“Fire up the time machine, set the controls for New Orleans in 1907 and make your way to a rickety night spot on Perdido Street that is known to the locals as Funky Butt Hall. Look closely and you might see a child in short pants peering through a crack in the wall and listening to the band inside. The child is Louis Armstrong, and the band, a combo led by a cornet player named Buddy Bolden, is playing a brand-new style of music that sounds like a cross between ragtime and the blues. Don’t call it ‘jazz,’ though, because nobody in Funky Butt Hall will know what you’re talking about…”

Archives for March 11, 2013

TT: An unrecovered memory

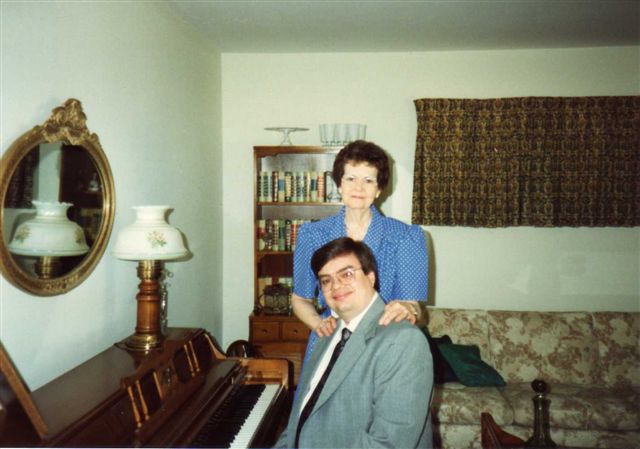

Richard Powell, my first music teacher, died eight years ago, on which occasion I wrote about what brought the two of us together:

So much of life is a matter of pure coincidence (if that’s what you think it is). I happened to see a televised concert by the Russian violinist David Oistrakh one Sunday afternoon, and the warmth and passion with which he played the Brahms D Minor Sonata, a piece I’d never heard by a composer I knew only for having written a lullaby, made a fateful impression on me. Dick Powell came to Matthews Elementary School a few months later to administer a musical aptitude test to the fifth grade, and I got a perfect score. This, he informed me the following week, qualified me to play a stringed instrument. I went home and told my astonished parents that I wanted them to buy me a violin, and that was that.

I doubt there have been many days in my life as fateful as that Sunday afternoon. I’d heard a certain amount of classical music by 1967–most of it on The Ed Sullivan Show–but my parents listened to pre-rock pop music, not Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms, and so it hadn’t occurred to me that I might play an instrument, any more than the fact that I spent most of my free time reading made me want to become a writer. That came later. It was seeing David Oistrakh that made me want to play the violin, and thus set me on the road to the life of art. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that my identity as an adult arose from that event….

I doubt there have been many days in my life as fateful as that Sunday afternoon. I’d heard a certain amount of classical music by 1967–most of it on The Ed Sullivan Show–but my parents listened to pre-rock pop music, not Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms, and so it hadn’t occurred to me that I might play an instrument, any more than the fact that I spent most of my free time reading made me want to become a writer. That came later. It was seeing David Oistrakh that made me want to play the violin, and thus set me on the road to the life of art. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that my identity as an adult arose from that event….

That, at any rate, is how I remember it, and it pleased me greatly to discover that the same telecast of the Brahms D Minor Sonata that I saw as a boy has now been posted on YouTube. It turns out that the pianist was none other than Sviatoslav Richter, and the performance, not at all surprisingly, is magnificent.

Alas, there’s a catch: I looked up the program and found, very much to my surprise, that it aired in 1970, three years after Dick Powell came to Matthews Elementary School and discovered that I was a born musician.

In other words, I really do remember seeing David Oistrakh on TV when I was young–but that wasn’t what made me want to become a musician. The proximate cause of that fateful decision is lost, presumably forever, in the thickening mists of a middle-aged man’s faulty memory.

Are you thinking what I’m thinking? This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. That oft-quoted line from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance has been wrangled over endlessly and heatedly by critics and commentators. David Thomson, for one, holds it in something close to contempt:

All of a sudden, the Ford ethos looks fossilized, yet there he is urging us to believe in the legend and call it fact. By 1962, surely it was plain to anyone that the movies had done terrible damage to a sense of American history with their addled faith in bogus myths.

I wouldn’t go nearly that far, though I do understand what Thomson is getting at. For my own part, I suggest the following amendment: When the legend becomes fact, print the legend–but if it turns out not to be true, print that, too.

* * *

David Oistrakh and Sviatoslav Richter play the Brahms D Minor Sonata at Alice Tully Hall in 1970:

TT: From “jass” to jazz

The word “jazz” first started to appear regularly in print a century ago this month. On Saturday, the weekend edition of The Wall Street Journal invited me to commemorate the anniversary. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Fire up the time machine, set the controls for New Orleans in 1907 and make your way to a rickety night spot on Perdido Street that is known to the locals as Funky Butt Hall. Look closely and you might see a child in short pants peering through a crack in the wall and listening to the band inside. The child is Louis Armstrong, and the band, a combo led by a cornet player named Buddy Bolden, is playing a brand-new style of music that sounds like a cross between ragtime and the blues.

Fire up the time machine, set the controls for New Orleans in 1907 and make your way to a rickety night spot on Perdido Street that is known to the locals as Funky Butt Hall. Look closely and you might see a child in short pants peering through a crack in the wall and listening to the band inside. The child is Louis Armstrong, and the band, a combo led by a cornet player named Buddy Bolden, is playing a brand-new style of music that sounds like a cross between ragtime and the blues.

Don’t call it “jazz,” though, because nobody in Funky Butt Hall will know what you’re talking about. They call it “ragtime.” And don’t try to tell them that it will someday be played in concert halls, because if you do, they’ll laugh you off the dance floor. Bolden’s band played background music for bumping, grinding, drinking and fighting. Nobody in New Orleans thought of it as art, and nobody would think of it that way for years to come. Well into the ’60s, there were still plenty of skeptics who continued to question the musical worth of jazz, and one of the reasons for their persistent skepticism was the fact that it had been born in honky tonks with names like Funky Butt Hall.

The word “jazz” didn’t appear in print with any frequency until March 1913, exactly a century ago. What’s more, it doesn’t seem to have had anything to do with music, nor was the word coined in New Orleans….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Just because

“The Music Box,” starring Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy and directed by James Parrott:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Mrs. Ballinger is one of the ladies who pursue Culture in bands, as though it were dangerous to meet it alone.”

Edith Wharton, “Xingu”