As of today, here’s how things stand with Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington:

• A pair of top-tier Ellington scholars, Steven Lasker and Brian Priestley, separately proofread and fact-checked the manuscript of Duke sentence by sentence and came back to me with long lists of corrections, queries, and suggested fixes. I bless their names.

• I had my first face-to-face meeting with Gotham’s publicity team two weeks ago. They’re already lining up the various out-of-town appearances–lectures, signings, radio, TV–that will begin shortly after Duke is published on October 17.

• Amazon made Duke available for pre-ordering on its website last week.

• I’ve found high-quality copies of all but three of the thirty-five “images” that will be interspersed throughout the book. I’m hoping to lock up those three strays by the beginning of next week.

• I’ve found high-quality copies of all but three of the thirty-five “images” that will be interspersed throughout the book. I’m hoping to lock up those three strays by the beginning of next week.

• I expect to receive the copyedited manuscript from Gotham Books sometime today or tomorrow. At that point, I’ll start inserting various changes that I’ve made since handing in the book on February 1. Most are small, but I did uncover a modest amount of new information about Ellington that has turned up in the past couple of months. It’s not too late to put it in the book, so I will.

• I’ve approved the design for the cover of the book, which I’ll be posting as soon as we receive permission to use the photograph that will (I hope!) appear on the back cover. Gotham will be e-mailing me sample pages of the interior typographical design later today or tomorrow. At my request, the text of Duke will be composed in Galliard, my favorite typeface.

• I’ll return the copyedited manuscript to Gotham on April 22. Shortly after that, Gotham will send me typeset “page proofs” to correct, plus the “flap copy” that will appear on the dust jacket. (It’ll be based on the catalog copy for Duke, which I approved back in December.)

Once I’ve finished with the page proofs, I’m finished with Duke. All that’ll be left to do is wait.

In the meantime, I want to share with you the book’s two epigraphs. The first is from Somerset Maugham’s Don Fernando: “There is one very good thing to be said of posterity, and this is that it turns a blind eye on the defects of greatness.”

The second is a line from “We Wear The Mask,” Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1895 poem about the lives of blacks in America: We wear the mask that grins and lies.

Between them, I think these two epigraphs suggest much about the life, work, and personality of the enigma who was Duke Ellington.

Archives for April 2013

TT: Snapshot

Peter Pears and Julian Bream perform lute songs by Dowland and Rosseter:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“A burglar who respects his art always takes his time before taking anything else.”

O. Henry, “Makes the Whole World Kin”

TT: Getting out more

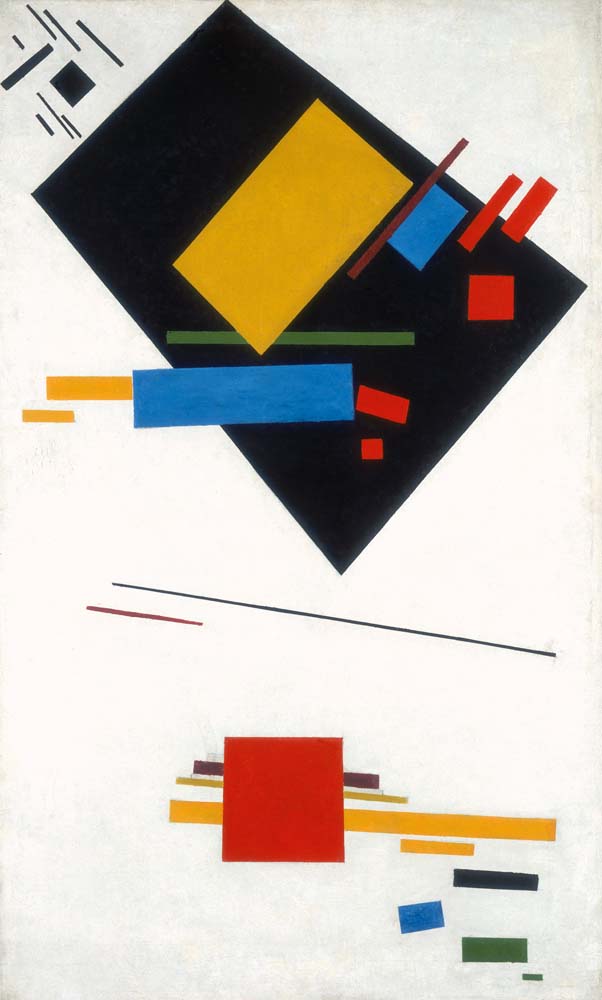

I’ve been so busy of late that I nearly missed Inventing Abstraction, 1901-1925, the Museum of Modern Art’s current blockbuster, which closes next Monday. One of my editors at The Wall Street Journal urged me the other day to shoehorn it into my schedule, assuring me that the wall of paintings by Kazimir Malevich was good enough all by itself to justify a visit to MoMA, a museum for which I haven’t much cared ever since it reopened in 2004.

I’ve been so busy of late that I nearly missed Inventing Abstraction, 1901-1925, the Museum of Modern Art’s current blockbuster, which closes next Monday. One of my editors at The Wall Street Journal urged me the other day to shoehorn it into my schedule, assuring me that the wall of paintings by Kazimir Malevich was good enough all by itself to justify a visit to MoMA, a museum for which I haven’t much cared ever since it reopened in 2004.

I did so on Friday, and sent my editor this note the next morning.

* * *

Here’s what I thought, in a nutshell:

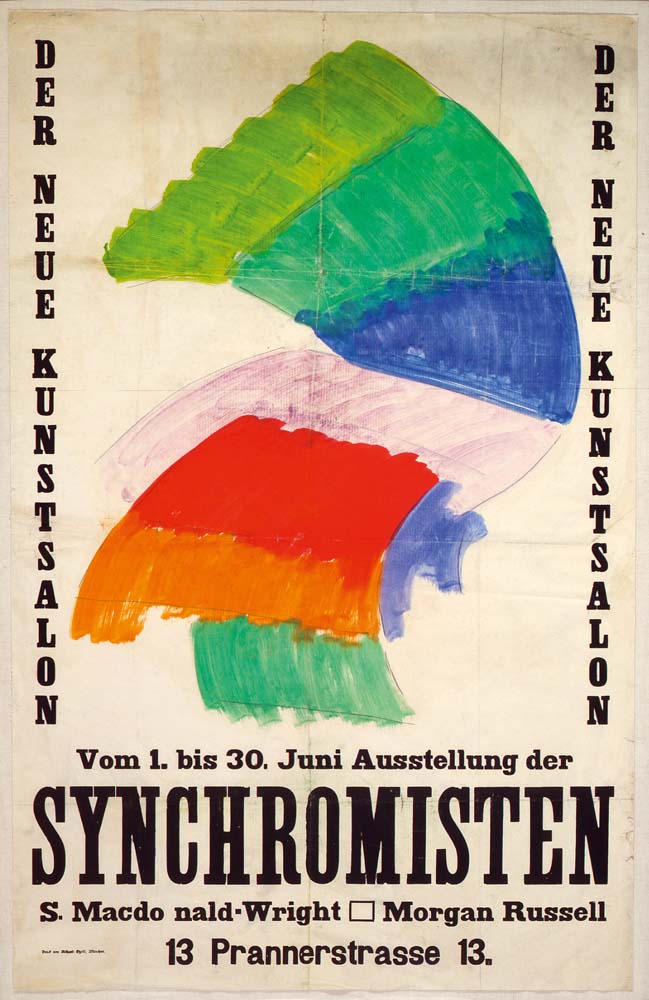

• MoMA has always been provincial about pre-1945 American modernism, and “Inventing Abstraction” (surprise, surprise!) is no exception to the rule. I was astonished to see that Arthur Dove, who can lay a serious claim to having invented abstraction, was fobbed off with two paintings tucked away in a corner–though I do give the curator full credit for devoting an appropriate amount of space to Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, and Morton Schamberg. That corner installation was one of the best parts of the show.

• MoMA has always been provincial about pre-1945 American modernism, and “Inventing Abstraction” (surprise, surprise!) is no exception to the rule. I was astonished to see that Arthur Dove, who can lay a serious claim to having invented abstraction, was fobbed off with two paintings tucked away in a corner–though I do give the curator full credit for devoting an appropriate amount of space to Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Morgan Russell, and Morton Schamberg. That corner installation was one of the best parts of the show.

• Speaking of provincial, I couldn’t believe that two entire walls were devoted to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Yawn, and then some. Will we never be rid of the snobby blight of the Bloomsberries?

• Speaking of provincial, I couldn’t believe that two entire walls were devoted to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Yawn, and then some. Will we never be rid of the snobby blight of the Bloomsberries?

• One of the many things triumphantly demonstrated by “Inventing Abstraction” is the sheer volume of second- and third-rate art (see above) that was generated by the rise of the abstractionists. The imitability of so many key figures of the movement never ceases to fascinate me. I’m not sure, though, that I fully understood until now how quickly abstraction evolved into an “academic” style.

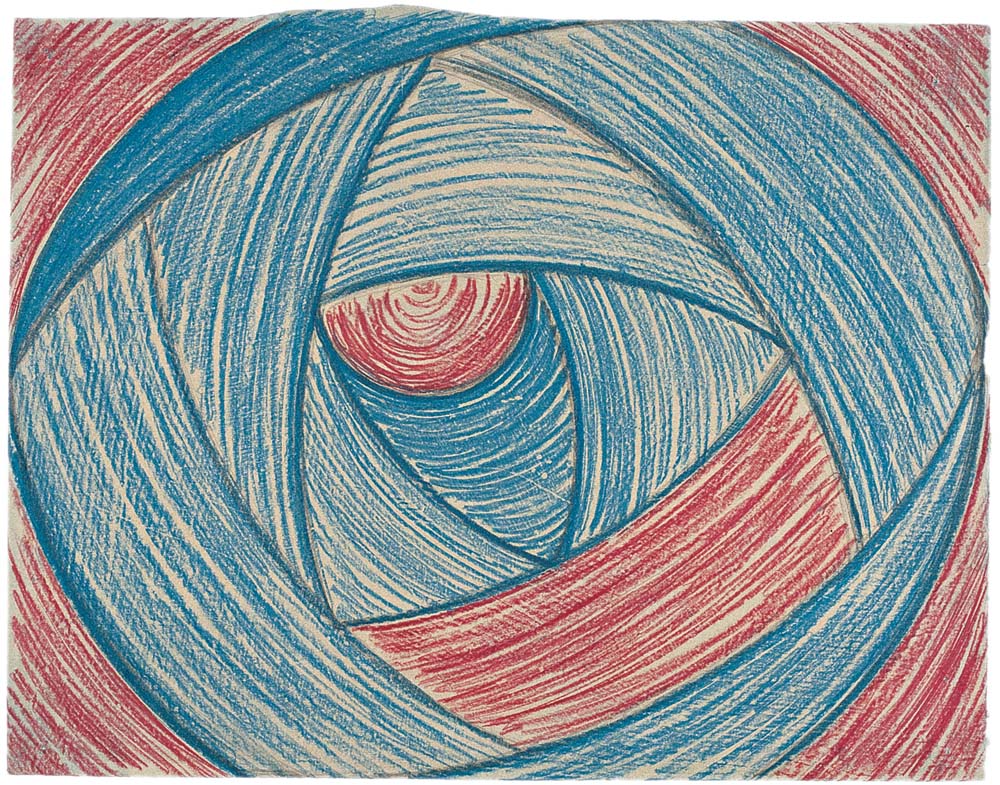

• I knew, of course, that Vaslav Nijinsky had done drawings that were directly related to his dances, but I’d never seen any of them other than in black-and-white reproductions. No, they’re not especially accomplished or original, but they certainly are interesting, just like Arnold Schoenberg’s paintings.

• I knew, of course, that Vaslav Nijinsky had done drawings that were directly related to his dances, but I’d never seen any of them other than in black-and-white reproductions. No, they’re not especially accomplished or original, but they certainly are interesting, just like Arnold Schoenberg’s paintings.

• You were absolutely right about the Malevich wall. It was like tossing a firecracker into the room–my attention was seized as soon as I turned a corner and saw all those paintings in one place. I already knew that I liked Malevich’s work, but to see so many pieces in so historically wide-ranging a context (instead of as part of an exhibition of Russian modernists) made me realize for the first time just how fine he really was, and how much was lost when Stalin dropped the guillotine on modern art in the Soviet Union.

• “Inventing Abstraction” is a terrific show if you know the territory, rather less so if you don’t. Very little effort is made to teach the viewer anything. I don’t much care for over-didactic exhibitions, but it struck me that this one was in certain ways a missed opportunity.

• For what it’s worth, Augusto Giacometti’s “Chromatic Fantasy” was the painting that attracted the most foot traffic on Friday afternoon. Lots of people lingered in front of it, and many of them were vocal in their enthusiasm. I wonder if they thought it was by the other Giacometti?

• For what it’s worth, Augusto Giacometti’s “Chromatic Fantasy” was the painting that attracted the most foot traffic on Friday afternoon. Lots of people lingered in front of it, and many of them were vocal in their enthusiasm. I wonder if they thought it was by the other Giacometti?

• The chorale from Charles Ives’ Three Quarter-Tone Pieces was playing when I poked my head into the music room. I can’t think of a more immediately or radically disorienting piece of music. It was an excellent choice, though I’m not quite sure what it has to do with the emergence of abstraction.

* * *

“Chorale,” from Charles Ives’ Three Quarter-Tone Pieces, performed by Anthony and Joseph Paratore:

TT: Almanac

“A story with a moral appended is like the bill of a mosquito. It bores you, and then injects a stinging drop to irritate your conscience.”

O. Henry, “The Gold that Glittered”

TT: Cleaning up nicely

The last time I had my picture taken at my own request was in 2009. I was sorely in need of a new publicity photo, and Ken Howard, who was shooting the Santa Fe Opera that summer, photographed me in the auditorium, wearing my brand-new curtain-call suit and a vintage Givenchy tie given to me by Mrs. T that had once belonged to Virgil Thomson. I still use Ken’s excellent head shot–it will appear on the dust jacket of Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington–and I doubt that I’ll have another one taken any time soon, at least not until advancing age transforms me so radically that I feel obliged to keep up with my real-life face.

The last time I had my picture taken at my own request was in 2009. I was sorely in need of a new publicity photo, and Ken Howard, who was shooting the Santa Fe Opera that summer, photographed me in the auditorium, wearing my brand-new curtain-call suit and a vintage Givenchy tie given to me by Mrs. T that had once belonged to Virgil Thomson. I still use Ken’s excellent head shot–it will appear on the dust jacket of Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington–and I doubt that I’ll have another one taken any time soon, at least not until advancing age transforms me so radically that I feel obliged to keep up with my real-life face.

My “session” with Ken came to mind when I read in The Wall Street Journal that Sears and Wal-Mart had shut down their in-store portrait studios:

The photographer that ran the portrait studios at Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Sears Holdings Corp.and Babies “R” Us has abruptly shuttered its business, ending a long-time retail tradition–at least for now–at those stores.

CPI Corp., in a statement on its website, said it has closed all of its U.S. studios “after many years of providing family portrait photography.” The St. Louis-based company didn’t explain the hasty closure, and calls to CPI went unanswered. However, the company has struggled financially, hurt by the rise of digital photography….

Department stores have long offered portrait services at their stores. The studios are a place where family milestones can be captured, like a youngster’s birthday or a holiday picture. The studios also would bring in customers that could fan out and shop in other parts of the store.

Ann Althouse, who also took note of this story, thinks that it marks a cultural turning point: “We all already know what everyone looks like. The ponderous, formal recording of ourselves for posterity isn’t a notion capable of ever crossing our minds again. It will be snapshots on the fly from here on out.” I have no doubt that she’s right. Not only is ours a DIY culture, but postmodern Americans reflexively eschew any kind of formality save under the direst and most official of circumstances. Nor am I all that different from my determinedly casual-looking juniors. Nowadays my four suits mostly go unworn, and I can’t remember the last time that I put on a tie to see an opera or a play, save for the opening nights of the ones that I’ve written.

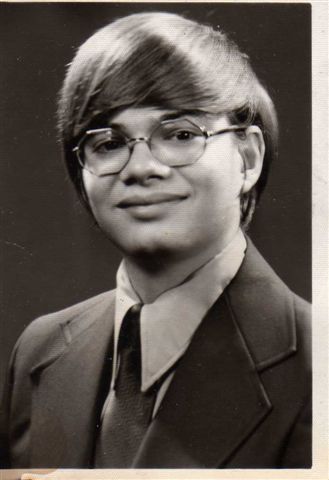

Being the sort of person that I am, you’d think that I’d get dressed up more often. I did in my younger years, never more often than when I lived in Smalltown, U.S.A. To be sure, small-town portrait photography had already tilted sharply in the direction of gooey full-color sentimentality when I graduated from high school in 1974, but I was a tradition-loving kid who had no wish to pose in front of anything other than a neutral background dressed in anything other than a suit and tie. So I decided instead to have my own senior picture taken by the Baugher Studio, which had graced Smalltown my whole life long.

Being the sort of person that I am, you’d think that I’d get dressed up more often. I did in my younger years, never more often than when I lived in Smalltown, U.S.A. To be sure, small-town portrait photography had already tilted sharply in the direction of gooey full-color sentimentality when I graduated from high school in 1974, but I was a tradition-loving kid who had no wish to pose in front of anything other than a neutral background dressed in anything other than a suit and tie. So I decided instead to have my own senior picture taken by the Baugher Studio, which had graced Smalltown my whole life long.

Loy M. Baugher, whose daughter has posted a Web page devoted to his memory, was a staunch conservative who only worked in black and white and refused to have any truck with cloying location shots. No doubt for that reason, his custom had all but dried up by 1974. The Baugher Studio, not surprisingly, went out of business a few months after I graduated, and Mr. Baugher (as everyone called him, at least in my hearing) died not long after that. Mine must have been one of the very last senior photos that he took. It’s a good one, too: I looked just like that in high school, and I don’t look all that much different thirty-nine years later.

My parents mostly relied on snapshots, but they did pose for a fair number of more-or-less formal portraits. At one time they had their portraits taken by a once-popular Chattanooga chain studio called Olan Mills that now appears to be on the verge of following Sears Portrait Studios into the memory hole of capitalism. After that they relied, if memory serves, on the photos that were shot for the annual membership directories that were published by the Smalltown church that they attended.

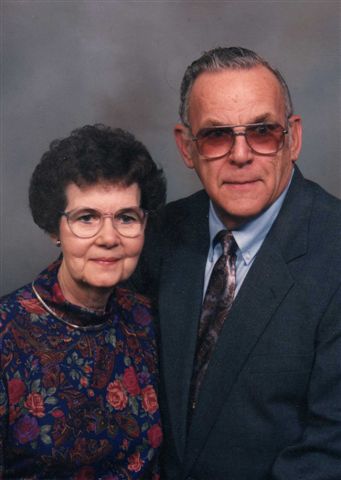

The picture on the right shows with perfect exactitude what Mom and Dad looked like when they got dressed up for a fancy occasion circa 1980. I don’t know who took it, but the unknown photographer clearly went out of his or her way to ensure that their facial expressions were animated without slopping over into smile-for-the-birdie silliness, for which much thanks.

The picture on the right shows with perfect exactitude what Mom and Dad looked like when they got dressed up for a fancy occasion circa 1980. I don’t know who took it, but the unknown photographer clearly went out of his or her way to ensure that their facial expressions were animated without slopping over into smile-for-the-birdie silliness, for which much thanks.

While I prefer to remember my parents in less studied poses, I like this one, too. Even after illness started to have its cruel way with their outward appearance, they were still a handsome couple, and it pleases me that they made a point of leaving their loving sons a permanent record of how they looked on Sunday mornings, back when the world was younger and–for better and worse–more proper.

TT: New and improved

I posted lots of new stuff in the right-hand column over the weekend. Take a peek and see if anything interests you!

TT: Just because

“This Is Your Story,” a parody of This Is Your Life performed by Sid Caesar, Howard Morris, and Carl Reiner on Your Show of Shows:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)