My brother recently sent me a copy of Life published on February 6, 1956, the day that I was born. Nowadays Life, which folded in 1972, is scarcely remembered save by senior citizens, and it was already in terminal decline when I was a boy. In 1956, though, it was still an immensely powerful publication, a tabloid-sized illustrated magazine that ran long, serious articles–it serialized The Old Man and the Sea and Winston Churchill’s war memoirs–but was mainly known for its photographs of the week’s news, which were shot by the likes of Margaret Bourke-White, Robert Capa, and Gordon Parks.

The rise of television eventually made Life obsolete, just as the coming of the internet is now doing the same thing to Time, its sister publication, but throughout the Forties and Fifties it was Life that showed Americans what the world looked like, and told them what to think about what they saw in its pages.

What did the world look like during the week I was born, midway through the Age of Eisenhower? If you go by Life, things were pretty quiet. Shirley Jones, the star of the surpassingly bland film version of Carousel, was on the cover, and the biggest “story” of the week was an excerpt from Harry Truman’s presidential memoirs, for whose serial rights the magazine had laid out a tidy sum. As for the other top-billed story, the cover line tells you all you need to know: “New Series on a Family Problem: How to Give Children’s Parties.”

As usual, the editors devoted a good-sized chunk of the magazine to a serious but safe high-culture story, a review of a traveling exhibition of paintings by Reginald Marsh, accompanied by an editorial in which readers were assured that it was still all right to like representational art: “Fortunately not all our artists run with the novelty-seeking pack. Fortunately, too, the abstractionist dogma that painting should have nothing to do with nature or humanity has not monopolized the art world.”

As is so often the case with old magazines, it’s the ads, not the stories, that turn out to be most interesting in retrospect. Some of the products, like Campbell’s Soup, remain familiar to this day. Others are long forgotten. (Does anybody still use Vitalis Hair Tonic?) All, though, are plugged straightforwardly and without a trace of wit, much less irony: “The generous Sun–Some people worship it–all children play in it–and corn soaks up more of it than any other grain. (There’s a whole summer of sun in every kernel.) Then Kellogg’s flavors, flakes and packages it, calls it Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, and gives it back to you every morning.)”

As is so often the case with old magazines, it’s the ads, not the stories, that turn out to be most interesting in retrospect. Some of the products, like Campbell’s Soup, remain familiar to this day. Others are long forgotten. (Does anybody still use Vitalis Hair Tonic?) All, though, are plugged straightforwardly and without a trace of wit, much less irony: “The generous Sun–Some people worship it–all children play in it–and corn soaks up more of it than any other grain. (There’s a whole summer of sun in every kernel.) Then Kellogg’s flavors, flakes and packages it, calls it Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, and gives it back to you every morning.)”

At first I found the sheer earnestness of the ads to be oddly touching, but I was rolling my eyes by the time I’d made it halfway through the magazine.

Contrary to its reputation, America in the Fifties was a lot more exciting than you’d guess from flipping through the pages of this particular issue of Life. Among other things, Elvis Presley sang “Baby, Let’s Play House” and “Tutti Frutti” on The Dorsey Brothers Stage Show just two days before Shirley Jones’ pretty face appeared on the cover. That particular cultural development had yet to be noticed by the editors of Life in February of 1956, but I dare say it was at least as significant as anything else that appeared in the magazine that year.

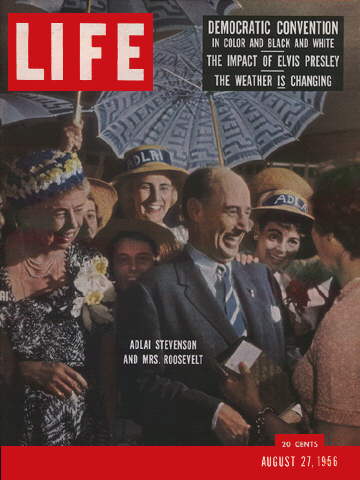

Needless to say, Life eventually caught up with Elvis, running a feature in August that took what the editors doubtless regarded as an even-handed view of his burgeoning celebrity:

Needless to say, Life eventually caught up with Elvis, running a feature in August that took what the editors doubtless regarded as an even-handed view of his burgeoning celebrity:

Up to a point the country can withstand the impact of Elvis Presley as a familiar and acceptable phenomenon. Wherever the lean, 21-year-old Tennessean goes to howl out his combination of hillbilly and rock and roll, he is beset by teenage girls yelling for him. They dote on his sideburns and pegged pants, cherish cups of water dipped from his swimming pool, covet strands of his hair, boycott disc jockeys who dislike his records (they have sold some six million copies). All this the country has seen before–with [Johnny] Ray, Sinatra and all the way back to Rudy Vallee.

But with Elvis Presley the daffiness has been deeply disturbing to civic leaders, clergymen, some parents. He does not just bounce to accent his heavy beat. He uses a bump and grind routine usually seen only in burlesque. His young audiences, unexposed to such goings-on, do not just shout their approval. They get set off by shock waves of hysteria, going into frenzies of screeching and wailing, ending up in tears….

Such was Life in the year of my birth.