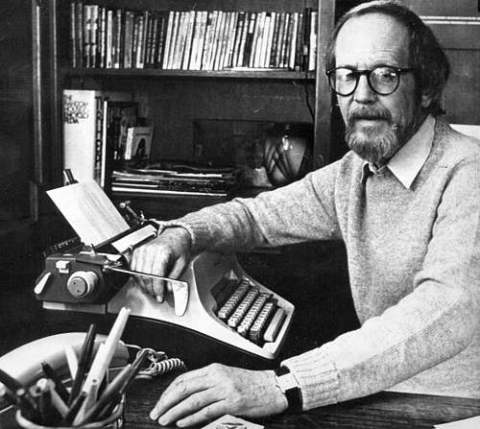

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I reflect on the novels of Elmore Leonard and the limitations of pop culture. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When Elmore Leonard died in August, the papers were full of obituaries that described him as “a novelist who made crime an art.” So, at any rate, declared a headline writer for the New York Times. A year earlier, the National Book Foundation had presented Mr. Leonard with its annual medal for “distinguished contribution to American letters,” calling him a “great American author,” and the Library of America announced that it would be bringing out a three-volume edition of his work in 2014. I didn’t want to rain on his cortege, so I didn’t say what I thought, which was that he was one of the most overpraised writers of our time. A very good one, mind you–I’m a passionate fan of Mr. Leonard’s brisk, funny crime novels–but overpraised all the same.

What’s wrong with his books? For one thing, they’re repetitious to a fault. I can’t count the number of Mr. Leonard’s novels that revolve around a divorced man of a certain age who falls hard for a wised-up younger woman. On the other hand, a cheeseburger is a cheeseburger. No matter how many you’ve eaten, you can usually make room for another one if it’s good, and Mr. Leonard wrote a lot of good books, “LaBrava,” “Maximum Bob” and “Tishomingo Blues” in particular.

What’s wrong with his books? For one thing, they’re repetitious to a fault. I can’t count the number of Mr. Leonard’s novels that revolve around a divorced man of a certain age who falls hard for a wised-up younger woman. On the other hand, a cheeseburger is a cheeseburger. No matter how many you’ve eaten, you can usually make room for another one if it’s good, and Mr. Leonard wrote a lot of good books, “LaBrava,” “Maximum Bob” and “Tishomingo Blues” in particular.

So why grump about his obituaries? Because they exemplify a trend that has gotten out of hand. It used to be that we didn’t take popular culture seriously, but now we don’t take anything else seriously….

The problem is not that pop culture doesn’t deserve to be taken seriously. It’s that a culture totally dominated by popular art is by definition limited. Let’s go back to Elmore Leonard’s novels for a moment. Sure, they’re superbly crafted, but they’re all pure melodramas whose subject is crime, with a little romance thrown in for seasoning. So, almost without exception, are the TV series that have come of late to be widely regarded as the best that America’s storytellers have to offer. From “Hill Street Blues” to “The Sopranos” to “Breaking Bad,” these series are all thrillers of one kind or another. To be sure, they use the time-honored conventions of genre fiction to explore many other aspects of American life–but in the end, somebody always gets shot, just as a pop song, no matter how good it may be, is almost always three minutes long….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Even a Saint finds it hard, now and again, to be quite sure why he is doing a thing. It is unlikely that such an one will be completely deluded as to his motive, let alone do something with a consciously wrong motive; but the anguish of life is, that a good man finds he is doing things with mixed motives.”

C.C. Martindale, The Vocation of Aloysius Gonzaga

NORA EPHRON’S SECRET HEART

“When Nora Ephron died in 2012, many who wrote to mourn her passing gave the impression of feeling they had lost someone close to them–regardless of whether or not they had known her personally. Nowhere was that feeling more common than in New York. Though she was the child of a pair of Hollywood screenwriters, grew up in Beverly Hills, and later directed eight of her own scripts, Ephron moved back to Manhattan after graduating from college and stayed there for most of the rest of her life. For New Yorkers of her generation–she was born in 1941–her essays and films, like those of Woody Allen, were a touchstone of identity and urban-nationalist pride…”