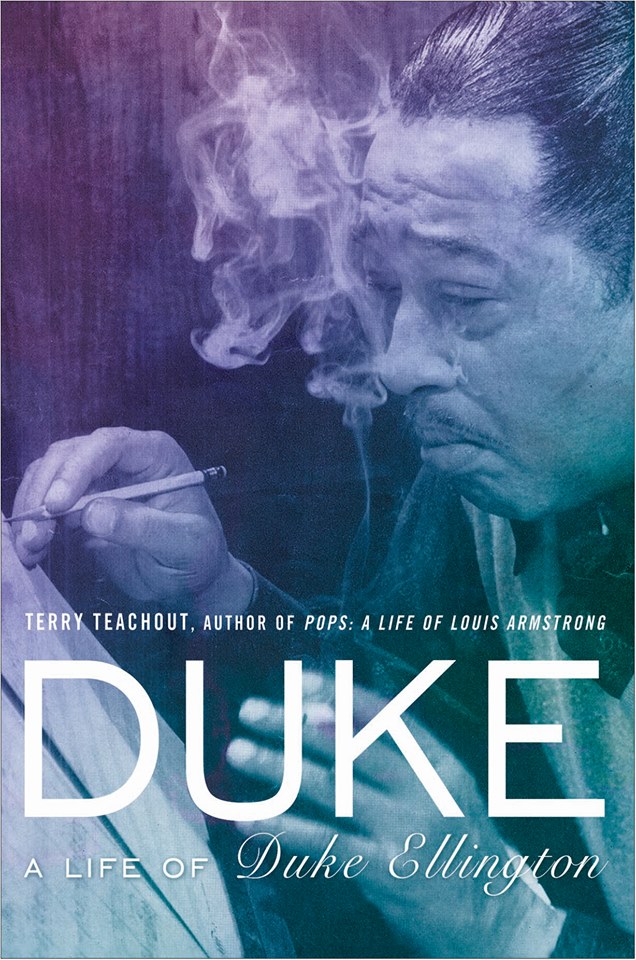

Emily Wunderlich of Gotham Books just sent me the final version of the front cover of Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. I posted an earlier version a couple of months ago, but the new image is the real thing: Duke will look like this when you see it in bookstores in October.

Emily Wunderlich of Gotham Books just sent me the final version of the front cover of Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. I posted an earlier version a couple of months ago, but the new image is the real thing: Duke will look like this when you see it in bookstores in October.

It was Steven Lasker, the great Ellington scholar-collector, who first showed me this rarely reproduced image and suggested that it would make an ideal cover for Duke, not only because it’s so visually striking but because it shows the scar on Ellington’s left cheek more clearly than any other photograph I know. Ellington acquired that scar in 1929, not long before he made his sound-film debut in Black and Tan, and in Duke I explain how he got it.

Here’s the story, straight from the as-yet-unpublished pages of Duke. It is, if I do say so myself, quite a tale.

* * *

Black and Tan marked–literally–a transition in Ellington’s private life. From 1929 on his left cheek bore a prominent crescent-shaped scar that is easily visible in the film’s last scene (and in the photograph reproduced on the cover of this book). Though rarely mentioned by journalists, it made fans curious enough that he felt obliged to “explain” its presence in Music Is My Mistress, his autobiography:

I have four stories about it, and it depends on which you like the best. One is a taxicab accident; another is that I slipped and fell on a broken bottle; then there is a jealous woman; and last is Old Heidelberg, where they used to stand toe to toe with a saber in each hand, and slash away. The first man to step back lost the contest, no matter how many times he’d sliced the other. Take your pick.

None of Ellington’s friends and colleagues was in doubt about which one to pick. In Irving Mills’s words, “Women was one of the highlights in his life. He had to have women….He always had a woman, always kept a woman here, kept a woman there, always had somebody.” Most men who treat women that way are destined to suffer at their hands sooner or later, if not necessarily in so sensational a fashion as Ellington, whose wife attacked him with a razor when she found out that he was sleeping with another woman.

Who was she? All signs point to Fredi Washington. The costar of Black and Tan had launched her theatrical career in 1922 as a dancer in the chorus of the original production of Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along. Sonny Greer later described her as “the most beautiful woman” he had ever seen. “She had gorgeous skin, perfect features, green eyes, and a great figure. When she smiled, that was it!” Washington was light enough to pass for white but adamantly refused to do so, a decision that made it impossible for her to establish herself in Hollywood, though she appeared with Paul Robeson in Dudley Murphy’s 1933 film of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (for which her skin was darkened with makeup) and starred in Imitation of Life, a 1934 tearjerker in which she played, with mortifying predictability, a light-skinned black who passed for white.

Who was she? All signs point to Fredi Washington. The costar of Black and Tan had launched her theatrical career in 1922 as a dancer in the chorus of the original production of Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along. Sonny Greer later described her as “the most beautiful woman” he had ever seen. “She had gorgeous skin, perfect features, green eyes, and a great figure. When she smiled, that was it!” Washington was light enough to pass for white but adamantly refused to do so, a decision that made it impossible for her to establish herself in Hollywood, though she appeared with Paul Robeson in Dudley Murphy’s 1933 film of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones (for which her skin was darkened with makeup) and starred in Imitation of Life, a 1934 tearjerker in which she played, with mortifying predictability, a light-skinned black who passed for white.

Ellington never spoke on the record about their romantic involvement, but Washington later admitted to the film historian Donald Bogle that she and Ellington had been lovers: “I just had to accept that he wasn’t going to marry me. But I wasn’t going to be his mistress.” Their relationship was widely known at the time in the entertainment world, enough so that Mercer Ellington could write in his 1979 memoir of “a torrid love affair Pop had with a very talented and beautiful woman, an actress. I think this was a genuine romance, that there was love on both sides, and that it amounted to one of the most serious relationships of his life.”

Edna, Ellington’s wife, was no more forthcoming than Duke, saying only that she was “hurt, bad hurt when the breakup came” and referring to the affair in an interview published in Ebony in 1959 with an obliqueness worthy of her wayward husband: “Ellington thought I should have been more understanding of him….Any young girl who plans to marry a man in public life–a man who belongs to the public–should try to understand as much about the demands of show business first and not be like I was.” In point of fact, though, her lack of “understanding” extended to slashing her husband’s face. That she did so is certain, but nothing else is definitely known about the assault. “Something happened between [Ellington] and his wife and he’s been terrible with women ever since,” Lawrence Brown said. “I mean, like he’s always trying to make somebody’s wife, because somebody made his wife and they got in such a fight, that slash he has on the side of his face, she cut him while he was sleeping, with a razor.”

Edna, Ellington’s wife, was no more forthcoming than Duke, saying only that she was “hurt, bad hurt when the breakup came” and referring to the affair in an interview published in Ebony in 1959 with an obliqueness worthy of her wayward husband: “Ellington thought I should have been more understanding of him….Any young girl who plans to marry a man in public life–a man who belongs to the public–should try to understand as much about the demands of show business first and not be like I was.” In point of fact, though, her lack of “understanding” extended to slashing her husband’s face. That she did so is certain, but nothing else is definitely known about the assault. “Something happened between [Ellington] and his wife and he’s been terrible with women ever since,” Lawrence Brown said. “I mean, like he’s always trying to make somebody’s wife, because somebody made his wife and they got in such a fight, that slash he has on the side of his face, she cut him while he was sleeping, with a razor.”

Brown was a presumptively biased witness, since he later married Fredi, becoming one of a number of Ellington sidemen (five, Mercer claimed) who took up with their boss’s ex-girlfriends at one time or another. But Barney Bigard also testified that the Ellingtons were mutually unfaithful, describing Edna’s boyfriend as “quite a figure in the music world.” Regarding the act itself, an unnamed “close friend” of Ellington told a biographer that Edna had vowed to “spoil those pretty looks” before cutting him, a secondhand account that is obviously unverifiable but nonetheless sounds believable….