Paul Moravec, my operatic collaborator, has started to compose the music for The King’s Man, our third opera, which will be workshopped this October by Kentucky Opera. I finished writing the libretto late in February, but Paul was busy with another commission and wasn’t able to get going on The King’s Man until last week.

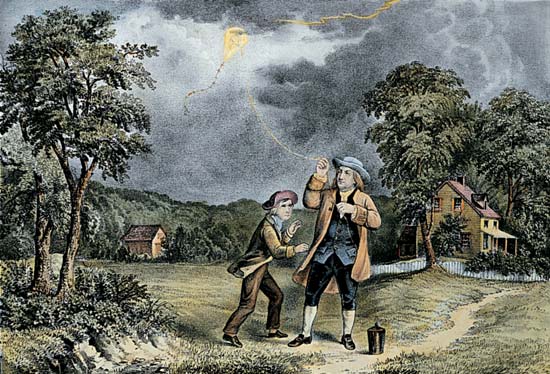

The King’s Man portrays the stormy relationship between Benjamin Franklin and his illegitimate son William, who were on opposite sides in the American Revolutionary War. Operas are rarely composed in sequence, and Paul decided to start by writing the arietta in which Ben (as Paul and I refer to Franklin in conversation) attempts to explain to his disapproving son why he has a Puritan streak in his character that is sharply at odds with his worldliness:

The King’s Man portrays the stormy relationship between Benjamin Franklin and his illegitimate son William, who were on opposite sides in the American Revolutionary War. Operas are rarely composed in sequence, and Paul decided to start by writing the arietta in which Ben (as Paul and I refer to Franklin in conversation) attempts to explain to his disapproving son why he has a Puritan streak in his character that is sharply at odds with his worldliness:

I was born on a Sunday

In the angry shadow of God,

Baptized on the day of my birth

Into a gray, Puritan life

To save me from the fires of hell.

They believed that a child born on a Sunday

Must be a child of Satan.

This was my youth,

From the Puritans of Boston

To the Quakers of Philadelphia:

From same to same,

Gray to gray,

Hard work, cold baths,

Hatred of the joys of the flesh.

(Furious) Damn it all!

God damn it all!

No God of love

Would make such a place,

Cold as ice,

Sharp as a knife,

No joy…

No life.

I sometimes imagine a “dummy” musical background when I write the words for an operatic scene, but I didn’t do that this time around. Hence it came as a delicious shock when Paul e-mailed me a sound file of the first compositional draft of “I was born on a Sunday.” He trimmed a few lines of my original draft, which was a bit wordy, then transformed the rest of it into a darkly chromatic minor-key episode (it runs for a minute and a half) whose rhythms are sharp and nervous in a way that I never foresaw.

It’s been a couple of years since I last heard my words freshly set to music, and I’d forgotten how startling an experience it is. Even if, like me, you’re a trained musician who has dabbled in composition, you simply can’t imagine how it feels when music–especially the music of a major composer like Paul–is added to something that you’ve written. It’s more than just a matter of superimposing a layer of color, in the way that a black-and-white film can be electronically “colorized” after the fact. What is added is meaning.

It’s been a couple of years since I last heard my words freshly set to music, and I’d forgotten how startling an experience it is. Even if, like me, you’re a trained musician who has dabbled in composition, you simply can’t imagine how it feels when music–especially the music of a major composer like Paul–is added to something that you’ve written. It’s more than just a matter of superimposing a layer of color, in the way that a black-and-white film can be electronically “colorized” after the fact. What is added is meaning.

The results reminded me yet again that the libretto of an opera is at bottom nothing more than an enabling condition that makes the musical score possible. Of course a libretto has to be dramatically compelling, and if possible it should be memorable in its own right. In the end, though, the only thing that really matters about the words of an opera is what the composer does with them. So far, I like what Paul is doing to my libretto for The King’s Man–a lot.