Nowadays I review so many plays and musicals, both in New York and elsewhere, that it’s growing more and more difficult for me to find the time to attend live performances of any other kind. Mrs. T, who loves music as much as I do but prefers to hear it in person, frequently expresses wistful regret at this state of affairs, so I decided to take her to the opera–and not just any opera, either, but the Metropolitan Opera’s revival of John Dexter’s 1977 production of Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites.

Nowadays I review so many plays and musicals, both in New York and elsewhere, that it’s growing more and more difficult for me to find the time to attend live performances of any other kind. Mrs. T, who loves music as much as I do but prefers to hear it in person, frequently expresses wistful regret at this state of affairs, so I decided to take her to the opera–and not just any opera, either, but the Metropolitan Opera’s revival of John Dexter’s 1977 production of Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites.

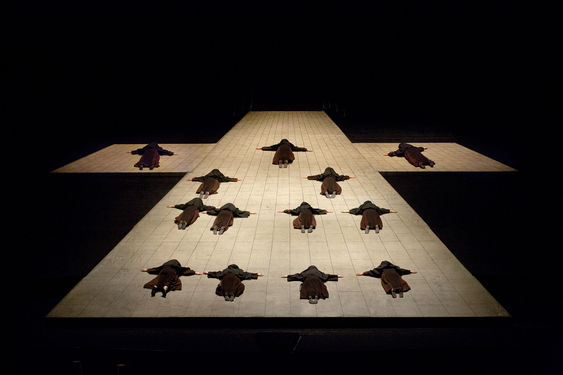

Dexter’s Dialogues is one of the greatest stage productions of any kind, operatic or otherwise, that I’ve had the good fortune to see in my entire theatergoing life. Mrs. T saw it once, a quarter-century ago. (This was the performance that she saw.) I’ve seen it twice, most recently in 2002. When I suggested that we go again, she squealed with delight.

I blush to admit that the last time I went to the Met–or, indeed, to any performance of an opera not written by me–was in 2009, when I saw Puccini’s Trittico. One of the stars of that production was Patricia Racette, the soprano who created the role of Leslie Crosbie in The Letter, my first operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec. Pat, as it happens, is also in the Met’s revival of Dlalogues. When I saw the opera there in 2002, she played Blanche, a young woman from an aristocratic family who joins a Carmelite convent whose nuns are guillotined at the height of the French Revolution. This time around she played Madame Lidoine, the convent’s newly elected prioress.

Pat was born in 1965, nine years after me. I saw her perform for the first time in 1998, when she replaced Renée Fleming (who in turn had replaced Angela Gheorghiu) in Franco Zeffirelli’s then-new Met production of La Traviata. I reviewed that performance for the New York Daily News, and flung my hat as far into the air as I could:

Pat was born in 1965, nine years after me. I saw her perform for the first time in 1998, when she replaced Renée Fleming (who in turn had replaced Angela Gheorghiu) in Franco Zeffirelli’s then-new Met production of La Traviata. I reviewed that performance for the New York Daily News, and flung my hat as far into the air as I could:

Racette is no airheaded coloratura canary, but an outstandingly gifted singing actress who uses her bright, vibrant voice as an instrument of high drama. She caught the hectic desperation just below the surface of the forced gaiety of “Sempre libera,” and moved boldly from the black despair of “Addio del passato” to the heart-tearing false hope of the death scene. The wild cheering at evening’s end was fully deserved: Rarely has an American soprano made so much of so great an opportunity.

While I have a reasonably active imagination, it never occurred to me that night that I would write an opera of my own for Pat eleven years later. Even then I was more than old enough to know that life is full of surprises, but that particular surprise was far beyond my power to conceive.

Now that I have two opera libretti under my belt and a third one in the works, it seemed appropriate to be sitting again in the Metropolitan Opera House, watching Pat assume a new, more mature role in Dialogues. To be sure, it was also sobering–a reminder of my own advancing age–but I don’t think it’s such a bad thing to be forced on occasion to reflect on such matters. No, I’m not as young as I used to be, but I’m still kicking, and the surprises, at least so far, keep on coming.

As for Dialogues of the Carmelites, I find the Met’s production to be as moving today as I did in 1994 and 2002. In 2004 I saw yet another production, this one by the New York City Opera, and blogged about it no less enthusiastically. Nine years later the opera itself means even more to me, if possible, just as Poulenc’s music continues to grow closer to my heart. I wrote about him in The Wall Street Journal a few months ago, and what I said then still goes:

Poulenc himself aspired to being nothing more than (as he put it) “an almost great composer.” What he ended up being was France’s last indisputably major classical composer, a full-fledged master who was capable of effortlessly expressing the full range of human emotion without lapsing into empty grandiloquence. If that doesn’t make him great, then the word means nothing.

What I love best about his music is the way in which, like so many other French masters, it says serious things in a seemingly light way. Dialogues is like that. It is, of course, deadly serious, but the score is never heavy in tone, not even at the very end. Here as always, Poulenc says what he has to say with elegance and lucidity, and his grave reflections on a horrific tragedy are all the more touching for it.

What I love best about his music is the way in which, like so many other French masters, it says serious things in a seemingly light way. Dialogues is like that. It is, of course, deadly serious, but the score is never heavy in tone, not even at the very end. Here as always, Poulenc says what he has to say with elegance and lucidity, and his grave reflections on a horrific tragedy are all the more touching for it.

It amused me, by the way, to note that the Met performed Götterdämmerung earlier that same day. Whatever you may think of the music of Richard Wagner, I somehow doubt that the words “light,” “elegance,” or “lucidity” are likely to figure prominently in your thoughts. Wagner is, I know, a greater master than Poulenc, but I don’t think that matters in the least. It is Poulenc who speaks most powerfully to me, and I’m glad that it was Poulenc who welcomed Mrs. T and me back to the Met after too long an absence.

* * *

The finale of John Dexter’s Metropolitan Opera production of Dialogues of the Carmelites, telecast on PBS in 1987. The role of Blanche is sung by Maria Ewing: