In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss the complex problem of translating foreign-language plays into English. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Whether they know it or not, most American playgoers owe an incalculably great debt to translators. Were it not for their work, comparatively few of us would be able to enjoy the plays of Chekhov, Ibsen or Molière. They are our lifelines to the wider world of theater. Yet literary translators are the perpetually unsung heroes and heroines of literature. (If you doubt it, try naming a half-dozen of them off the top of your head.) Their indispensable efforts are scarcely ever mentioned in theater reviews save in passing, even though it is in their voices that the vast majority of English-speaking critics, myself included, hear such supreme masterpieces of the playwright’s art as “The Cherry Orchard,” “Hedda Gabler” and “The Misanthrope.”

Yes, translation is by definition an inadequate substitute for being able to read a masterpiece in the original. As Robert Frost famously said, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.” But it’s vastly better than nothing, and sometimes it’s so much better that a first-rate performance of a well-translated play is not a poor makeshift but a profoundly satisfying experience in its own right.

I suspect that most playgoers don’t understand how inexact a science literary translation is. Even the simplest of lines may lend itself to multiple renderings. Take, for instance, Masha’s oft-quoted first line in Chekhov’s “The Seagull.” When Medvedenko asks her why she always wears black, she replies, “I’m in mourning for my life. I’m unhappy.” That, at any rate, is the way the line is translated by Milton Ehre, Michael Frayn, Stephen Mulrine, Tom Stoppard, Jean-Claude van Itallie, Laurence Senelick and Christopher Hampton. But Marian Fell, who prepared the first published English-language version of “The Seagull” in 1912, translated it this way: “I dress in black to match my life. I am unhappy.” It was Constance Garnett who in 1923 came up with something close to our modern version…

These distinctions may seem trivial on the page, but they make a huge difference on the stage, where every consonant counts. Moreover, exactitude is not the same thing as stageworthiness. An effective translation of a play must be speakable. Accurate or not, it’ll feel flat in performance if it doesn’t give an actor something solid to wrap his tongue around.

These distinctions may seem trivial on the page, but they make a huge difference on the stage, where every consonant counts. Moreover, exactitude is not the same thing as stageworthiness. An effective translation of a play must be speakable. Accurate or not, it’ll feel flat in performance if it doesn’t give an actor something solid to wrap his tongue around.

That’s why some of the best translations have been the work of experienced actors. The most spectacular example is Charles Laughton’s English-language version of Bertolt Brecht’s “Life of Galileo,” which he prepared in close collaboration with the author, after which he performed the play in Los Angeles and New York in 1947. Laughton’s version isn’t always precisely faithful to the original, but when I saw it performed last year by New York’s Classic Stage Company, I was amazed to discover how much more theatrical it was than the now-standard translation of David Edgar….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for 2013

TT: Almanac

“We do not live for idle amusement. I would not run round a corner to see the world blow up.”

Henry David Thoreau, “Life Without Principle”

TT: Off to the races

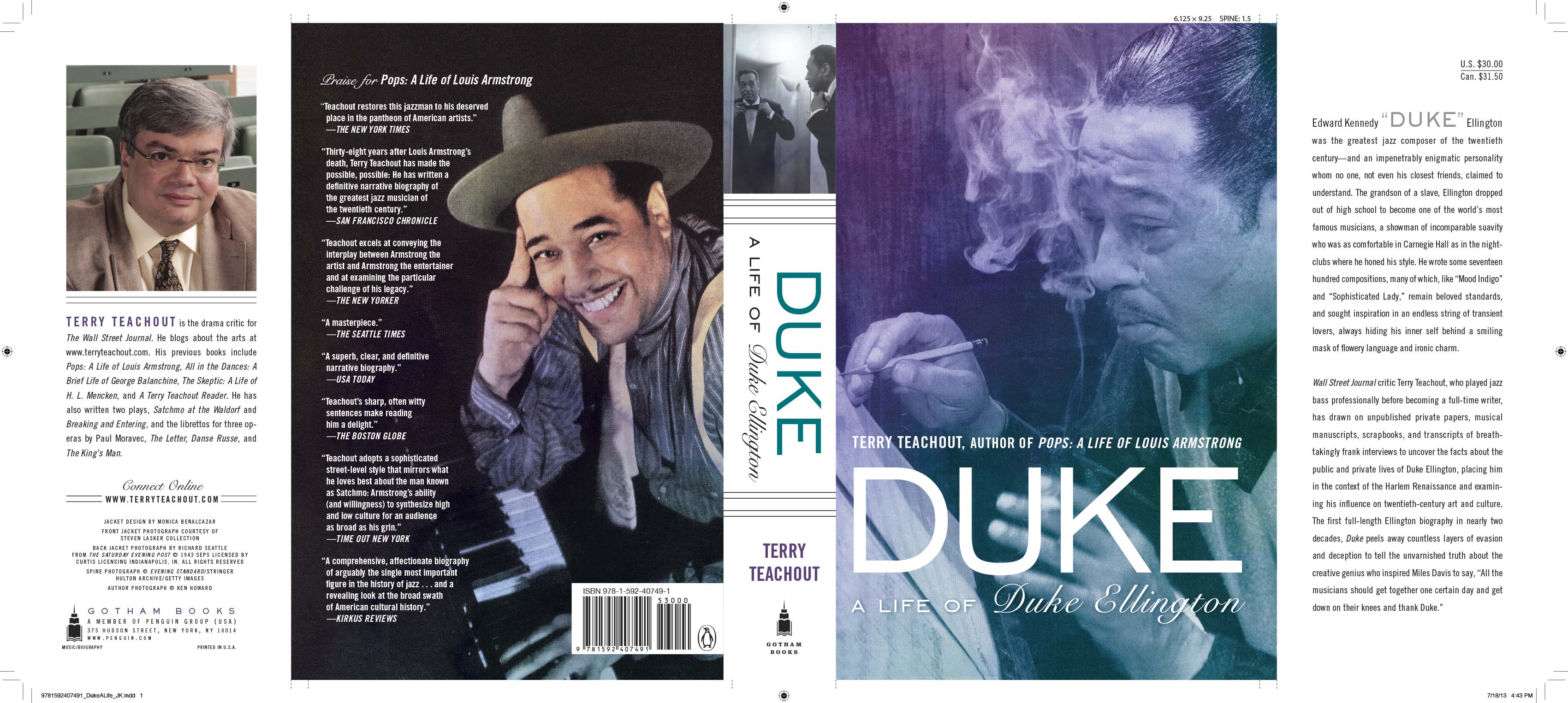

This is the finished dust jacket for Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. I think it’s gorgeous.

While we’re on the subject of Duke, Publishers Weekly has given the book a thumbs-up review. Here’s the money quote:

Teachout neatly balances colorful anecdote with shrewd character assessments and musicological analysis, and he manages to debunk Ellington’s self-mythologizing, while preserving his stature as the man who caught jazz’s ephemeral genius in a bottle.

Thanks much, PW. That’s Duke in a nutshell–and that last phrase is very neat in its own right.

Booklist was similarly enthusiastic and equally quotable, calling Duke “entertaining and valuable” and going on to say:

Though respectful and musically knowing, Teachout presents the famously evasive and not altogether admirable Ellington (among other traits, procrastination, manipulativeness, and incorrigible womanizing) scars and all, including the rarely photographed one (rectified here) on his left cheek, inflicted by his jealous wife. It is Ellington’s breathtakingly enormous musical contribution (1,700 compositions, from short pieces to major suites and sacred music) and his gift for collaboration, albeit often appropriation, that is the fitting focus of this important book.

So far, so good….

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Annie (musical, G, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• The Trip to Bountiful (drama, G, closes Oct. 9, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• The Weir (drama, PG-13, extended through Sept. 15, reviewed here)

IN ASHLAND, OREGON:

• My Fair Lady (musical, G, closes Nov. 3, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN GARRISON, N.Y.:

• All’s Well That Ends Well (Shakespeare, PG-13, closes Aug. 30, reviewed here)

• King Lear (Shakespeare, PG-13, closes Aug. 31, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

• Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike (comedy, PG-13, remounting of off-Broadway production, closes Aug. 25, nearly all performances sold out last week, original production reviewed here)

x

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN CHICAGO:

• Big Lake Big City (comedy, PG-13/R, completely unsuitable for children, closes Aug. 25, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Nobody Loves You (musical, PG-13/R, reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“Most men would feel insulted, if it were proposed to employ them in throwing stones over a wall, and then in throwing them back, merely that they might earn their wages. But many are no more worthily employed now.”

Henry David Thoreau, “Life Without Principle”

TT: Snapshot

The Royal Ballet performs Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces. The score is by Igor Stravinsky:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live.”

Henry David Thoreau, journal entry, August 19, 1851

TT: Lookback

From 2004:

I work at home in a small office-bedroom whose third-floor window looks down on a quiet, tree-lined block of Upper West Side brownstones. The window is to my left, a clothes closet to my right, and over the closet is a sleeping loft. (The ceilings in my apartment are unusually high.) The walls are white, the furniture black, the rug black and tan. I sit on a cheap, creaky swivel chair. My desk is one of those Danish-style slab-and-tube jobs: four shelves, no drawers. The shelf on which I work holds my iBook, a pair of good-quality desktop speakers hooked up to the computer (I often listen to music while I write), a phone-fax-answering machine, an external zip drive, and a tall, sometimes shaky stack of review CDs. My printer is on the bottom shelf. The shelf immediately above eye level holds a few framed pictures, a flashlight (just in case), and two short stacks of review copies and bound galleys of forthcoming books….

Read the whole thing here.