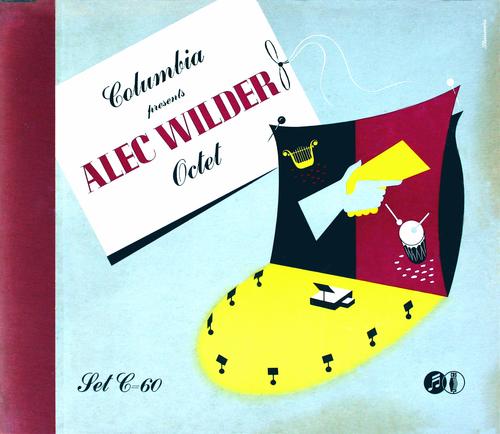

• I don’t often write liner notes nowadays, but I’m making an exception for Hep Records‘ latest project, an eagerly awaited two-CD set that will contain, among other things, the complete recordings of the Alec Wilder Octet, which were originally released on 78 and since then have never been reissued in their entirety.

• I don’t often write liner notes nowadays, but I’m making an exception for Hep Records‘ latest project, an eagerly awaited two-CD set that will contain, among other things, the complete recordings of the Alec Wilder Octet, which were originally released on 78 and since then have never been reissued in their entirety.

If you don’t know who Wilder was, you might want to take a look at this piece, which I wrote for the New York Times Book Review in 1996. If you’ve never heard any of his octet recordings, I suggest that you listen to A Debutante’s Diary, the group’s 1939 recording debut, which will give you a very clear idea of what it sounded like.

I’ll let you know when the Hep set is available. I can’t recommend it too strongly.

• The Winter Park Institute of Rollins College, my sometime home away from home in central Florida, has invited me to spend another month-long stint as a scholar in residence next February. I plan to engage in various public activities while I’m in Winter Park, of which this lecture will likely be the most spectacular. In addition to talking about Duke Ellington and his legacy, I’ll be accompanied by a hand-picked big band that will play selections from the master’s oeuvre. Mark your calendar!

• Paul Moravec and I are hard at work on The King’s Man, our third opera, which opens at Louisville’s Kentucky Opera on October 11. I recently took time out from revising the libretto to write a short program note for the premiere. I thought it might interest you.

* * *

Everybody in America knows who Benjamin Franklin was, more or less, and most people even have a pretty good idea of what he looked like. But William Franklin, Ben’s illegitimate son, is known only to those who are well read in American history, even though the story of his stormy relationship with his famous father is a fascinating and disturbing tale. Unlike Ben, William was a Tory who chose to remain loyal to King George III throughout the Revolutionary War, a decision that got him tossed into prison and nearly cost him his life. It also led to a permanent break between father and son, who saw each other only once more after William fled to England in 1782. Their final meeting, and the complicated events that led up to it, are what The King’s Man is about.

Paul Moravec, my operatic collaborator, has long been fascinated by Ben Franklin, so much so that he composed a piece called Useful Knowledge that is based on his writings. When we decided to write a companion piece to Danse Russe, our second opera, a backstage comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring, Paul suggested that we might look to Franklin as a possible subject. It soon became clear to both of us that Ben’s break with William was not just dramatic but positively operatic. While my libretto is a fictionalized account of their quarrel that takes liberties with the facts, it is firmly rooted in historical truth. To be sure, we don’t know all that much about the particulars of the two men’s relationship–neither one of them left behind anything like a frank account of how they felt about one another–I think the way that we portray them in The King’s Man is entirely plausible. Few things, after all, are as fraught with tension and resentment as the relationship between a father of genius and a son who is merely talented, and that is what Paul and I have sought to explore.

Paul Moravec, my operatic collaborator, has long been fascinated by Ben Franklin, so much so that he composed a piece called Useful Knowledge that is based on his writings. When we decided to write a companion piece to Danse Russe, our second opera, a backstage comedy about the making of The Rite of Spring, Paul suggested that we might look to Franklin as a possible subject. It soon became clear to both of us that Ben’s break with William was not just dramatic but positively operatic. While my libretto is a fictionalized account of their quarrel that takes liberties with the facts, it is firmly rooted in historical truth. To be sure, we don’t know all that much about the particulars of the two men’s relationship–neither one of them left behind anything like a frank account of how they felt about one another–I think the way that we portray them in The King’s Man is entirely plausible. Few things, after all, are as fraught with tension and resentment as the relationship between a father of genius and a son who is merely talented, and that is what Paul and I have sought to explore.

The King’s Man was specifically written to be performed in tandem with Danse Russe. Yes, Danse Russe is a giddy farce with touches of tenderness and The King’s Man is a dark domestic drama, but both works are one-act historical operas of similar length that are performed by the same vocal and instrumental forces. We hope they add up to a satisfying night at the theater–one that is both entertaining and thought-provoking.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog