I’ve been so busy of late that I nearly missed Inventing Abstraction, 1901-1925, the Museum of Modern Art’s current blockbuster, which closes next Monday. One of my editors at The Wall Street Journal urged me the other day to shoehorn it into my schedule, assuring me that the wall of paintings by Kazimir Malevich was good enough all by itself to justify a visit to MoMA, a museum for which I haven’t much cared ever since it reopened in 2004.

I’ve been so busy of late that I nearly missed Inventing Abstraction, 1901-1925, the Museum of Modern Art’s current blockbuster, which closes next Monday. One of my editors at The Wall Street Journal urged me the other day to shoehorn it into my schedule, assuring me that the wall of paintings by Kazimir Malevich was good enough all by itself to justify a visit to MoMA, a museum for which I haven’t much cared ever since it reopened in 2004.

I did so on Friday, and sent my editor this note the next morning.

* * *

Here’s what I thought, in a nutshell:

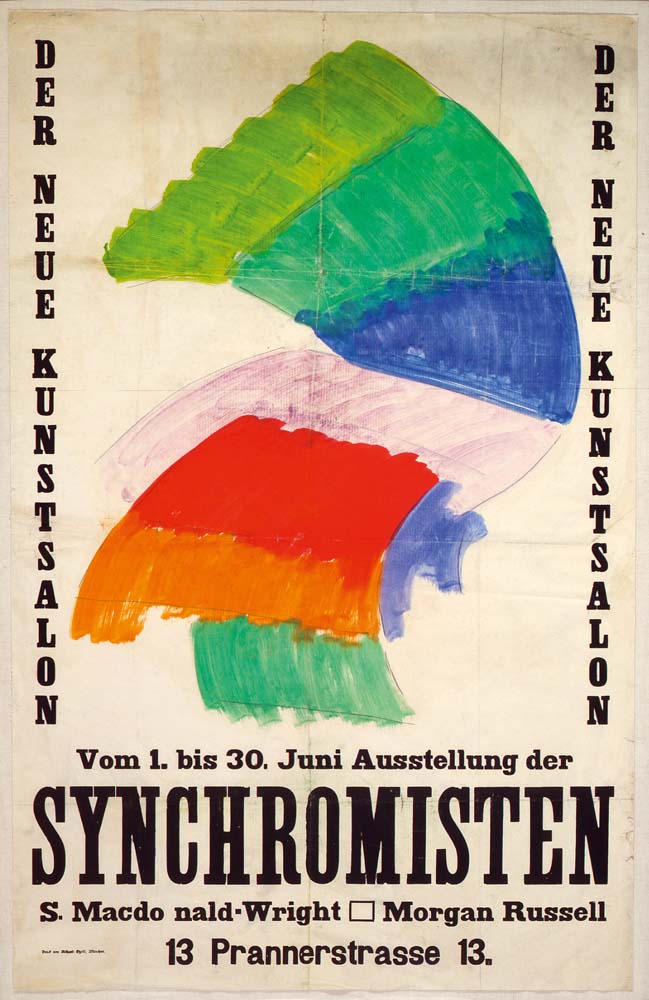

• MoMA has always been provincial about pre-1945 American modernism, and “Inventing Abstraction” (surprise, surprise!) is no exception to the rule. I was astonished to see that Arthur Dove, who can lay a serious claim to having invented abstraction, was fobbed off with two paintings tucked away in a corner–though I do give the curator full credit for devoting an appropriate amount of space to Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, and Morton Schamberg. That corner installation was one of the best parts of the show.

• MoMA has always been provincial about pre-1945 American modernism, and “Inventing Abstraction” (surprise, surprise!) is no exception to the rule. I was astonished to see that Arthur Dove, who can lay a serious claim to having invented abstraction, was fobbed off with two paintings tucked away in a corner–though I do give the curator full credit for devoting an appropriate amount of space to Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, and Morton Schamberg. That corner installation was one of the best parts of the show.

• Speaking of provincial, I couldn’t believe that two entire walls were devoted to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Yawn, and then some. Will we never be rid of the snobby blight of the Bloomsberries?

• Speaking of provincial, I couldn’t believe that two entire walls were devoted to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Yawn, and then some. Will we never be rid of the snobby blight of the Bloomsberries?

• One of the many things triumphantly demonstrated by “Inventing Abstraction” is the sheer volume of second- and third-rate art (see above) that was generated by the rise of the abstractionists. The imitability of so many key figures of the movement never ceases to fascinate me. I’m not sure, though, that I fully understood until now how quickly abstraction evolved into an “academic” style.

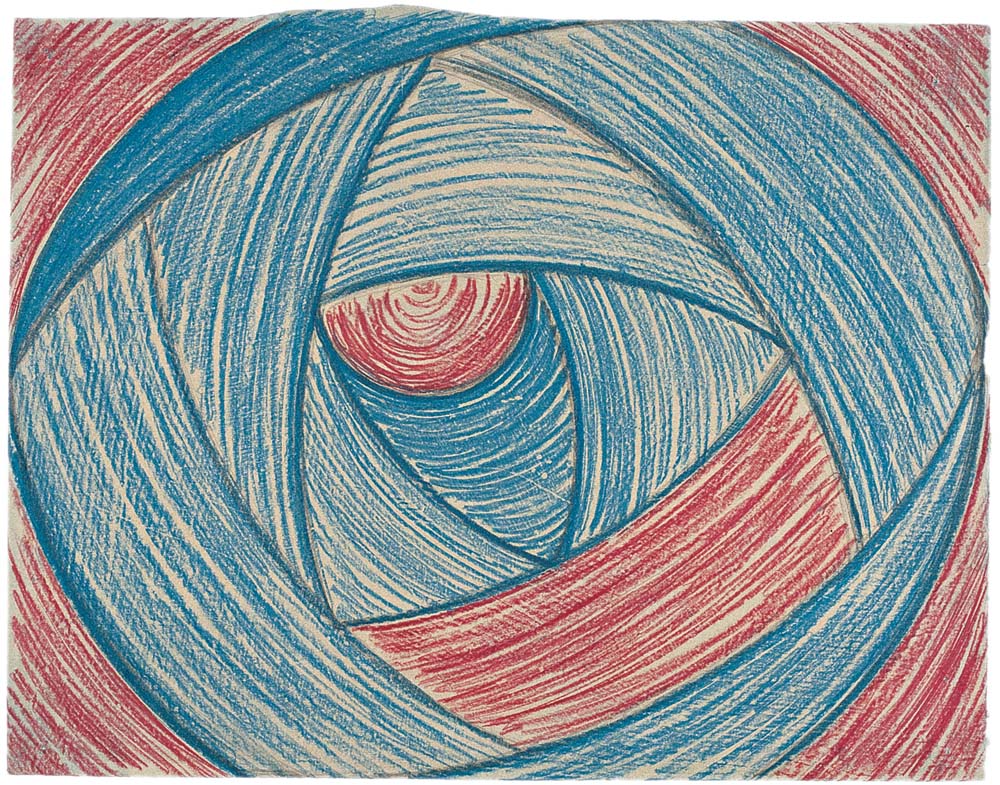

• I knew, of course, that Vaslav Nijinsky had done drawings that were directly related to his dances, but I’d never seen any of them other than in black-and-white reproductions. No, they’re not especially accomplished or original, but they certainly are interesting, just like Arnold Schoenberg’s paintings.

• I knew, of course, that Vaslav Nijinsky had done drawings that were directly related to his dances, but I’d never seen any of them other than in black-and-white reproductions. No, they’re not especially accomplished or original, but they certainly are interesting, just like Arnold Schoenberg’s paintings.

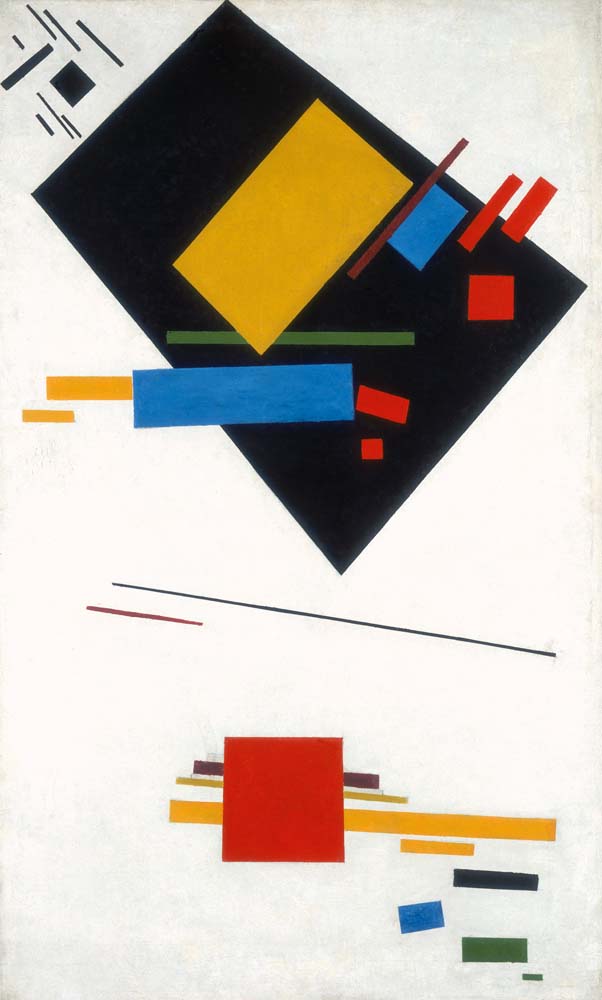

• You were absolutely right about the Malevich wall. It was like tossing a firecracker into the room–my attention was seized as soon as I turned a corner and saw all those paintings in one place. I already knew that I liked Malevich’s work, but to see so many pieces in so historically wide-ranging a context (instead of as part of an exhibition of Russian modernists) made me realize for the first time just how fine he really was, and how much was lost when Stalin dropped the guillotine on modern art in the Soviet Union.

• “Inventing Abstraction” is a terrific show if you know the territory, rather less so if you don’t. Very little effort is made to teach the viewer anything. I don’t much care for over-didactic exhibitions, but it struck me that this one was in certain ways a missed opportunity.

• For what it’s worth, Augusto Giacometti’s “Chromatic Fantasy” was the painting that attracted the most foot traffic on Friday afternoon. Lots of people lingered in front of it, and many of them were vocal in their enthusiasm. I wonder if they thought it was by the other Giacometti?

• For what it’s worth, Augusto Giacometti’s “Chromatic Fantasy” was the painting that attracted the most foot traffic on Friday afternoon. Lots of people lingered in front of it, and many of them were vocal in their enthusiasm. I wonder if they thought it was by the other Giacometti?

• The chorale from Charles Ives’ Three Quarter-Tone Pieces was playing when I poked my head into the music room. I can’t think of a more immediately or radically disorienting piece of music. It was an excellent choice, though I’m not quite sure what it has to do with the emergence of abstraction.

* * *

“Chorale,” from Charles Ives’ Three Quarter-Tone Pieces, performed by Anthony and Joseph Paratore:

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog