“It’s easy to forget that the latter-day dominance of the small-cast play is a fairly recent development in theatrical history. Large casts used to be the rule, not the exception. Indeed, most of the best-known American plays of the 20th century called for performing forces that would now be seen by penny-pinching producers as insanely extravagant…”

Archives for March 29, 2013

TT: Hamlette, Prince of Denmark

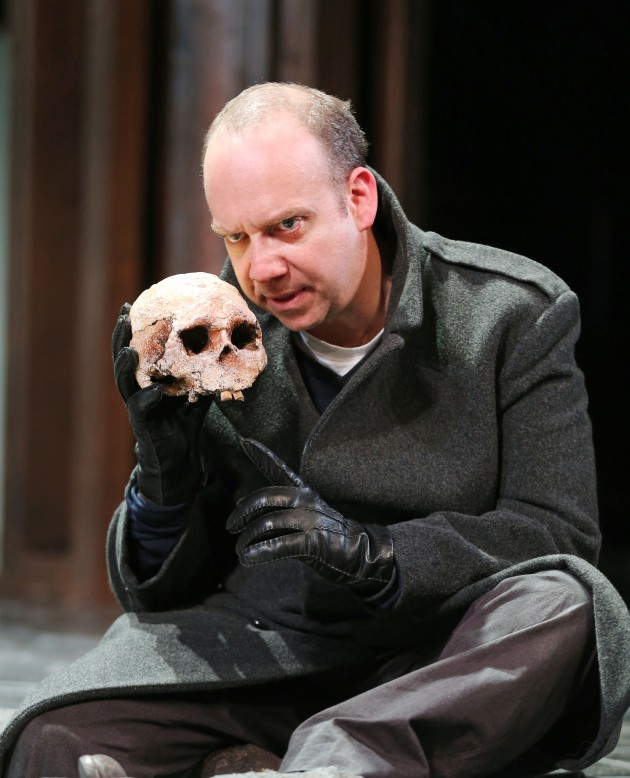

I’m reviewing two very different stagings of Hamlet in this week’s drama column. The first is Yale Rep’s modern-dress production, in which Paul Giamatti plays the title role. The second is Bedlam’s four-person off-Broadway version, starring and directed by Eric Tucker. I also have a few enthusiastic words to say about the New York transfer of Tina Packer’s Women of Will. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Paul Giamatti is everybody’s favorite semi-famous screen actor. I’ve never seen him give a lackluster performance, and his work in “American Splendor” and “Sideways” deserves to be hung in a portrait gallery of American personality types. Nobody plays maladjusted geeks better.

Paul Giamatti is everybody’s favorite semi-famous screen actor. I’ve never seen him give a lackluster performance, and his work in “American Splendor” and “Sideways” deserves to be hung in a portrait gallery of American personality types. Nobody plays maladjusted geeks better.

But…Hamlet?

What Mr. Giamatti is doing in the Yale Repertory Theatre’s production of “Hamlet” makes sense of a sort–on paper. Not only does he have extensive stage experience, but his interpretation, with its touches of manic comedy, shows every sign of being deeply considered. The problem is that Mr. Giamatti is not equipped to play a classical role like Hamlet on a proscenium stage in a medium-sized theater. He is very short and nearly bald and has a soft, edgeless voice, and though his line readings are unfailingly interesting, he has no feel for Shakespeare’s verse, which he speaks as though it were well-written prose….

If you want to see a radically unconventional “Hamlet” that makes every kind of dramatic sense, head downtown to Access Theatre. Bedlam, the four-person company which electrified Off-Broadway audiences last spring with its revival of George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan,” is now performing an equally exciting miniature rendering of Shakespeare’s longest play, performed in street clothes and acted with sublime ferocity.

To present a nearly uncut “Hamlet” with four actors in a tiny performance space may sound like a stunt. Nothing doing. It is, in fact, an experience so intense and concentrated that you’ll feel as though you were part of the action–and it moves so fast that you’ll scarcely be conscious of the play’s extraordinary length, save to notice that the traditional cuts made in virtually all stagings of “Hamlet” are not merely unnecessary but harmful to the play’s total effect….

To present a nearly uncut “Hamlet” with four actors in a tiny performance space may sound like a stunt. Nothing doing. It is, in fact, an experience so intense and concentrated that you’ll feel as though you were part of the action–and it moves so fast that you’ll scarcely be conscious of the play’s extraordinary length, save to notice that the traditional cuts made in virtually all stagings of “Hamlet” are not merely unnecessary but harmful to the play’s total effect….

Eric Tucker, the director, has cast himself as a young, vital Hamlet who feigns madness with a macabre ferocity…

Mr. Tucker’s gifts as a director are also on display in “Women of Will,” a two-person lecture-recital in which Tina Packer, brilliantly assisted by Nigel Gore, explores and analyzes how Shakespeare’s portrayals of women evolved over the course of his career. Forgive me if this bald description makes “Women of Will” sound like a classroom exercise, because it’s anything but that. To see Ms. Packer and Mr. Gore, neither of whom is young anymore, perform the balcony scene from “Romeo and Juliet” with no “scenery” but a chair is to be taught anew that great actors require no sets or props to lure you into a world of all-encompassing illusion. All they need are their bodies and souls…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A trailer for Women of Will:

TT: Filling up a stage

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss the latter-day decline and fall of the large-cast play. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What will be the most frequently produced American play of the 2013-14 season? I’m betting on David Ives’ “Venus in Fur,” a smart, serious comedy about the role of power in sexual relationships. Not only is it terrific, but “Venus in Fur” requires only two actors, making it cheap to produce. No wonder everybody wants to do it.

What will be the most frequently produced American play of the 2013-14 season? I’m betting on David Ives’ “Venus in Fur,” a smart, serious comedy about the role of power in sexual relationships. Not only is it terrific, but “Venus in Fur” requires only two actors, making it cheap to produce. No wonder everybody wants to do it.

Theater professionals know all too well that few American companies are willing to take a chance on large-cast plays nowadays. Because of the recession, regional companies have grown steadily more risk-averse, and playwrights who long to see their work performed onstage are responding accordingly by writing smaller-scaled shows….

It’s easy to forget that the latter-day dominance of the small-cast play is a fairly recent development in theatrical history. Large casts used to be the rule, not the exception. Indeed, most of the best-known American plays of the 20th century called for performing forces that would now be seen by penny-pinching producers as insanely extravagant. Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” for instance, was written for a cast of 12, while Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” requires 13 actors, eight men and five women. As for Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town,” it’s usually performed by some two dozen actors, and the original 1938 Broadway production fielded a cast of 51!

Might we have lost something by forcing contemporary playwrights to work on a smaller canvas? In recent months I’ve seen revivals of three large-cast plays originally written in the Thirties and Forties that offer a priceless reminder of how things used to be….

Might we have lost something by forcing contemporary playwrights to work on a smaller canvas? In recent months I’ve seen revivals of three large-cast plays originally written in the Thirties and Forties that offer a priceless reminder of how things used to be….

Most impressive of all was Lincoln Center Theater’s revival of Clifford Odets’ “Golden Boy,” a 19-character play about the rise and fall of an ambitious young boxer that was originally produced on Broadway in 1939. By enacting his modern tragedy on the largest possible physical scale, Odets gave near-operatic scope to what might have ended up being an over-obvious story of ambition gone astray….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Happiness is beneficial for the body, but it is grief that develops the powers of the mind.”

Marcel Proust, The Past Recaptured