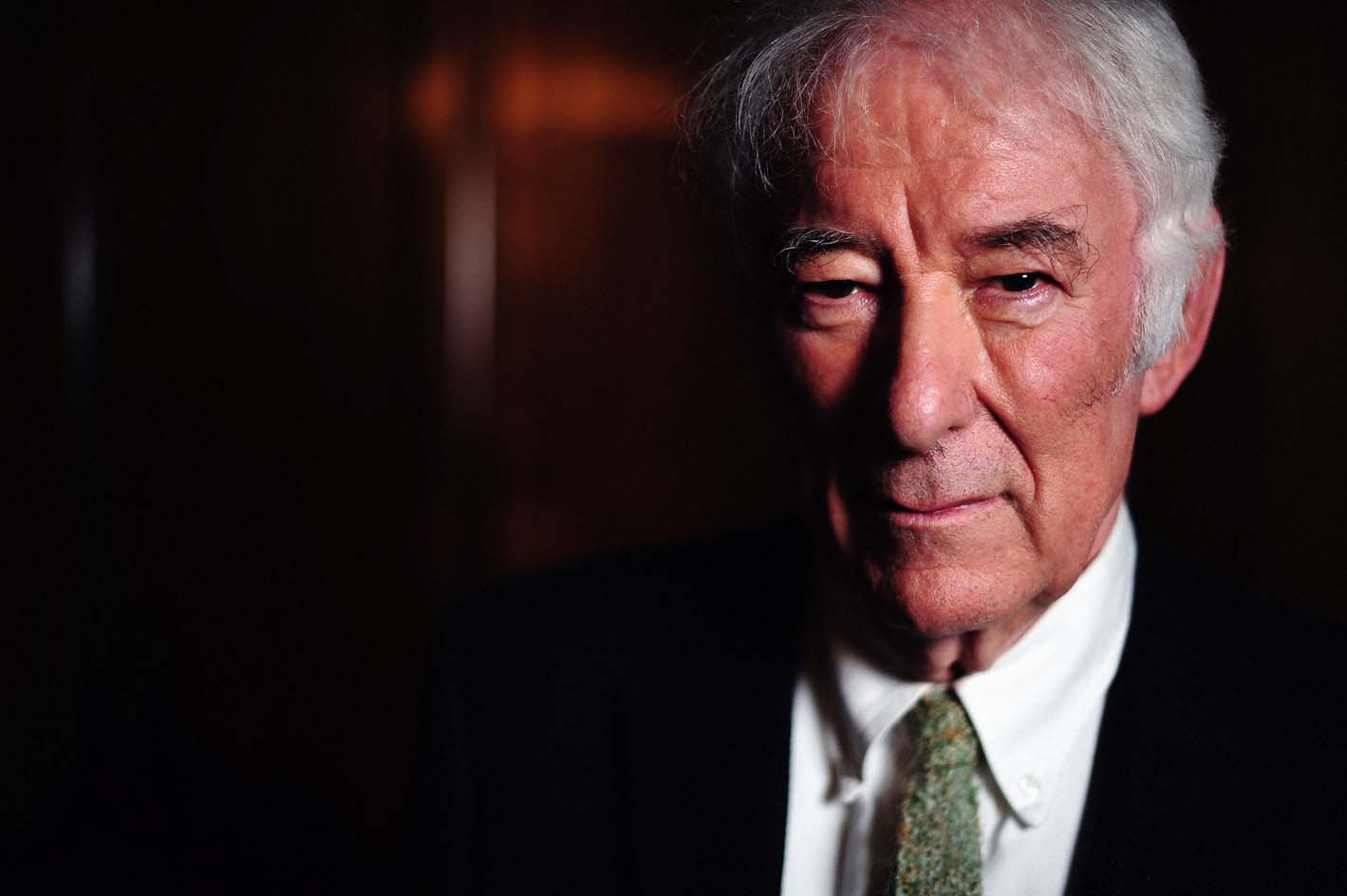

In memory of Seamus Heaney, the great Irish poet who died today, here is my 2011 Wall Street Journal review of American Players Theatre’s production of The Cure at Troy, adapted by Heaney from Sophocles’ Philoctetes.

* * *

Professional productions of the Greek tragedies seem to be growing less common in America–the last time I reviewed one was in 2008–and so American Players Theatre’s revival of “The Cure at Troy,” Seamus Heaney’s adaptation of Sophocles’ “Philoctetes,” is of interest for that reason alone. But APT’s staging, directed by David Frank, the company’s artistic director, is no curiosity. It is, in fact, an overwhelming theatrical experience, a show whose emotional impact is nothing short of shattering. If you’re fortunate enough to see it, you’ll remember it for as long as you remember anything.

“Philoctetes,” in which Sophocles dramatized the myth of the wounded Greek warrior (David Daniel) who was deserted by Odysseus (Jonathan Smoots) and his comrades, was largely forgotten save by classicists when Mr. Heaney published his English-language adaptation in 1991, four years before he won the Nobel Prize. “The Cure at Troy” is a masterly piece of versification, at once unpretentious in diction and elevated in tone. Without distorting the play’s meaning, Mr. Heaney has subtly emphasized its continuing relevance, placing lines in the mouths of the chorus that liken the furious Philoctetes’ self-consuming desire for revenge to the irredentist madness of Northern Ireland, the land of the poet’s birth: “So hope for a great sea-change/On the far side of revenge./Believe that a further shore/Is reachable from here.”

“Philoctetes,” in which Sophocles dramatized the myth of the wounded Greek warrior (David Daniel) who was deserted by Odysseus (Jonathan Smoots) and his comrades, was largely forgotten save by classicists when Mr. Heaney published his English-language adaptation in 1991, four years before he won the Nobel Prize. “The Cure at Troy” is a masterly piece of versification, at once unpretentious in diction and elevated in tone. Without distorting the play’s meaning, Mr. Heaney has subtly emphasized its continuing relevance, placing lines in the mouths of the chorus that liken the furious Philoctetes’ self-consuming desire for revenge to the irredentist madness of Northern Ireland, the land of the poet’s birth: “So hope for a great sea-change/On the far side of revenge./Believe that a further shore/Is reachable from here.”

Not surprisingly, “The Cure at Troy” was taken up by drama companies throughout the English-speaking world, but it has been a number of years since it last received a noteworthy American production. Fortunately, this modern-dress version, which is being performed by a cast of six in APT’s gemlike 200-seat thrust-stage indoor theater, is completely worthy of the play. Mr. Frank and Robert Morgan, who designed the set and costumes, have presented “The Cure at Troy” with the utmost simplicity. The scene is a barrel-strewn waterfront that bears an eerie resemblance to a jigsaw puzzle. In this desolate space, Messrs. Daniel and Smoots vie for the loyalty–and the soul–of Neoptolemus (Paul Hurley), a young soldier who is torn between patriotic duty and personal honor. No more than Sophocles or Mr. Heaney does Mr. Frank seek to simplify Neoptolemus’ dilemma, and it is precisely because of this hard honesty that the divine illumination that ends the play carries the wrenching force of true revelation.

Three of the cast members are part of APT’s resident ensemble, and they give performances so compelling that you’ll want to hold your breath each time they speak. Mr. Daniel’s Philoctetes is a coolly urbane gentleman-warrior whom pain has reduced to a shrieking shadow of himself. Mr. Smoots’s Odysseus is a rich-voiced cynic who is quick to heed the reassuring call of expediency. And Sarah Day, the leader of the three-woman chorus, narrates the unfolding tragedy with the world-weary wisdom of one who knows in her bones that understanding and forgiveness are not the same thing.

All three, like Mr. Frank and the other members of the cast and production team, have placed their talents wholly in the play’s service. As a result, Mr. Heaney’s most telling lines come across so clearly, even nakedly, that you can hear the audience gasping with the shock of recognition (“War has an appetite/For human goodness but it won’t touch the bad”). Anyone who doubts the permanent significance of the classics should pay heed to those gasps. It says much about man’s unchanging nature–and the miraculous power of art to efface time and space–that they should be provoked by a play that was first performed more than 2,000 years ago.

Archives for August 30, 2013

TT: A Wisconsin tragedy

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I file the first of two dispatches from Wisconsin’s American Players Theatre. This week I report on the company’s productions of All My Sons, Antony and Cleopatra, and Dickens in America. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“All My Sons,” the 1947 play in which Arthur Miller told the tragic tale of a small-town family that has lived with lies for too long, isn’t a masterpiece–it’s too preachy for that–but it’s written with an uncomplicated plainness that makes much of Miller’s later work, “Death of a Salesman” included, sound overwrought by comparison. Do it naturalistically and straightforwardly and you can’t miss. Add a pinch of understated imagination and the results will be even better. William Brown’s American Players Theatre production scores big on both counts, and also features a superior cast led by Jonathan Smoots and Sarah Day, two veteran members of APT’s permanent core ensemble who outdo themselves this time around.

“All My Sons,” the 1947 play in which Arthur Miller told the tragic tale of a small-town family that has lived with lies for too long, isn’t a masterpiece–it’s too preachy for that–but it’s written with an uncomplicated plainness that makes much of Miller’s later work, “Death of a Salesman” included, sound overwrought by comparison. Do it naturalistically and straightforwardly and you can’t miss. Add a pinch of understated imagination and the results will be even better. William Brown’s American Players Theatre production scores big on both counts, and also features a superior cast led by Jonathan Smoots and Sarah Day, two veteran members of APT’s permanent core ensemble who outdo themselves this time around.

What makes their performances so striking is the doubleness of character that they suggest. Mr. Smoots plays Joe Keller, a factory-owning wartime profiteer whose corner-cutting, which led to the deaths of 21 American pilots, is about to be unmasked. On the surface he’s an ingratiating back-slapper, but scratch his good cheer and you’ll find stark terror. Not so Kate (Ms. Day), his wife, whose grandmotherly exterior conceals a Medea-like hardness of soul that is nothing short of terrifying….

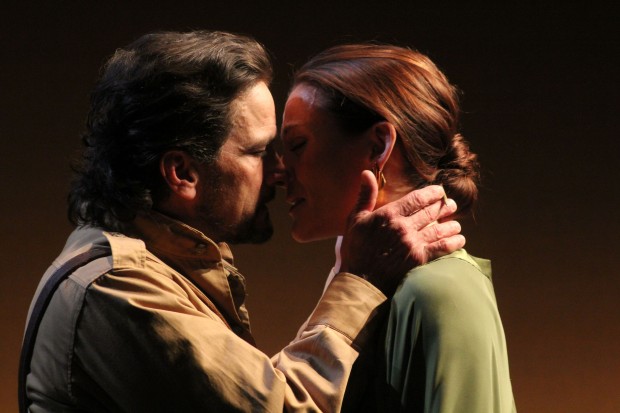

Small-cast Shakespeare stagings are very much the fashion these days, and Kate Buckley’s “Antony and Cleopatra” is one of the best I’ve seen, a seven-actor chamber adaptation by Ms. Buckley and James DeVita in which everything peripheral to the central relationship between the title characters (incisively played by Mr. DeVita and Tracy Michelle Arnold) has been ruthlessly and creatively stripped away. What emerges from the cutting is a terse, tightly focused parable of the power–and price–of physical obsession….

Small-cast Shakespeare stagings are very much the fashion these days, and Kate Buckley’s “Antony and Cleopatra” is one of the best I’ve seen, a seven-actor chamber adaptation by Ms. Buckley and James DeVita in which everything peripheral to the central relationship between the title characters (incisively played by Mr. DeVita and Tracy Michelle Arnold) has been ruthlessly and creatively stripped away. What emerges from the cutting is a terse, tightly focused parable of the power–and price–of physical obsession….

Mr. DeVita, it turns out, is as good a playwright as he is an actor. His “Dickens in America,” for instance, is a one-man show in the style of Hal Holbrook’s “Mark Twain Tonight!” whose conceit is ingenious: The audience is invited to imagine that it’s present at Charles Dickens’ last public reading of excerpts from his novels, in the course of which he interpolates reminiscences that are shadowed by his awareness of his fast-approaching death. James Ridge is a slender, sprightly Dickens…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: More than a radio star

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I talk about the artistry of Marian McPartland. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When Marian McPartland died last week at the age of 95, the obituaries devoted roughly equal time to her career as a jazz pianist, her second career as the founder and longtime host of NPR’s “Piano Jazz” and the fact that she was a woman. That’s fair enough: “Piano Jazz” was the most influential jazz program in the history of American network radio, and McPartland came to fame at a time when you could still count the number of successful women jazz instrumentalists on the fingers of one hand. But the flood of tributes failed to make clear what her admirers had always known, which was that she was a performer first and foremost, a soloist of strong personality and real quality whose shimmering, iridescent harmonies were instantly distinctive. “Piano Jazz” may have made McPartland famous, but it was her playing that made her important.

McPartland always made a point of playing duets with her guests on “Piano Jazz” (on which she interviewed everyone from Dave Brubeck to Steely Dan). The chameleon-like ease with which she accommodated their varied styles could suggest to casual listeners that she had no style of her own. Nothing could have been further from the truth: Never for a moment did she submerge her own quiet yet unmistakable individuality. Nor should she have done so, for she worked unremittingly hard to develop it, much harder than most of her fans realized.

Born in England in 1918, McPartland was a classically trained prodigy who became interested in jazz as a teenager. Not until 1944, though, did she work for the first time with an American jazzman, the cornetist Jimmy McPartland, a Bix Beiderbecke protégé whom she married and with whom she moved to the U.S. after World War II. There she heard bebop and turned herself into a thoroughly modern jazz soloist. In 1952 McPartland and her trio began an eight-year residency at the Hickory House, a popular New York restaurant that was one of Duke Ellington’s favorite hangouts. At length she got up the nerve to ask Ellington what he thought of her playing. His reply was elegantly and charcteristically enigmatic: “You play so many notes.” Eventually it hit McPartland that he wasn’t paying her a compliment: “After a while I thought, ‘He probably is telling me I’m playing too many.’ It was one of the best criticisms I ever had.”…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Marian McPartland plays her arrangement of Bix Beiderbecke’s “In a Mist” in 1974:

TT: Almanac

“No life is all bleak. Even in Primo Levi’s camp, there were small sources of hope: you got on the good work detail, or you got on the right soup line. That’s what’s so gorgeous about humanity. It doesn’t matter how bleak our daily lives are, we still fight for the light. I think that’s our divinity. We lean into love, even in the most hideous circumstances. We manage to hope.”

Mary Karr, interview, The Paris Review (Winter 2009)