I flew from New York to San Francisco last Tuesday, and more than once along the way I wondered whether I should have stayed home. Not only was San Francisco International Airport still convulsed by a plane crash that had closed one of the runways, but the aircraft on which I was flying was afflicted by a broken air conditioner and a broken navigational computer. We spent more than an hour sweating on the tarmac in New York, and arrived on the West Coast four and a half hours late.

All this made me grateful–sort of–that Mrs. T decided to stay home instead of accompanying me to California and Oregon. I wouldn’t have wanted to put her through a day like that. But no sooner did I extract myself from the hotel’s hot tub and drive out to Orinda’s California Shakespeare Theater on Wednesday to see Romeo and Juliet with a friend than I forgot all about my (admittedly minor) ordeal.

All this made me grateful–sort of–that Mrs. T decided to stay home instead of accompanying me to California and Oregon. I wouldn’t have wanted to put her through a day like that. But no sooner did I extract myself from the hotel’s hot tub and drive out to Orinda’s California Shakespeare Theater on Wednesday to see Romeo and Juliet with a friend than I forgot all about my (admittedly minor) ordeal.

While outdoor theater is sometimes more of a nuisance than it’s worth, Cal Shakes, a five-hundred-forty-five-seat amphitheater located atop a hill not far from the city, is one of America’s most idyllic performing spaces. Seeing a play there can take you out of yourself faster than just about anything I know, and that’s exactly what happened to me.

Alas, I never seem to know what time it is when I’m on the West Coast, which I proved anew by forgetting that Romeo and Juliet started at seven-thirty, not eight. Being the compulsively early type, I pulled into the parking lot at seven-thirty-five, noticed at once that nobody else was doing the same thing, and hastened shamefacedly to the box office, where I discovered, entirely to my surprise, that the curtain was being held for my friend and me. We sat down and the show started at once. Sometimes it’s good to be Guffman.

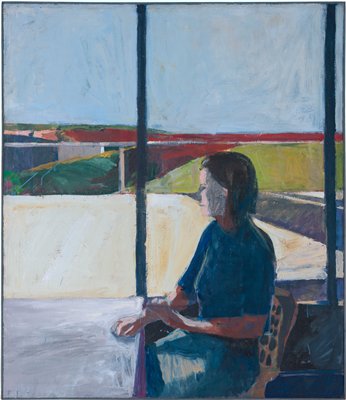

I took Thursday off and went to the de Young Museum to see Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966, a very important exhibition of some 130-odd paintings and drawings that, not altogether surprisingly, won’t be traveling to New York, or anywhere else other than the Palm Springs Art Museum. Diebenkorn, who died in 1993, was one of this country’s greatest painters, but his greatness has yet to be universally acknowledged, and I suspect that one reason for this failure of perception is that he was a West Coast artist who spent most of his adult life in California, at a time when New York City was universally regarded as the creative center of American art. When it comes to art, the East Coast has always had trouble taking the West Coast seriously, just as New Yorkers are reluctant to admit that theater in Chicago is at least as good as theater in Manhattan. It’s one of the many ways we have of being provincial.

It happens that Mrs. T and I saw another first-class Diebenkorn show, “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Years,” on our last visit to California. I wrote about it not long afterward in The Wall Street Journal. Here’s part of what I said:

It happens that Mrs. T and I saw another first-class Diebenkorn show, “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Years,” on our last visit to California. I wrote about it not long afterward in The Wall Street Journal. Here’s part of what I said:

Mr. Diebenkorn, who died in 1993, waged a lifelong “battle” with abstraction. He started out as a gifted Abstract Expressionist painter. In 1955 he suddenly embraced representation, turning out dozens of figurative paintings that translate the language of Matisse into a wholly personal, semiabstract style. Then, in the Ocean Park series, he made a decisive return to total abstraction, in the process creating the most original works of his career.

To chart Mr. Diebenkorn’s stylistic development is to be reminded of the near-overwhelming power of the idea of abstraction in the 20th century. It was even felt by artists who, like Pierre Bonnard and Fairfield Porter, never produced an abstract painting in their lives, but were nonetheless influenced by the way in which practitioners of abstraction created what Mr. Diebenkorn called “invented landscapes,” nonobjective images that evoked the world of tangible reality while steering clear of literal representation….

The Berkeley Years covers the second phase of Diebenkorn’s development. Most of the paintings in the show are representational, and most of the best ones are landscapes in which the human figure is either absent or secondary. Even when Diebenkorn painted a person–almost always a woman–he tended to be shy about showing her face. I wonder whether this detachment might have contributed further to the fact that he has never been as popular as he ought to be.

The Berkeley Years covers the second phase of Diebenkorn’s development. Most of the paintings in the show are representational, and most of the best ones are landscapes in which the human figure is either absent or secondary. Even when Diebenkorn painted a person–almost always a woman–he tended to be shy about showing her face. I wonder whether this detachment might have contributed further to the fact that he has never been as popular as he ought to be.

In any case, The Berkeley Years is an incredibly rich and soul-satisfying show, defective only in the decision of the curator not to hang any of Diebenkorn’s prints (he was, as Mrs. T and I have reason to know, a master printmaker). In every other way, the range and force of his prodigious output are displayed with discernment, and if you can’t get out to San Francisco or Palm Springs to see it, the superlative catalogue will give you a clear idea of what you’re missing.

![]() I love to visit San Francisco, though I don’t think I’d ever want to live there. As much as I like fog, the perpetually damp climate doesn’t suit my tastes. Neither does the city’s comfortably hip vibe. It is, I incline to think, a place rather too pleased with itself for its own good–but, then, it has much to be pleased about, above all its near-unrivaled natural beauty. I never get tired of looking at San Francisco. And a city that can boast of a museum like the de Young (though the building is better than the collection it houses) or an orchestra like Michael Tilson Thomas’ San Francisco Symphony needn’t apologize to anybody about anything, culturally speaking.

I love to visit San Francisco, though I don’t think I’d ever want to live there. As much as I like fog, the perpetually damp climate doesn’t suit my tastes. Neither does the city’s comfortably hip vibe. It is, I incline to think, a place rather too pleased with itself for its own good–but, then, it has much to be pleased about, above all its near-unrivaled natural beauty. I never get tired of looking at San Francisco. And a city that can boast of a museum like the de Young (though the building is better than the collection it houses) or an orchestra like Michael Tilson Thomas’ San Francisco Symphony needn’t apologize to anybody about anything, culturally speaking.

(First of three parts)