“Let all Men know thee, but no man know thee thoroughly: Men freely ford that see the shallows.”

Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard’s Almanack

Archives for 2013

WHEN THE MUSIC STOPS: A TALE OF TWO CITIES

“Is it possible to fix things after a debilitating, trust-destroying work stoppage? The good news is that the Detroit Symphony, which went out on strike for six months in 2010-11, seems to have found a way to do so…”

TT: Lookback

From 2005:

From 2005:

I left my toothbrush behind in my hotel room in Montgomery, and the spare in my Manhattan medicine cabinet proved to be an unpleasant shade of purple. Alas, not only is my bathroom decorated in sunny yellow and cornflower blue, but a Bonnard color lithograph hangs next to the door. Having gone to some trouble last year to track down a suitably blue toothbrush, I went back to the corner drugstore to look for something a bit more compatible with my décor. To my horror, all the brushes they now sell turn out to be vulgar, fat-handled implements that not only don’t match my towels but won’t even fit into my toothbrush holder….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Ambition has its disappointments to sour us, but never the good fortune to satisfy us.”

Benjamin Franklin, “On True Happiness”

TT: Return of the flâneur

Longtime readers of this blog may recall that I used to get out a lot more often. The truth is that I spend roughly the same amount of time in places other than my apartment, but I spend a larger chunk of it at the theater, both in New York and on the road. As a result, I have less time to see other things. Mrs. T, whose interests are as wide-ranging as my own, has been warning me of late not to get stuck in a rut, so I took her to the opera last month, and over the weekend we attended a nonstop string of performances that put me in mind of the days when I seemed never to be home after dark.

On Friday afternoon we drove from rural Connecticut to Red Bank, New Jersey, the home of Count Basie, Edmund Wilson, and Two River Theater Company, which has just mounted a revival of Present Laughter, my favorite Noël Coward play, whose star, Michael Cumpsty, is one of my favorite stage actors. We were there for professional reasons, of course–I’ll be reviewing the show in Friday’s Wall Street Journal–but we went with the reasonable expectation of having a good time.

On Friday afternoon we drove from rural Connecticut to Red Bank, New Jersey, the home of Count Basie, Edmund Wilson, and Two River Theater Company, which has just mounted a revival of Present Laughter, my favorite Noël Coward play, whose star, Michael Cumpsty, is one of my favorite stage actors. We were there for professional reasons, of course–I’ll be reviewing the show in Friday’s Wall Street Journal–but we went with the reasonable expectation of having a good time.

I’ll have plenty to say about the production on Friday, but I can tell you now that we had a frightful time getting to Red Bank. The sky fell on Friday, and what should have been a three-hour road trip took twice as long. We spent the whole of it clawing our way through heavy rain and heavier traffic, arriving at the theater at 7:45, far too late to have dinner before the show. Later that night we made the mistake of stopping at a Burger King on the Garden State Parkway. I’m pretty tolerant when it comes to fast food, but should you ever be unfortunate enough to find yourself at the Cheesequake service area, don’t eat anything.

It was still pouring when we reached upper Manhattan, where I unloaded the car, dropped Mrs. T at our front door, and drove straight to the nearest parking garage, which was full. I’ll draw a veil of discretion over the soggy half-hour that followed.

On Saturday we hauled ourselves out of bed and went to Penn Station to pick up my carry-on bag, which I’d left in Washington, D.C., six days earlier. That’s another story, so I’ll skip to the good part, which is that Amtrak found the bag and shipped it to New York gratis. What’s more, the contents, which included a brand-new GPS and two months’ worth of expense-account receipts, were intact. I do solemnly swear never to tweet about Amtrak’s wi-fi service again.

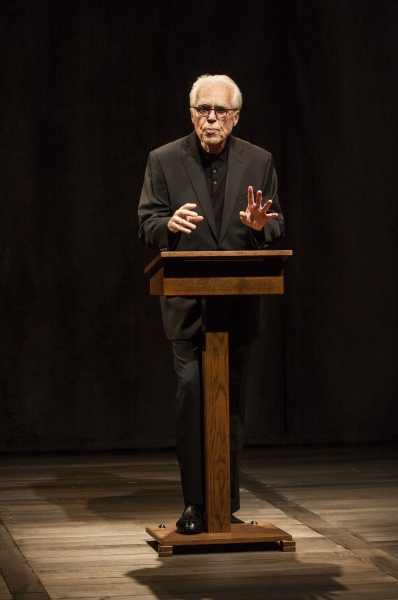

From there we took a cab to the Atlantic Theater Company, where we saw a preview of 3 Kinds of Exile, John Guare’s new play. It’s no secret that I admire Guare pretty much without reserve, and this production is all the more noteworthy given the fact that it also constitutes his professional acting debut. It would be an understatement to say that I now also admire his nerve!

From there we took a cab to the Atlantic Theater Company, where we saw a preview of 3 Kinds of Exile, John Guare’s new play. It’s no secret that I admire Guare pretty much without reserve, and this production is all the more noteworthy given the fact that it also constitutes his professional acting debut. It would be an understatement to say that I now also admire his nerve!

Once again, I’ll keep my opinions to myself–you can read them on Friday–but it’s worth noting how unusual it is for a major playwright who is not already known as an actor to assume a role in one of his own plays. Thornton Wilder did it more than once, appearing in Our Town as the stage manager several times in the Thirties and Forties, and he also played the part in a 1946 Theatre Guild on the Air radio broadcast in which he shared the microphone with Dorothy McGuire. (I’ve heard an air check of the performance, which is fascinating.) Since then, no other name springs readily to mind.

We got home in time for a much-needed nap, after which we headed back downtown. This time our destination was the Jazz Standard, where we ate barbecue and listened to Jim Hall, the best of all possible jazz guitarists. Not only is Hall the greatest living jazz soloist, but he’s eighty-two years old, so I decided that it was damned well about time for Mrs. T to hear him in person.

ArtistShare recently brought out a wonderful three-disc set of live recordings made in 1975 by Hall, Don Thompson, and Terry Clarke at the same Toronto gig that produced Jim Hall Live! The latter album, which didn’t make it to CD, amazingly enough, until 2003, is by common consent Hall’s greatest recording, a judgment in which I wholeheartedly concur. That doesn’t mean his playing has been on the decline since 1975, though. To the contrary, it’s grown increasingly subtle and daring. Yes, Hall looks frail–he walks with a cane–but you’d never guess his age from hearing him play.

ArtistShare recently brought out a wonderful three-disc set of live recordings made in 1975 by Hall, Don Thompson, and Terry Clarke at the same Toronto gig that produced Jim Hall Live! The latter album, which didn’t make it to CD, amazingly enough, until 2003, is by common consent Hall’s greatest recording, a judgment in which I wholeheartedly concur. That doesn’t mean his playing has been on the decline since 1975, though. To the contrary, it’s grown increasingly subtle and daring. Yes, Hall looks frail–he walks with a cane–but you’d never guess his age from hearing him play.

I interviewed Hall ten years ago for The Wall Street Journal. He said something to me back then that has stuck in my mind:

My playing used to be a little bit conservative, but I think I’ve gained courage. It’s not that I’m playing better. I certainly don’t have more chops. I guess it’s just lack of fear! I just basically don’t give a damn now. I feel I’m O.K. Miles Davis was a hero of mine in a lot of ways, and I always figured Miles was kind of like Picasso–he just sort of kept letting himself grow. That’s what I’m trying to do, let myself grow. Sort of like a painter, or a writer. I don’t want to live in the past.

He didn’t then. He doesn’t now.

Back to bed, then up again at noon to go to Lincoln Center. I recently resolved to introduce Mrs. T to the miracle that is George Balanchine, and on Sunday I delivered the goods by taking her to New York City Ballet for an all-Balanchine matinee.

The program was supposed to start with Concerto Barocco, which is set to Bach’s Two-Violin Concerto. It happens that Concerto Barocco also opened the program when I paid my own first visit to NYCB in the winter of 1987, an experience that changed my life. I wrote about it in All in the Dances, my brief life of Balanchine:

At five minutes past eight, the houselights went down and the curtain flew up, revealing eight young women dressed in simple white ballet skirts, standing in front of a blue backdrop. The scrappy little band in the pit slouched to attention, the conductor gave the downbeat, and the women started to move, now in time to Bach’s driving beat, now cutting against its grain. As the solo violinists made their separate entrances, two more women came running out from the wings and began to dance at center stage. Their steps were crisp, precise, almost jazzy….They made no obviously theatrical gestures, exchanged no significant glances, yet I felt sure they were telling some kind of story. Was I missing the point? All at once I understood: the music was the story. The dancers were mirroring its complex events, not in a singsongy, naively imitative way but with sophistication and grace. This was no dumb show, no mere pantomime, but sound made visible, written in the air like fireworks glittering in the night sky. When it was over, eighteen breathless minutes later, the audience broke into friendly but routine applause, seemingly unaware that it had witnessed a miracle. Rooted in my seat, eyes wide with astonishment, I asked myself, Why hasn’t anybody ever told me about this?

Alas, Sunday’s program was changed at the last minute, but in a way that didn’t trouble me in the least: Barocco was replaced by Serenade, Balanchine’s first American ballet, a setting of Tchaikovsky’s C Major String Serenade that is widely and rightly thought to be an ideal introduction to his work. Next came Stravinsky Violin Concerto, one of his late masterpieces, followed by Stars and Stripes, a “dessert” ballet set to the fetchingly vigorous music of none other than John Philip Sousa.

Alas, Sunday’s program was changed at the last minute, but in a way that didn’t trouble me in the least: Barocco was replaced by Serenade, Balanchine’s first American ballet, a setting of Tchaikovsky’s C Major String Serenade that is widely and rightly thought to be an ideal introduction to his work. Next came Stravinsky Violin Concerto, one of his late masterpieces, followed by Stars and Stripes, a “dessert” ballet set to the fetchingly vigorous music of none other than John Philip Sousa.

The three works made for a well-balanced bill, and it had the desired effect on Mrs. T. “You can take me to the ballet any time,” she said as we left the theater to go to a rowdy engagement party (yes, there’s more!) for two close friends who decided to tie the knot.

That, in a jumbo nutshell, is what we did all weekend. Even for me, it was more than usually hectic, and I don’t plan to undertake anything like it again, at least not in the immediate future. But oh, how much fun it was to gallop once more from show to show, sharing with my beloved Mrs. T the beauty that is so indispensable to my existence! While I can’t say that our joint marathon made me feel younger–I don’t know when I’ve been so tired as I was on Saturday night–it definitely made me feel happier.

P.S. No, we didn’t watch the Tonys after we got home on Sunday, but I’m awfully glad that Tracy Letts won one.

* * *

Pacific Northwest Ballet dances an excerpt from the finale of George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco:

TT: Just because

Jim Hall undergoes a mock audition for Mort Lindsey’s studio band on The Merv Griffin Show in 1965:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“There is no error so monstrous that it fails to find defenders among the ablest men.”

Lord Acton, letter to Mary Gladstone (Apr. 24, 1881)

TT: The man that got away

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review two musicals, one in New York and one in Arlington, Virginia. The first, a stage version of Far From Heaven, is flawed but very interesting. The second, a revival of Company, is first-rate. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Is it possible to make a good musical out of a bad movie? In the case of “Far From Heaven,” many people may wonder why I’m even asking, since Todd Haynes’ 2002 cinematic homage to the humid domestic tragedies of Douglas Sirk is much admired by film buffs. But I find it to be at least as preposterous as Sirk’s sudsy tearjerkers, and I came to Playwrights Horizons expecting to file a scorched-earth pan. Nothing doing. “Far From Heaven” is far from perfect, but it’s vastly superior to the film on which it’s based, and Kelli O’Hara’s performance as Cathy Whitaker, an apple-cheeked Connecticut housewife whose all-American husband (Steven Pasquale) dumps her for a male lover, is so persuasive that you’ll gladly overlook most of the residual problems….

What makes the stage version of “Far From Heaven” work is the score. Instead of ersatz Technicolor movie music, Scott Frankel has given us clean, crisp harmonies that drain away the melodrama, making it possible to take the Whitakers’ plight at face value. Michael Korie, Mr. Frankel’s collaborator, studiously avoids archness, and though his lyrics are never memorable in their own right, they articulate the plot efficiently.

What makes the stage version of “Far From Heaven” work is the score. Instead of ersatz Technicolor movie music, Scott Frankel has given us clean, crisp harmonies that drain away the melodrama, making it possible to take the Whitakers’ plight at face value. Michael Korie, Mr. Frankel’s collaborator, studiously avoids archness, and though his lyrics are never memorable in their own right, they articulate the plot efficiently.

Ms. O’Hara is the musical-theater counterpart of Donna Reed, and those who remember Ms. Reed from such wartime films as “From Here to Eternity” and “They Were Expendable” will recognize that as a high compliment….

To call a theatrical production “exemplary” may sound like suspiciously faint praise, but I don’t mean it that way in the case of Signature Theatre’s staging of “Company,” the 1970 musical in which Stephen Sondheim and George Furth cast a cold eye on marital bliss. This is the kind of show in which all the pieces fit together so tightly that you’ll be caught up in the action mere seconds after the conductor throws the downbeat.

Where John Doyle’s 2006 small-scale Broadway revival of “Company” was formidably, almost excessively imaginative, Eric Schaeffer, who knows as much about Mr. Sondheim’s more-bitter-than-sweet musicals as any director in America, has chosen to stick to the center of the road, letting the show make its own dramatic points. The only hint of a high concept is Daniel Conway’s glass-and-metal set, which looks as though it might be meant to suggest the décor of a 70’s TV variety show–a smart touch, since Mr. Furth’s book consists of a string of hard-edged comic sketches….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The trailer for Company: