An excerpt from a 1980 Gloucester Cathedral performance of Britten’s War Requiem. The soloists are Galina Vishnevskaya and Peter Pears:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Archives for 2013

TT: Almanac

“The charm of the past is that it is past, but women never know when the curtain has fallen. They always want a sixth act.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

TT: Lookback

From 2004:

That said, one thing about Rope struck me quite forcibly. In fact, it astonished me. About ten minutes or so into the first reel, Hitchcock’s wandering camera came to rest in front of a painting hanging in the dining room of the elaborate breakaway set on which Rope was filmed. As Dall and Farley Granger chatted away, I said to myself, “By God, that’s a Milton Avery.” To be exact, it appears to be a portrait of March Avery, the artist’s daughter, painted some time in the mid-to-late Forties. What’s more, it looks like the real thing, not a reproduction. Rope dates from 1948, the same year that Avery made “March at a Table,” a copy of which hangs in the Teachout Museum. Hence it’s well within the realm of possibility that I saw exactly what I thought I saw.

Why was I surprised? Because one rarely if ever runs across important modern American paintings in Hollywood movies. When a painting is seen in some millionaire’s living room, it’s almost always a fairly obvious copy of a French Impressionist or post-impressionist canvas….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Zounds! Madam, you had no taste when you married me!”

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, The School for Scandal

TT: You never know

Ann Althouse has been blogging about…well, I’ll let her do the explaining:

I inherited a big stack of record albums that my father bought in the 1950s and 60s and that were part of the home I grew up in. I didn’t really understand what I was hearing and what these things meant to my father, who has been gone a long time.

I decided to listen to one album at a time–not that I’ll endure all of them–and see what I think. I don’t expect to recall my childhood memories or to reconstruct the inner life of the man who existed in ways that couldn’t be understood by me at the time. I don’t expect anything, really. The idea is simply to encounter these albums, because I have them, because he bought them, and because I know they have meaning, even though I don’t think it is possible to find that meaning.

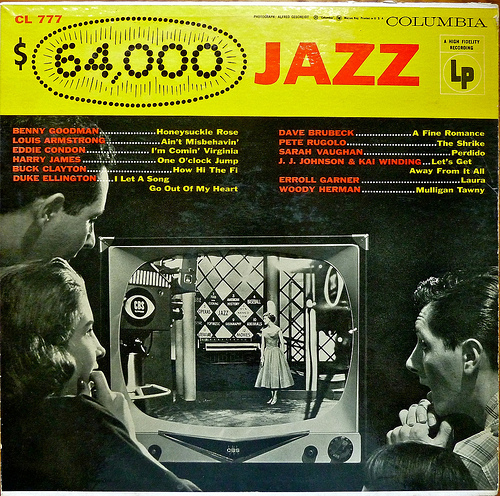

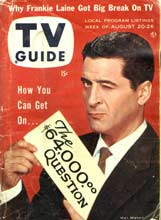

One of Ann’s postings is about $64,000 Jazz, an album that my father also owned. Originally issued on Columbia in 1955, it was occasioned by the popular success of The $64,000 Question, a prime-time quiz that aired on CBS from 1955 to 1958. The first of the big-money game shows, The $64,000 Question was so widely viewed that it actually displaced I Love Lucy as America’s most popular TV series, the first and only show ever to do so. The Rev. Alvin L. Kershaw, an Episcopal minister, won $32,000 in 1955 (the equivalent of $278,810 today) answering questions about jazz. Columbia thereupon released $64,000 Jazz, an anthology of performances by twelve of the label’s top-selling jazz artists.

One of Ann’s postings is about $64,000 Jazz, an album that my father also owned. Originally issued on Columbia in 1955, it was occasioned by the popular success of The $64,000 Question, a prime-time quiz that aired on CBS from 1955 to 1958. The first of the big-money game shows, The $64,000 Question was so widely viewed that it actually displaced I Love Lucy as America’s most popular TV series, the first and only show ever to do so. The Rev. Alvin L. Kershaw, an Episcopal minister, won $32,000 in 1955 (the equivalent of $278,810 today) answering questions about jazz. Columbia thereupon released $64,000 Jazz, an anthology of performances by twelve of the label’s top-selling jazz artists.

What the show’s unsuspecting viewers didn’t know was that it was rigged, a fact whose disclosure helped to trigger the nationwide scandal that was later portrayed by Robert Redford in Quiz Show. (It’s not known whether Rev. Kershaw, who died in 2001, was one of the crooked contestants.) Not surprisingly, $64,000 Jazz went out of print shortly after the program was cancelled, and eventually it became something of a collector’s item.

Needless to say, I knew none of this in 1968, the year in which I found Columbia CL 777 buried among my father’s old records. What interested me about $64,000 Jazz was the music it contained. I’d only just started listening to jazz, and that summer I borrowed a plywood string bass from the band room of my junior high school and taught myself how to play it. I spent countless hours plucking along with those records, $64,000 Jazz among them, and though I had no way of knowing it then, the course of a large part of my future life was thereby set in stone.

Needless to say, I knew none of this in 1968, the year in which I found Columbia CL 777 buried among my father’s old records. What interested me about $64,000 Jazz was the music it contained. I’d only just started listening to jazz, and that summer I borrowed a plywood string bass from the band room of my junior high school and taught myself how to play it. I spent countless hours plucking along with those records, $64,000 Jazz among them, and though I had no way of knowing it then, the course of a large part of my future life was thereby set in stone.

$64,000 Jazz was the first of my father’s albums to which I listened closely and attentively. It was an exceedingly suitable record for a budding young jazz buff to have discovered, for its twelve tracks, all of them selected and annotated by the legendary producer George Avakian, included now-classic performances by the illustrious likes of Louis Armstrong, the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Eddie Condon, Duke Ellington, Erroll Garner, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Harry James, J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding, and Sarah Vaughan. Listening to these performances, which were cut between 1938 and 1955, introduced me to jazz in all its kaleidoscopic diversity, and persuaded me right from the start of my musical career that I wanted to play not just one kind of jazz, but every kind.

When I started playing piano a couple of years later, I taught myself how to pick out the introduction to Erroll Garner’s version of “Laura,” which I learned from $64,000 Jazz. “Laura,” as it happens, was my father’s favorite song. It would always please him to hear me play it, just as it pleases me that my best friend bears the name of the tune that he loved so much. Alas, I never asked my father about $64,000 Jazz, just as he never discussed jazz with me, and so I will never know what, if anything, the album meant to him.

When I started playing piano a couple of years later, I taught myself how to pick out the introduction to Erroll Garner’s version of “Laura,” which I learned from $64,000 Jazz. “Laura,” as it happens, was my father’s favorite song. It would always please him to hear me play it, just as it pleases me that my best friend bears the name of the tune that he loved so much. Alas, I never asked my father about $64,000 Jazz, just as he never discussed jazz with me, and so I will never know what, if anything, the album meant to him.

He was glad, of course, that I’d taken an interest in the music of his youth, and even more pleased when I started playing it professionally in college. I like to think that he would have been proud of me had he lived long enough to read Pops and Duke. But my father was a difficult man, uneasy in his own skin, and so the two of us never achieved anything remotely approaching intimacy. We simply didn’t have enough in common save for our love of music, though we did manage in the last years of his life to grow somewhat more comfortable with one another. I am–much to my surprise–more like him than I knew.

Forty-five years after the fact, it’s strange to think how powerful and permanent an effect $64,000 Jazz had on me. Not only have I written books about two of the musicians whose music I first heard on $64,000 Jazz, but I actually know George Avakian, with whom I shared a dais just last fall. Eddie Condon’s version of “I’m Comin’ Virginia” was one of the records that I played four years ago at Dick Sudhalter’s memorial service. And when I had to choose a late-Thirties composition by Duke Ellington to discuss in detail in Duke, I picked I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart.

Forty-five years after the fact, it’s strange to think how powerful and permanent an effect $64,000 Jazz had on me. Not only have I written books about two of the musicians whose music I first heard on $64,000 Jazz, but I actually know George Avakian, with whom I shared a dais just last fall. Eddie Condon’s version of “I’m Comin’ Virginia” was one of the records that I played four years ago at Dick Sudhalter’s memorial service. And when I had to choose a late-Thirties composition by Duke Ellington to discuss in detail in Duke, I picked I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart.

The $64,000 Question, however, is all but forgotten today, a footnote to the history of Eisenhower-era pop culture. Though the phrase “the $64,000 question” remains part of the American language, it’s now a stone-dead metaphor, one that I’ve never heard used by anyone much under the age of fifty. As for me, I never saw the show, which went off the air two years before I was born, and to watch a kinescope of The $64,000 Question on YouTube today is to marvel at how anyone could ever have supposed that it was anything other than comprehensively fraudulent.

Even so, I will always be grateful to its makers for having opened the ears of a small-town boy to the sound of jazz–a boy who grew up to play bass in the nightclubs of Kansas City and write the biographies of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Such are the ways of the law of unintended consequences, a law of life that I have now lived long enough to appreciate in all its inscrutable, probability-beggaring splendor.

* * *

To download $64,000 Jazz, go here.

A 1958 episode of The $64,000 Question, hosted by Hal March. The first contestant, Virgil Earp, was Wyatt Earp’s nephew:

TT: Just because

A rare 1976 CBC interview with Paul Desmond, the alto saxophonist of the Dave Brubeck Quartet:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“In marriage, talk occupies most of the time.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, Human All-Too-Human

PROTECTING DETROIT’S ARTWORK IS A JOB FOR DETROIT

“It’s not an ‘argument’ to suggest that anyone who advocates selling off the DIA’s masterpieces is an art-hating philistine. Even if they’re wrong, as I think they are, the sell-the-art crowd is making a morally serious case that can’t be countered by name-calling. How best can it be opposed–and who should be doing the opposing? Any argument to keep Detroit’s masterpieces in Detroit has got to make sense to Detroiters who think that pensions are more important than paintings…”