I brought five books to Louisville to read in between rehearsals of The King’s Man, two for professional reasons and three purely for pleasure:

I brought five books to Louisville to read in between rehearsals of The King’s Man, two for professional reasons and three purely for pleasure:

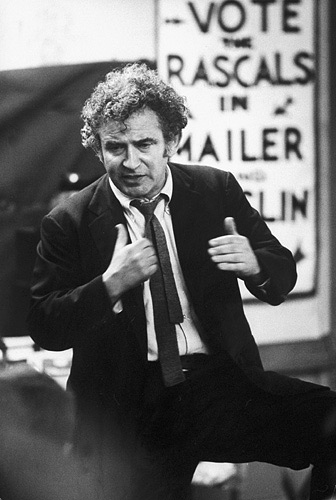

• A set of bound galleys of J. Michael Lennon’s Norman Mailer: A Double Life, which is, as God is my witness, 914 pages long

• A set of bound galleys of The Most of Nora Ephron

• Tom Wolfe’s Back to Blood, which for some reason I didn’t read when it came out last year

• Wesley Stace’s Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (which holds up very well the second time around)

• James Gould Cozzens’ Guard of Honor, my favorite American novel of World War II

We’ll see whether they last me through Sunday. The score so far is four down and one to go….

Archives for October 2013

TT: Hear me talkin’ to ya

Paul Moravec and I are about to report to the studios of WUOL, Louisville’s public radio station, where we’ll be chatting about The King’s Man, our new opera, with Daniel Gilliam, WUOL’s program director (who is himself a composer!). The program, which starts at noon ET, is called Lunch and Listen, and we’ll be bringing along several Kentucky Opera cast members to sing excerpts from the score.

Paul Moravec and I are about to report to the studios of WUOL, Louisville’s public radio station, where we’ll be chatting about The King’s Man, our new opera, with Daniel Gilliam, WUOL’s program director (who is himself a composer!). The program, which starts at noon ET, is called Lunch and Listen, and we’ll be bringing along several Kentucky Opera cast members to sing excerpts from the score.

If you live in the Louisville area, WUOL can be found at 90.5 on your FM dial. To listen on line in streaming audio, go here.

TT: Snapshot

Allegra Kent and Conrad Ludlow dance an excerpt from the second movement of George Balanchine’s Symphony in C. The score is by Georges Bizet:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“I have no desire to prove anything by it. I have never used it as an outlet or a means of expressing myself. I just dance.”

Fred Astaire, Steps in Time

TT: Voices in the air

This is part of a piece that I wrote in 1997:

I like voices. My best friend is a woman whose speaking voice sounded so engaging to me on the phone that I asked her to lunch, sight unseen. (We’ve been friends for seven years now, so I must have been on to something.) Not surprisingly, I also like singers of all kinds, from cool Swedish mezzo-sopranos who specialize in nineteenth-century German lieder to rumbling bassos from Texas who wear white Stetsons and sing sardonic ditties with titles like “My Wife Thinks You’re Dead.” I once wrote a profile of a jazz singer in which I described her voice as sounding like “wild honey with a spoonful of Scotch,” and it was probably the happiest moment of my professional life when I showed up at a nightclub to hear her sing and saw those words printed on a poster hanging outside.

As that story suggests, I tend to think of voices as flavors, so much so that I sometimes refer to certain singers as “strong cheeses”–pungent on the tongue, but tasty once you get used to them. Maria Callas had a voice like that, and so did Billie Holiday; Fats Waller is supposed to have said that Holiday sang as if her shoes pinched. The same is true of many country singers, which is why a lot of otherwise sensible people find country music hard to swallow, and why Nashville record producers now tend to shy away from such distinctive voices in favor of a smoother, blander product which is to authentic country as shrink-wrapped slices of processed cheese food (a phrase which embodies at least two oxymorons) are to a sweaty hunk of fresh Parmesan….

A couple of years before that piece came out, I’d started writing newspaper and magazine articles about jazz and pop musicians, many of them, again not surprisingly, singers with strongly distinctive voices. In the course of the following decade I wrote enthusiastically about, among others, Karrin Allyson, Patricia Barber, Tony Bennett, Mary Foster Conklin, Dena DeRose, Jack Jones, Diana Krall, Alison Krauss, Nancy LaMott, Madeleine Peyroux, John Pizzarelli, Kendra Shank, Luciana Souza, and Weslia Whitfield, subsequently contributing liner notes to some of their albums. By 2003, the year in which I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, I was a passably familiar face in the nightclubs of Manhattan, a state of affairs that I took for granted would continue indefinitely.

A couple of years before that piece came out, I’d started writing newspaper and magazine articles about jazz and pop musicians, many of them, again not surprisingly, singers with strongly distinctive voices. In the course of the following decade I wrote enthusiastically about, among others, Karrin Allyson, Patricia Barber, Tony Bennett, Mary Foster Conklin, Dena DeRose, Jack Jones, Diana Krall, Alison Krauss, Nancy LaMott, Madeleine Peyroux, John Pizzarelli, Kendra Shank, Luciana Souza, and Weslia Whitfield, subsequently contributing liner notes to some of their albums. By 2003, the year in which I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, I was a passably familiar face in the nightclubs of Manhattan, a state of affairs that I took for granted would continue indefinitely.

Alas, my new job soon morphed into something not far from all-consuming. As a result, Julia Dollison, for whose 2005 debut album I had the honor of writing the liner notes, was the last up-and-coming singer in whose career I took a serious and sustained interest. After that I was too busy going to the theater to spend any significant part of my spare time (such as it was) hunting for interesting new voices. What had previously been an important part of my life wound up on the shelf, gathering dust.

All this is prelude to a joyous confession: I recently listened for the first time to a pair of albums by two singers whose work I already knew, and was more than sufficiently impressed to want to tell you about them. If I were still writing pop profiles, I’d call an editor. Since I’m not, these brief plugs will have to suffice:

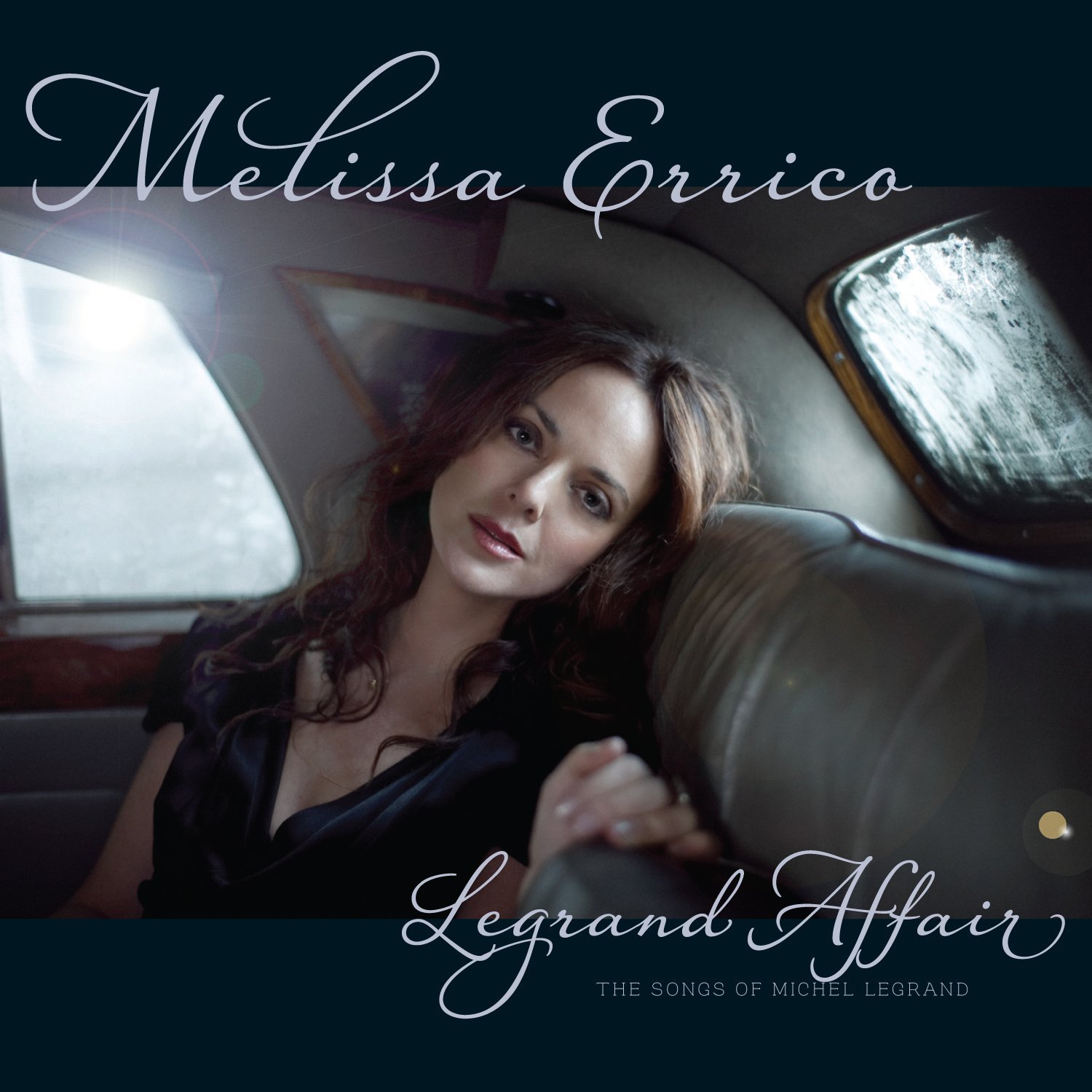

• Melissa Errico’s Legrand Affair, which Ghostlight Records put out two years ago, is a collection of fifteen romantic ballads composed, arranged, and conducted by Michel Legrand and accompanied by the Brussels Philharmonic. If you keep up with the musical-comedy scene, you won’t need to be told that Errico is one of the most prodigally talented theater singers in town, and that her career hit a deep pothole earlier this year when a vocal-cord hemorrhage forced her out of the cast of Classic Stage Company’s off-Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Passion not long after the show opened. (She has since written with moving candor about this terrifying experience on her blog.)

• Melissa Errico’s Legrand Affair, which Ghostlight Records put out two years ago, is a collection of fifteen romantic ballads composed, arranged, and conducted by Michel Legrand and accompanied by the Brussels Philharmonic. If you keep up with the musical-comedy scene, you won’t need to be told that Errico is one of the most prodigally talented theater singers in town, and that her career hit a deep pothole earlier this year when a vocal-cord hemorrhage forced her out of the cast of Classic Stage Company’s off-Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Passion not long after the show opened. (She has since written with moving candor about this terrifying experience on her blog.)

I praised Errico’s performance in the Journal succinctly but emphatically: “Ms. Errico has never before had the opportunity to play so fine a role in New York, and she effortlessly proves her worth: I’ve never seen or heard a better Clara, Audra McDonald included.” Even so, I wasn’t prepared for the impact that Legrand Affair made on me–an impact that is heightened by the elegance with which Errico uses her perfectly placed alto-flute voice. You won’t hear any Broadway-baby belting on this album, whose keynote is a delicacy and restraint that allows the intense feelings of songs like “What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?” and “You Must Believe in Spring” to speak for themselves instead of being pushed across the counter like a short order. While the sheer musicality of Errico’s singing is equally impressive, Legrand Affair is self-evidently the work of a true singer-actor. Every emotion–and every word–tells.

I rejoice to report that Errico is singing again. Celebrate her good fortune by listening to Legrand Affair.

• The Great City, Hilary Gardner’s first solo album, is a self-produced CD consisting of eleven tunes about life in New York. Gardner, a jazz-flavored balladeer who grew up in rural Alaska, then moved to the Big Apple, is best known for having sung in the pit of Come Fly Away, Twyla Tharp’s not-quite-successful 2010 jukebox musical set to the music of Frank Sinatra. I very much liked her singing when I saw the show three years ago, but that was the last I heard of her until a copy of The Great City turned up in my mailbox the other day. I got a chance to listen to it when I found myself commuting each morning from suburban Louisville to the downtown hall where Kentucky Opera is rehearsing The King’s Man. I popped The Great City into the CD player of my rental car and realized within seconds that I’d stumbled across an absolutely first-class singer.

• The Great City, Hilary Gardner’s first solo album, is a self-produced CD consisting of eleven tunes about life in New York. Gardner, a jazz-flavored balladeer who grew up in rural Alaska, then moved to the Big Apple, is best known for having sung in the pit of Come Fly Away, Twyla Tharp’s not-quite-successful 2010 jukebox musical set to the music of Frank Sinatra. I very much liked her singing when I saw the show three years ago, but that was the last I heard of her until a copy of The Great City turned up in my mailbox the other day. I got a chance to listen to it when I found myself commuting each morning from suburban Louisville to the downtown hall where Kentucky Opera is rehearsing The King’s Man. I popped The Great City into the CD player of my rental car and realized within seconds that I’d stumbled across an absolutely first-class singer.

Like Melissa Errico, Gardner has a cool, smooth-surfaced voice, one whose clarinet-like timbre is tinged with a quiet note of knowing wryness. She swings effortlessly without making a big deal of it, and she has a knack for hunting down off-center tunes like Tom Waits’ “Drunk on the Moon” and Nellie McKay’s “Manhattan Avenue.” Yet she’s just as adept at making something fresh and surprising out of an oft-heard chestnut like “Autumn in New York” (performed here, needless to say, with the rarely sung verse). The band is outstanding–I was much taken with the discreet but telling use of Jon Cowherd’s Hammond organ and Randy Napoleon’s guitar–and the uncredited charts set off Gardner’s vocals to lovely effect.

You can order The Great City by going here. Do so.

TT: The rule of “k”

“Words with a k in it are funny. Alka-Seltzer is funny. Chicken is funny. Pickle is funny. All with a k. Ls are not funny. Ms are not funny.” So, at any rate, says one of the characters in Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys, an aged, vastly experienced vaudevillian who, like his creator, ought to know. This familiar comic apophthegm is of immediate relevance to Kentucky Opera‘s revival of Danse Russe, which Paul Moravec and I are rehearsing in Louisville, where it will share a double bill this weekend with The King’s Man, our latest opera.

“Words with a k in it are funny. Alka-Seltzer is funny. Chicken is funny. Pickle is funny. All with a k. Ls are not funny. Ms are not funny.” So, at any rate, says one of the characters in Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys, an aged, vastly experienced vaudevillian who, like his creator, ought to know. This familiar comic apophthegm is of immediate relevance to Kentucky Opera‘s revival of Danse Russe, which Paul Moravec and I are rehearsing in Louisville, where it will share a double bill this weekend with The King’s Man, our latest opera.

Danse Russe, premiered in Philadelphia two years ago, is a backstage comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring. Even though it’s a full-fledged opera, much of it feels like a musical, which puts unusual demands on the four members of the cast, who play Serge Diaghilev, Pierre Monteux, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Igor Stravinsky. Classical singers are trained to emphasize vowels, but musical comedy is all about consonants. “You’re going to rise or fall on your consonants, guys–especially t and k,” I explained to John Arnold, Sergio Gonzalez, Brad Raymond, and Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek, our four singers. “T will make your lines intelligible to the audience, and k will give them comic energy.”

To the latter end, I took the singers backstage and shared with them the Infallible Double-Secret Comic Energy Warm-Up Phrase, an unequivocally obscene four-word line that is spoken by the umpire in this scene from Ron Shelton’s Bull Durham. (The line can also be found here.) “That’s the secret,” I said. “Repeat that line ten times in a row just before you go on stage, and I absolutely guarantee that all of your ks and hard cs will pop right out.”

To the latter end, I took the singers backstage and shared with them the Infallible Double-Secret Comic Energy Warm-Up Phrase, an unequivocally obscene four-word line that is spoken by the umpire in this scene from Ron Shelton’s Bull Durham. (The line can also be found here.) “That’s the secret,” I said. “Repeat that line ten times in a row just before you go on stage, and I absolutely guarantee that all of your ks and hard cs will pop right out.”

They did–and they did.

As I returned to the auditorium, Frances Rabalais, our assistant stage manager, took me aside and fixed me with what I think was probably meant to be a fishy stare.

“Just what were you doing back there?” she asked, trying–not very successfully–to suppress a grin.

“It’s a professional secret,” I replied.

TT: Lookback

From 2003:

I got a call yesterday from a fact checker at The New Yorker. He was working on a piece that made reference to H.L. Mencken, and very apologetically asked me if I could perhaps help him by answering two questions (one was simple, the other subtle). I told him that Mencken would have approved of his labors, which is true. Mencken did quite a bit of writing for The New Yorker in the Thirties and Forties, and referred admiringly to its fact-checking department as “Ross’ goons” (Harold Ross being, of course, the magazine’s founding editor and resident tutelary spirit).

That call filled me with nostalgia. As anyone knows who’s been in journalism for more than the past 20 minutes or so, fact checking is an increasingly lost art….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Most trends exist because they’re permitted to exist and have not been slaughtered.”

Edward Albee, interviewed by Linda Leseman (The Believer, Sept. 2013)