In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss the complex problem of translating foreign-language plays into English. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Whether they know it or not, most American playgoers owe an incalculably great debt to translators. Were it not for their work, comparatively few of us would be able to enjoy the plays of Chekhov, Ibsen or Molière. They are our lifelines to the wider world of theater. Yet literary translators are the perpetually unsung heroes and heroines of literature. (If you doubt it, try naming a half-dozen of them off the top of your head.) Their indispensable efforts are scarcely ever mentioned in theater reviews save in passing, even though it is in their voices that the vast majority of English-speaking critics, myself included, hear such supreme masterpieces of the playwright’s art as “The Cherry Orchard,” “Hedda Gabler” and “The Misanthrope.”

Yes, translation is by definition an inadequate substitute for being able to read a masterpiece in the original. As Robert Frost famously said, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.” But it’s vastly better than nothing, and sometimes it’s so much better that a first-rate performance of a well-translated play is not a poor makeshift but a profoundly satisfying experience in its own right.

I suspect that most playgoers don’t understand how inexact a science literary translation is. Even the simplest of lines may lend itself to multiple renderings. Take, for instance, Masha’s oft-quoted first line in Chekhov’s “The Seagull.” When Medvedenko asks her why she always wears black, she replies, “I’m in mourning for my life. I’m unhappy.” That, at any rate, is the way the line is translated by Milton Ehre, Michael Frayn, Stephen Mulrine, Tom Stoppard, Jean-Claude van Itallie, Laurence Senelick and Christopher Hampton. But Marian Fell, who prepared the first published English-language version of “The Seagull” in 1912, translated it this way: “I dress in black to match my life. I am unhappy.” It was Constance Garnett who in 1923 came up with something close to our modern version…

These distinctions may seem trivial on the page, but they make a huge difference on the stage, where every consonant counts. Moreover, exactitude is not the same thing as stageworthiness. An effective translation of a play must be speakable. Accurate or not, it’ll feel flat in performance if it doesn’t give an actor something solid to wrap his tongue around.

These distinctions may seem trivial on the page, but they make a huge difference on the stage, where every consonant counts. Moreover, exactitude is not the same thing as stageworthiness. An effective translation of a play must be speakable. Accurate or not, it’ll feel flat in performance if it doesn’t give an actor something solid to wrap his tongue around.

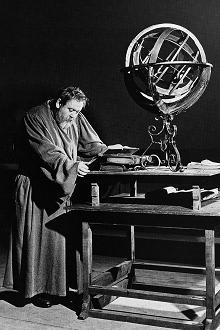

That’s why some of the best translations have been the work of experienced actors. The most spectacular example is Charles Laughton’s English-language version of Bertolt Brecht’s “Life of Galileo,” which he prepared in close collaboration with the author, after which he performed the play in Los Angeles and New York in 1947. Laughton’s version isn’t always precisely faithful to the original, but when I saw it performed last year by New York’s Classic Stage Company, I was amazed to discover how much more theatrical it was than the now-standard translation of David Edgar….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog